An interview with Professor John Ragosta

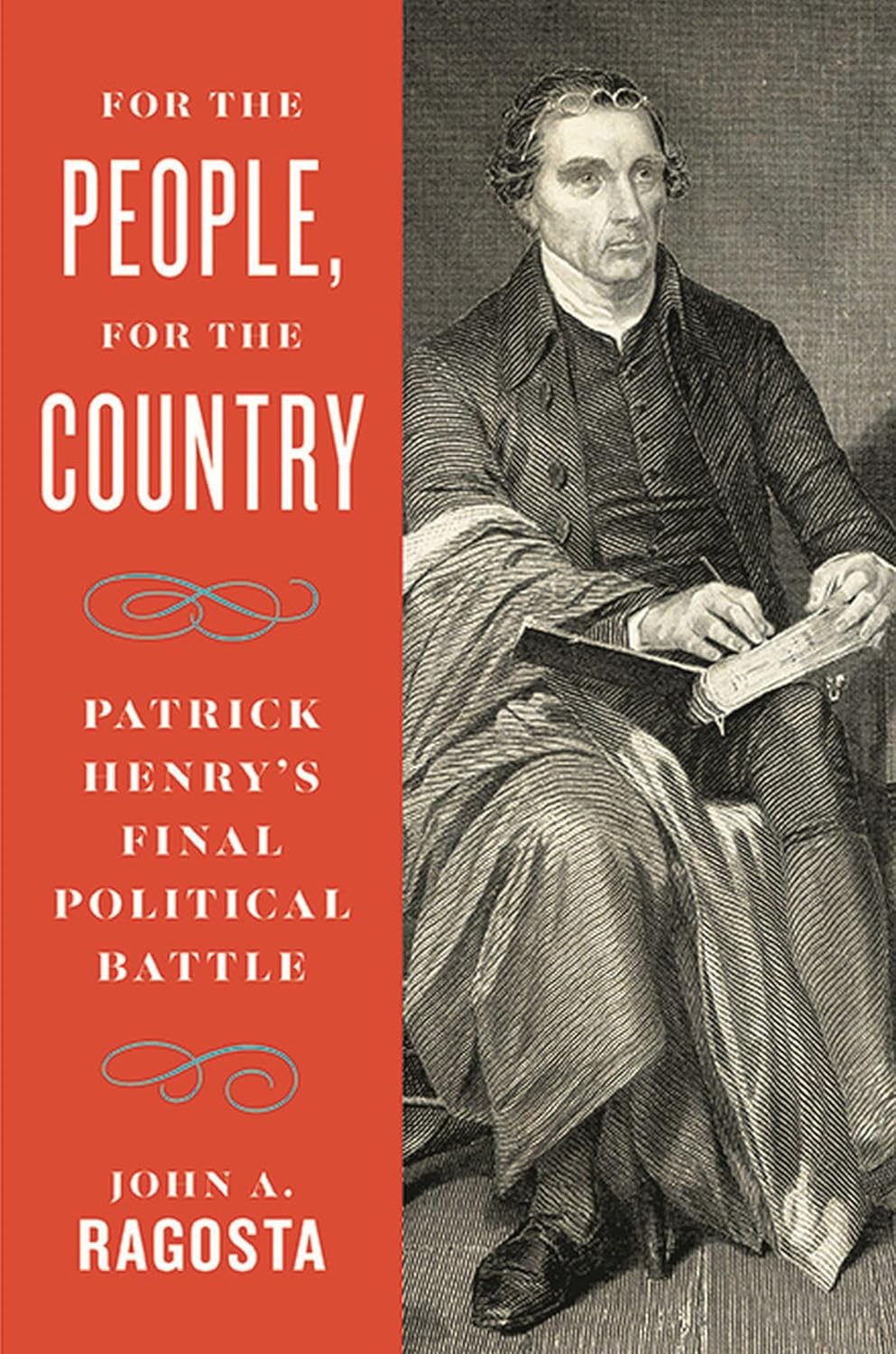

JMC Resident Historian Elliott Drago sat down with JMC Faculty Partner John A. Ragosta to discuss his most recent book, For the People, For the Country: Patrick Henry’s Final Political Battle. Dr. Ragosta is a historian at the Robert H. Smith International Center for Jefferson Studies at Monticello and a fellow at Virginia Humanities.

For the people

ED: Thank you for taking the time to sit for this interview. Before we start discussing Patrick Henry, recently the Department of Education reported that only 13% of eighth grade students scored proficient in history. What would you say are the biggest consequences of that number?

