An interview with Professor Jason Lantzer

JMC Resident Historian Elliott Drago sat down with JMC Scholar Jason Lantzer to discuss his new book, Dwight Eisenhower and the Holocaust: A History. Dr. Lantzer is the Assistant Director of the Butler University Honors Program.

The rather large shoes of Dwight D. Eisenhower

ED: What inspired you to become an American historian?

JL: History was always my favorite subject in school—where I had wonderful teachers, starting in elementary school and continuing through high school, which nurtured that interest. But even more importantly, I had parents and my extended family who indulged that interest. Whether that meant buying me books, taking me to museums or historic sites, or letting me watch the History Channel on the only television that was hooked up to cable!

There was no doubt I would major in it when I became the first in my family to go to college. Still, until my junior year, I anticipated that I would be going to law school. But History was always there calling, and thanks to several wonderful historians at Indiana University, I made the decision to become an historian as well.

The exact moment came in a course taught by the late Irving Katz, when one morning he launched into an unprompted mini lecture on why History was the perfect discipline—it was literally a lightbulb moment for me. I knew I didn’t want to be a lawyer, I wanted to be an historian. I was very fortunate that my run of wonderful mentors continued through both of my graduate degrees.

ED: What led you to write your new book, Dwight Eisenhower and the Holocaust: A History, and what is your central thesis?

JL: Interest in the Second World War was what lured me into History when I was young. However, it wasn’t until a student needed some assistance on a project that I found a reason—and ultimately a story—to really study World War II. Butler University received a substantial gift to help undergraduates pursue research on the Holocaust. In its second year, one of my former students applied to the fund and asked me to write his letter of recommendation. He received an award but discovered that while it was going to allow him to travel to Poland to do research, there was a good deal of material he wished to look at located at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.

Inspirational spotlight

JL: I happened to be going out to Washington over our spring break, so I told him I’d look into getting him what he needed. It was there that I encountered Ike’s quote about his visit to Ohrdruf. It was one of those things I was certainly aware of, but also something that I quickly discovered no one had really investigated. We knew the quote, but it appeared that virtually no historian had bothered to ask what that might mean for how Ike saw the war or how it might have helped shape his presidency. My dissertation advisor, James Madison of Indiana University, is fond of saying that the work of historians is sometimes about digging holes to see what we can find and sometimes about filling holes where no one has thought to look before. I decided to get to work!

My central thesis is that encountering the Holocaust altered how Ike saw the war he had been waging, bringing a moral tone to what heretofore had largely been a conflict of “us vs. them.”

JL: Of course, he had seen the United States as the “good guys” and the Axis powers as the “bad guys,” but what he saw at Ohrdruf, as he put it, “beggared description.” The reality of the Holocaust put the war into an all-new perspective—it shaped how he viewed what needed to be done in a postwar Europe, the Cold War, and his presidency in both overt and less obvious ways. He would never forget it and he wanted others to bear witness moving forward.

ED: Tell us a little bit about your source base, especially your archival work and use of oral histories.

JL: In many ways, my sources start and end with Ike’s own words. Because he served in the military his entire adult life, was president, an author, and lived at a time when letter writing was a necessity, I had a voluminous correspondence and speeches at my disposal to sift through. Because many of his contemporaries were also in public service (military and government), their papers, and just as importantly, their memoirs, were valuable sources as well.

Of course, he had seen the United States as the “good guys” and the Axis powers as the “bad guys,” but what he saw at Ohrdruf, as he put it, “beggared description.” The reality of the Holocaust put the war into an all-new perspective—it shaped how he viewed what needed to be done in a postwar Europe, the Cold War, and his presidency in both overt and less obvious ways. He would never forget it and he wanted others to bear witness moving forward.

ED: Tell us a little bit about your source base, especially your archival work and use of oral histories.

JL: In many ways, my sources start and end with Ike’s own words. Because he served in the military his entire adult life, was president, an author, and lived at a time when letter writing was a necessity, I had a voluminous correspondence and speeches at my disposal to sift through. Because many of his contemporaries were also in public service (military and government), their papers, and just as importantly, their memoirs, were valuable sources as well.

