Hitting the road with history

JMC’s Elliott Drago spotlights the sights and sounds of Gettysburg in honor of the 160th anniversary of the battle

These dead shall not have died in vain

Gettysburg, 1863 – 2023

This July marks the 160th anniversary of the Battle of Gettysburg. Over the course of three days in 1863, more than 160,000 Union and Confederate soldiers fought in the bloodiest single battle in the Civil War. Confederate General Robert E. Lee’s bold quest to take the war north into Pennsylvania ultimately proved futile, forcing Lee to march his beleaguered and bloodied army back south. Lee’s defeat at Gettysburg represented a pivotal turning point in the Civil War, as it proved that Lee could lose a battle and dashed the Confederacy’s hopes to invade the North and force a negotiated peace.

The photo essay below commemorates this historic battle and anniversary. While it may not be possible to see all these sites in one day, we encourage all Americans to visit Gettysburg to see where so many paid the ultimate price for defending our nation’s founding principles.

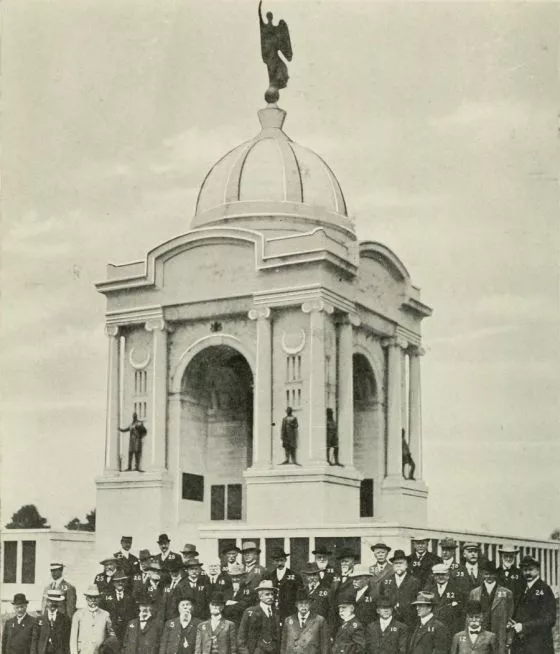

Pennsylvania State Memorial Monument

We begin our tour at the Pennsylvania State Memorial Monument. Dedicated in 1910, the memorial stands majestically along Cemetery Ridge, the primary defensive position of the Union Army during the battle. It remains the largest monument on the Gettysburg battlefield. Over 34,000 Pennsylvanians saw action at Gettysburg, with some 1,100 dying in battle. Their names are emblazoned on bronze tablets on the monument’s base and interior. Pennsylvania Governor Andrew Curtin and President Abraham Lincoln’s statues flank the west entrance, while General George C. Meade (the Union commander at the battle) and Pennsylvania’s own General John F. Reynolds command the north entrance. The 7,500-pound Winged Victory statue, forged from melted down Civil War cannons, stands triumphantly atop the dome.

Gettysburg Visitor Center and Cyclorama

We continue our tour at the Gettysburg National Military Park Museum and Visitor Center. There you can take in the breathtaking and massive cyclorama, a panoramic painting depicting Pickett’s charge, the final Confederate assault on Union positions on July 3rd, 1863.

Originally displayed in 1884, the cyclorama is 50-feet tall and over a football field in length, and captures the arguably most climactic moment of the three-day battle.

Viewed from one perspective we see cavalry gallantly charging over farmland; from another we see wounded men limping away from the fight; yet another perspective draws our attention to Confederate General George E. Pickett’s men making their infamous failed uphill charge to dislodge the Union’s defensive position on Cemetery Ridge. The cyclorama invites visitors into the heat of battle, with the sounds of warfare – bullets whizzing, cannons thundering, and rifles cracking.

Gettysburg Civil War Reenactment

A trip to Gettysburg wouldn’t be worth a piece of hardtack if it didn’t include an authentic reenactment. Although Civil War reenactors gather at Gettysburg at various times throughout the year, June and July gatherings remain the most popular. From June 30th through July 1st, the Gettysburg Battlefield Preservation Association hosts a reenactment of the battle on Historic Daniel Lady Farm, a site used as a field hospital by Confederate forces during the battle.

More than simply soldiers marching and firing their rifles, these reenactments also feature cavalry, artillery, and sharpshooter demonstrations, as well as living history exhibits depicting everyday life, circa 1863.