JR: This is a very important question, and what the Jack Miller Center is doing to bring attention to it is very timely and important. I was doing a tour at Monticello with school children the other day, and I said, you know, Jefferson believes education is critical because you either educate the masses and the masses will therefore control the aristocracy, or the aristocracy will control the people.

Jefferson said that the taxes that will be paid to educate the people are not “the thousandth part of what will be paid to kings, priests and nobles” – the aristocracy – “who will rise among us if we leave the people in ignorance.” His idea was that people must understand their own history and government or the government will control us.

History education really is fundamental. I tend to be a hopeless optimist, but if we are going to succeed as a nation we really need to do something about civics.

ED: How did you get into studying Henry, and what sort of questions interest you when you research and write on him?

JR: I sometimes come to things serendipitously, which I think a lot of historians do – but they just don’t admit it. I was reading a letter doing other research, and I came across a letter from January 1799. George Washington was writing to Patrick Henry saying that the nation is in a crisis, and you (Henry) need to come out of retirement to save the country; we’re on the verge of dissolution, the union is falling apart, and there may be a civil war. I thought, well, that’s fascinating; what’s that all about?

They were complaining about Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, the Virginia and Kentucky resolutions, hyper partisanship, and radical states’ rights. Here’s this battle with Patrick Henry and George Washington on one side, and Thomas Jefferson and James Madison on the other. So that launched me into studying Henry. I was fascinated because if you ask people about Patrick Henry, almost everybody’s heard of Henry. But if you ask them, what did Patrick Henry do, they might remember seven words: “give me liberty or give me death.” Yet that ignores what Patrick Henry was really trying to talk about, which was we need to govern ourselves and that we have to have the right to govern ourselves – which was why Washington wrote to him in 1799 to help save the nation. His understanding of governance in a democracy is really what interested me.

Historical quirks

ED: What were some of the personality quirks that make Patrick Henry, Patrick Henry?

JR: I think we need to start with the gift of gab, because even Jefferson, who hates Henry, says, you know, he’s the greatest orator of all time and that he seems to me “to speak as Homer wrote.” That’s high praise from Jefferson.

According to contemporaries, Henry was quite successful in criminal trials because he would talk to the jury and get in their heads. Henry enjoyed telling jokes in court, and would get the jury laughing – and then he’d have them crying.

He has this real ability to understand where people are coming from on a deep level, which I think he developed from working in a store and speaking with the common man.

ED: Tell us a little more about Henry’s views on local control.

JR: Henry’s very well read. He’s reading Enlightenment philosophy and adopts Montesquieu’s view that the people have to govern themselves – but it has to be local so, in effect, you must know the people you’re governing.

For example, when the Constitution was adopted, one of Henry’s objections was that the electoral districts were too big. You know, today, we would think it’s almost comical; it’s like 30,000 or more people per elected representative. Henry says that in the Virginia legislature small electoral districts are essential. In a small district, any landowner or business owner is going to know a local legislature and likely personally know someone who sits in the General Assembly. Now you may not be best friends, but you’re going to know who they are, where they live, and how they make a living. Henry says that’s local governance, which is a very Montesquieu-esque idea.

It was the same problem before the Revolution: In the British empire you have the Parliament 3000 miles away, and none of those people were paying taxes here nor understood the problems in Virginia. That was anathema to him. He said, that doesn’t work. His objection to the Constitution is very similar, i.e., that you’re going to have people sitting in Philadelphia or New York, who don’t know Virginia, controlling Virginia.

ED: Let’s return to Henry’s relationship with Jefferson. What were the sources of Jefferson’s animosity towards Henry?

JR: Henry is a little older than Jefferson, who’s a little older than Madison. Henry is in the legislature first, as I said, and he’s sort of the progressive. He’s the young buck of his age when he gives that speech against the Stamp Act in 1765. Thomas Jefferson, who is a law student at that time, talks about going to the Virginia House of Burgesses and listening to Patrick Henry. When Jefferson was elected to the House of Burgesses a few years later, they all understand that Henry is the leader of this new young revolutionary group of political leaders.

But Henry and Jefferson have a bitter falling out in 1781, when the British invade Virginia and drive the Virginia Legislature out of Richmond – including then-governor Thomas Jefferson. The legislature relocates to Charlottesville, and the Redcoats drive them out again. Jefferson’s term had technically expired, and he writes the head of the legislature. He says, look, I know I’m eligible for a third one year term, but don’t elect me because the Redcoats are running rampant. Jefferson says that Virginia needs a military governor, so don’t elect me.

Virginia does elect a governor with military experience, Thomas Nelson, and he leads the Virginia militia at Yorktown. Nelson leads on the battlefield while Jefferson leaves when the legislature is chased out. Jefferson does not go with the government to Stanton; he goes with his family to Lynchburg, and it appears that he has abandoned the state.