And while many of these sources were easily available via libraries (including interlibrary loan), my work was also facilitated by the presidential library system, starting with the Eisenhower Library, but also the Roosevelt and Truman libraries as well.

The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum’s library and archives were a treasure trove of sources, in particular, of oral histories and letters from both liberators and survivors of the camps. Those first-person accounts were incredibly powerful. I also benefited from archives and museums (in both the United States and Germany) either hosting exhibits that I was able to visit, or sharing sources and leads via email. Beyond these primary sources were the plethora of secondary works on the war, the Holocaust, and Eisenhower.

JL: Like every historian, to use an analogy Ike might have liked, I was merely advancing the ball. Other scholars helped lead the way. None of these sources would have been enough to tell the story in and of themselves, but taken as a whole, I was able to weave the story together.

ED: What were some of the key moments from Eisenhower’s life that made him a liberator of the oppressed?

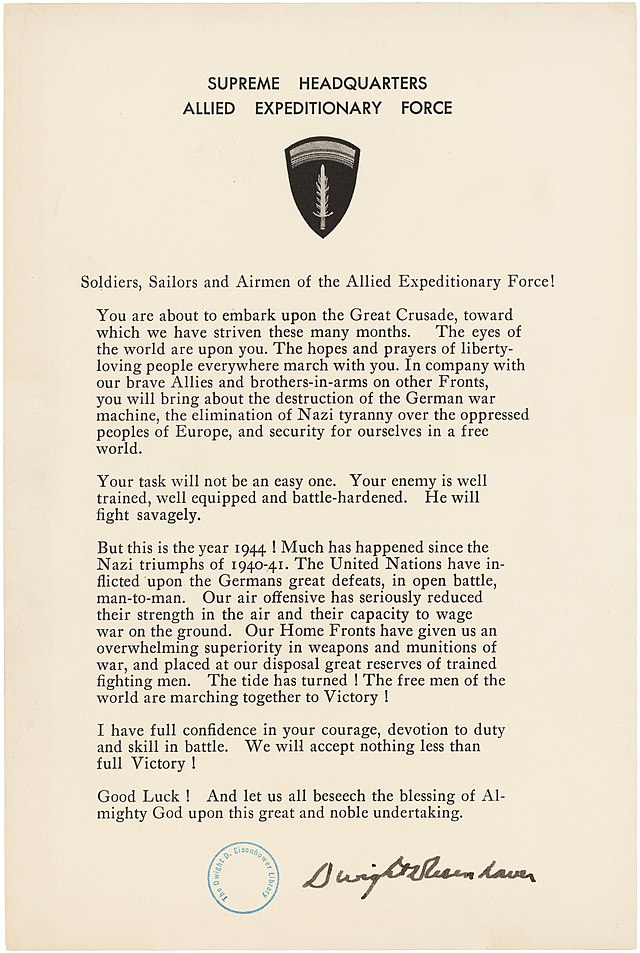

JL: Obviously, the opportunity to become a liberator was caused by the war and Ike’s role in leading the Allied forces. Even before he encountered the Holocaust at Ohrdruf, Ike spoke of what those under him were doing in terms of liberating people and nations under Nazi occupation. One need only take a look at his D-Day address to see the imagery. So, I think from December of 1941, he understood the grand scope, size, and importance of the war he was engaged in.

This sense was also likely helped by the fact that for several years prior to the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, Ike had served in the Philippines—so even though his focus was on the European Theatre of Operations, he always appreciated the global nature of the conflict. But those, in some sense, are just the proximate causes of Ike as liberator. At the core were the moral sense and values instilled in him as a child by his parents. Ike was raised to treat people with kindness and grace, to view and treat the janitor with the same respect as a prime minister, for example.

This sense was also likely helped by the fact that for several years prior to the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, Ike had served in the Philippines—so even though his focus was on the European Theatre of Operations, he always appreciated the global nature of the conflict. But those, in some sense, are just the proximate causes of Ike as liberator. At the core were the moral sense and values instilled in him as a child by his parents.

Ike was raised to treat people with kindness and grace, to view and treat the janitor with the same respect as a prime minister, for example.