As a result, the legislature launches an investigation of Jefferson, basically accusing him of incompetence, cowardice, and dishonor. It’s not clear who’s responsible for that investigation, though Jefferson blames Henry. Jefferson writes to James Monroe a few years later, saying that this “wound on my spirit […] will only be cured by the all-healing grave.” Now historians, by the way, disagree on whether Henry was really behind this investigation. I think he probably was behind it, but it’s not clear from the record. But it doesn’t matter: Jefferson thought Henry was responsible and never forgave him.

ED: So how does your new book fit into the historiography on Henry?

JR: The climax of the book is what we’ve been talking about — Henry coming out of retirement to defend the Constitution that he had opposed because the people voted for it. The title is For the People, For the Country: Patrick Henry’s Final Political Battle. That’s who Henry was fighting for, the people and for the country.

I think my book is going to change our view a little bit. Many historians argue that this state’s rights idea was percolating after the ratification of the Constitution until it exploded in the Civil War. What I think I show is, no, a controlling states’ rights died with the Constitution.

Henry and the antifederalists were saying that we need stronger states’ rights, but once they lost, nobody kept calling the Constitution a compact of independent sovereign states. Nobody is talking about nullification, and nobody is saying the states can interfere with federal laws until the Alien and Sedition Acts of 1798 when Jefferson, in desperation, writes the Kentucky Resolutions.

I argue that Jefferson really resurrects the idea of a compact of independent states. That’s what Henry wanted, but Henry would be the first to say, “I lost.”

JR: The second thing that the book changes is how we understand Jefferson and Madison considering the Kentucky and Virginia Resolutions. The conventional wisdom is a seamless transition between those resolutions and Jefferson’s election to the presidency in 1800. That’s completely wrong. The resolutions were hyper partisan states’ rights documents which argued that states can interfere with the federal government. That’s 1798.

Jefferson’s party, the Democratic Republicans, are shellacked in the 1799 congressional elections; they lose badly in the south because it sounds like they’re talking about secession. My view is that Jefferson and Madison realized that they went too far in their partisanship during the late 1790s. In fact, they pull back, with Madison writing Jefferson within 10 days of the Virginia Resolutions being adopted, saying that maybe we went too far. Quite unusual for politicians to admit that maybe they went too far! Yet they do what we want politicians to do: they realized that they’ve gone too far.

So in 1798, they were focusing on the Alien and Sedition Acts as a violation of states’ rights, and everybody was saying you’re going to destroy the union. By the time the 1800 election, they’re focusing on the freedom of the press. And that’s a winning argument.

Jefferson has been accused of hypocrisy in his presidency for over 200 years, because he won’t do as president the things he was talking about in the 1790s, including his radical states’ rights views as well as limiting the federal government and executive. I don’t think it’s hypocrisy, I think that he and Madison very intentionally realize that no, we have a country to run, and the country is valuable. They seem to have also realized that such partisanship almost destroyed the country in the 1790s.

And so if you read Jefferson’s first inaugural address in that light, “we are all Republicans, we are all Federalists,” it’s a much more honest, deeper, and significant statement of Jefferson, which is so critically important today: what unites us is more important than what divides us. We are one nation. We can’t let the nation dissolve because of our political battles.

ED: What can Henry teach Americans living today about our nation’s founding principles and history?

JR: I think it’s what I was referring to earlier that when I do tours for children. It seems to me if I’m trying to explain democracy to a child, there’s two critical elements.

We all know that the majority rules, but the second piece can be contentious: a democracy means that you may lose. And when you lose, you must live with what the opposition does.

JR: Now, if you go to the ballot box you can try to win the next election – but you must accept what your fellow citizens and neighbors have decided. It’s very easy to forget that democracy means that you may lose because none of us like losing – Americans don’t like to lose. However, in an election there’s always going to be a lot of losers; that’s the way the system works. If the losers forget that their job as American citizens is to live under the government that they did not vote for, the country won’t work.

I mean, what Henry says is if we can’t live within the constitution that we adopted — again, he opposed the Constitution, but WE adopted it — if you can’t live within that Constitution, there will be monarchy. He said that’s the only choice. If we can’t live within the Constitution that is our Constitution, it’s a monarchy. I think that Henry teaches us the critical lesson of what do you do when you lose.

ED: Thank you! We look forward to learning more about Patrick Henry!

Elliott Drago serves as the JMC’s Resident Historian and Editorial Manager. He is a historian of American history and the author of Street Diplomacy: The Politics of Slavery and Freedom in Philadelphia, 1820-1850 (Johns-Hopkins University Press, 2022).