JL: He believed in fairness and, thanks to his education at West Point, saw honor in treating others as he would want to be treated. What the Axis powers did by launching the war, and their conduct in waging it, violated all these beliefs. I don’t think it out of bounds to say that Ike saw the war in heroic terms, even if he also understood that war brought death and destruction, which also weighed on him a great deal. The sacrifice though was worth it to stop the evil that had been unleashed upon the world.

ED: Describe Eisenhower’s reactions to what he witnessed while touring the Ohrdruf concentration camp.

JL: Incomprehensible disgust is the quick answer. Prior to his visit, he viewed the war in sports terms, of “us versus them,” and of course “good versus evil.” But he had no idea just how bad the Nazis were.

Ike knew that the Germans had a labor camp system that utilized prisoners before he saw Ohrdruf, but I don’t think he had any idea what that meant in Nazi terms. Ike and nearly everyone who saw the camps, spoke in terms of the survivors being “living skeletons,” of the smell that emanated from the camps, and of course of the emaciated bodies of the dead, mass graves, and ashes of cremated remains.

Encountering the camp system stripped away any illusion Ike might have had that the Germans were an honorable opponent. They were a force of evil that had to be stopped. The visit to Ohrdruf also spurred something else in Ike, a desire to make sure, in his words, that he would “get this.” When aides tried to get him to leave, he insisted on staying longer, on visiting building after building, of talking to prisoners, trying to understand what he was seeing and what had happened there. And that visit, which lasted a few hours, not only brought about moral clarity but also spurred him to action. Ike ordered the camp (and the scores of others his forces were already encountering) documented and requested that the United States and British governments send official delegations, including politicians, newspaper editors, and others—including his men—to visit the camps.

There would be no way for people to dismiss what he saw as “propaganda” – this was why the war was worth fighting. But it wasn’t just Allies Ike wanted to see the camps, he also made sure that German civilians also viewed the camps and saw what had been done in their name. Such barbarous acts could never be forgotten or allowed to happen again.

ED: What role did Eisenhower play in “denazifying” Germany?

JL: Prior to the spring of 1945, I don’t think Eisenhower had thought that much about denazification. His job was, first and foremost, to defeat the Nazis. He was aware of some of the discussion, most notably the Morgenthau Plan, about what a postwar Germany might look like, but largely felt that such grand planning was above his pay grade. That being said, just as would be the case with the displaced persons liberated from the camps as the Allies pushed into Germany, the military was in the best position to administer to an occupied Germany. The U.S. had spent some time pondering previous occupation duties, including the short-lived occupation in Germany following the First World War. But such planning was academic, and Ike already knew that plans drawn up behind the lines tended to require changes once they were implemented in the real world.

Eisenhower transitioned almost immediately from his role as Supreme Allied Commander to military governor of the U.S. zone of occupation. And for the next six months of 1945, he took what Washington, and his own men gave him, and turned policy into reality.

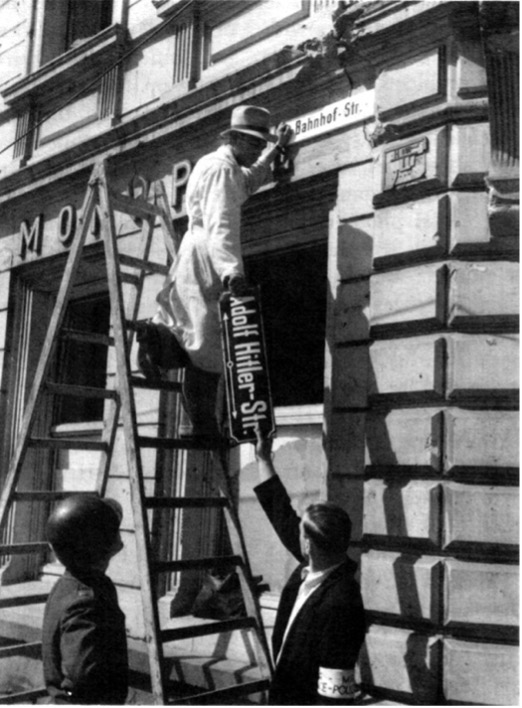

At the center was denazification. That meant renaming German streets, taking down Nazi monuments (or things that might become memorials)—often with dynamite. It meant determining who was a real Nazi (as opposed to, maybe, just a member of the party). It meant removing Nazis from positions of influence, incarcerating, trying, and convicting those deemed to be war criminals. And it meant rebuilding the country, from its educational institutions, its political structures, and its physical infrastructure. Ike was responsible for all this—and more, including feeding and caring for millions of displaced persons and preparing everyone for the coming winter.

ED: How would you describe Eisenhower’s leadership style, and did he apply that style differently to times of war and times of peace?

JL: Eisenhower’s leadership style, especially once he was in the White House, is often referred to as the “hidden hand.” That is, he worked behind the scenes after having assembled a team, which resulted in achievements that often seemed effortless. What was often missed is how much work goes into making sure things seem routine. Indeed, there is a tendency to take such leadership for granted.

His style grew out of his own experience as a staff officer in the Army—where he worked with an amazing cohort of officers over the course of his rise to Supreme Allied Commander, each of which taught him different things in terms of what to do or what not to do. It is hardly surprising, looking back, that Ike brought the staff system with him to the White House. Eisenhower was the first president to have a chief of staff (Sherman Adams), who helped coordinate the flow of information from the expansive executive branch within the administration.

This new arrangement jived with the already existent cabinet system. While everyone had their own specific roles, people were expected to share ideas freely, given (largely) free rein to get their jobs done, and were tasked with working together towards larger goals. The system is highly effective, especially when the person at the head sets the overall goals, boundaries, and parameters.

And few who worked with him, either in war or peace, ultimately doubted that anyone but Ike was firmly in control.

ED: Your final chapter, “Never Again,” focuses mainly on Eisenhower’s postwar career. To what extent do you view him as a Cincinnatus-type figure?

JL: Cincinnatus is usually linked to Washington, and for good reason. But there is something to the applying the story to Ike as well. From the time he left Kansas for West Point, Ike was in the military—truly a public servant. Even his presidency of Columbia University after World War II was marked not so much by his entry into private life, but by continually being called back to serve.

His decision to seek the Republican nomination in 1952 was based on his conviction that the alternatives were not up to the job of leading the nation in the Cold War. He knew he could lead and believed he had to.

It was not until he left the White House that he was able to retire, literally, to a farm. The home in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania was the first home he had ever owned. However, like Washington, Ike in retirement remained engaged.

Part of that was his own personality and perception of duty, part of it was because those seeking the White House after him, Republican and Democrat alike, understood that few Americans were as respected nationally nor knew what it took to lead—whether on the battlefield or in the Oval Office—the way Ike did.

ED: What has your research taught you about America’s founding principles and history?

JL: That the founding principles are central to the American experiment. One of my undergraduate professors, the late Bernard Sheehan, said something in class once about the Constitution being America’s body—it is how we function; but that the Declaration of Independence is our soul—it is what we aspire to be.

The principles enshrined in those documents—and the history surrounding them—are what we fight over. But when it comes to Eisenhower’s story, they are also what we fight for.

JL: They are what differentiate us (especially in our own view) from other nations—friends and foes alike. They are the things that make the American way of life possible. These are the things Ike swore to protect and defend, as both an officer and as president. In short, they matter.

ED: What’s one thing you wish that every student knew about American history?

JL: Oh, there are many things!

When it comes to Eisenhower, that he saw America as a moral force for good in the world. That our ideals matter and though we may not always live up to them, that doesn’t lessen the importance or centrality of those aspirational ideals. They can make the world, nation, and individual better even when we fall short of them. Believing this does not preclude a “warts and all” telling of American history, nor is it a hagiographic version of American exceptionalism. Rather it is an understanding that history is made by real people, who made real decisions, which had real consequences.

It is a humbling thing to know one’s history, and to walk in another’s shoes—especially when they are the rather large shoes of someone like Eisenhower.

ED: Thank you for your insights and time!

Elliott Drago serves as the JMC’s Resident Historian and Editorial Manager. He is a historian of American history and the author of Street Diplomacy: The Politics of Slavery and Freedom in Philadelphia, 1820-1850 (Johns-Hopkins University Press, 2022).