Old timey baseball

Speaking of everyday life, most people forget that Civil War soldiers spent most of their military careers in camp. Besides drilling, soldiers taught each other a variety of games, including baseball. To modern eyes, 1860s baseball gameplay might look strange or even primitive, but the sport was key in bringing together men from different regions of the country. The game’s special place in building camaraderie and boosting morale is on full display July 15th and 16th, when Gettysburg hosts “the greatest gathering of 19th century baseball clubs.” The levity of the game, the sportsmanship of the players, and the roar of the crowd provide a bit of gaiety for fans seeking respite from the sobering realities of the battlefield. So in the spirit of the 1860s version of the game, bring your wool uniforms, leave your gloves at home, and play ball!

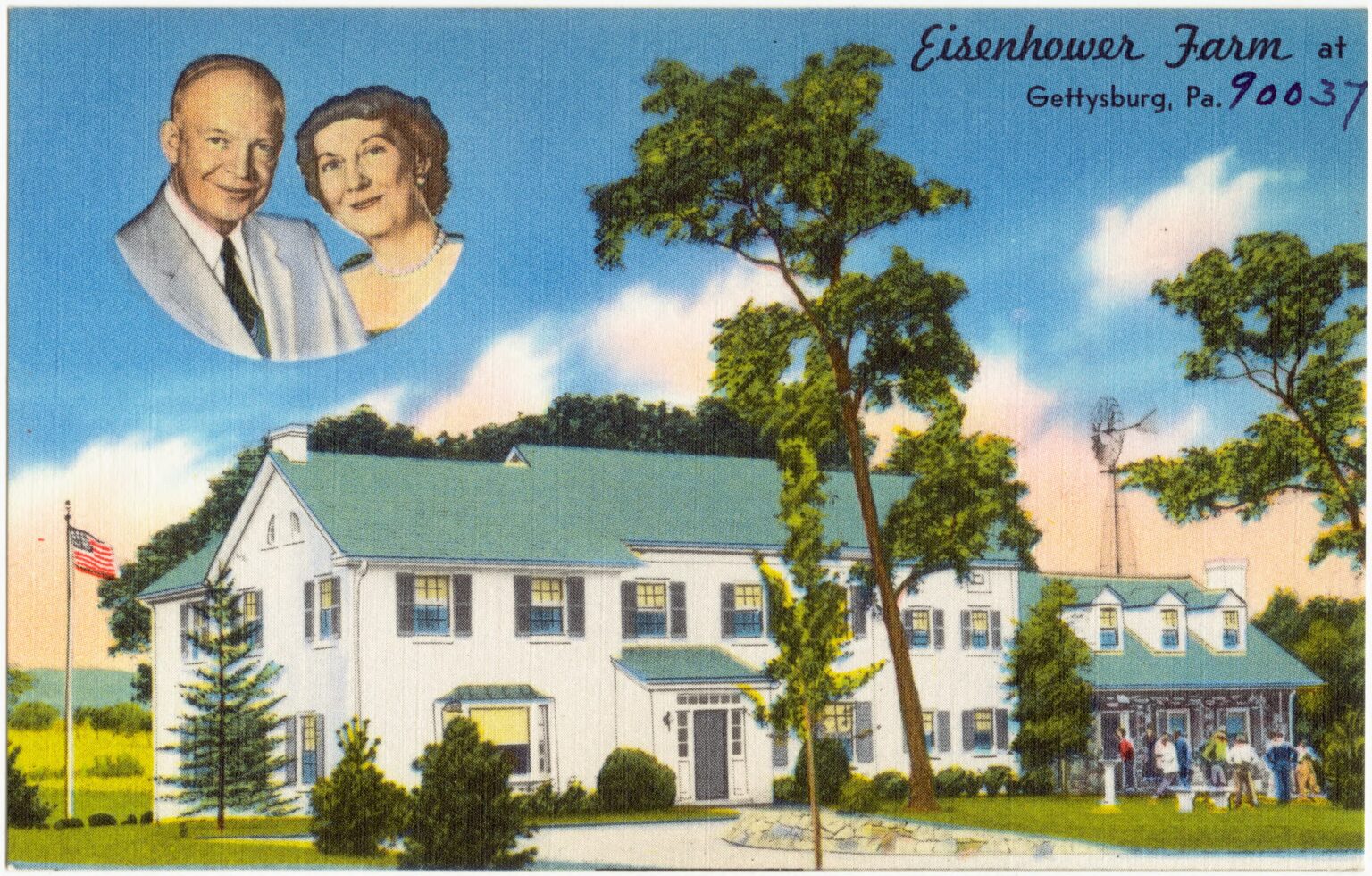

Eisenhower National Historic Site

Oftentimes visitors to Gettysburg will notice that Civil War reenactors aren’t the only soldiers marching about the town. Every summer, at least one company of World War II reenactors arrives in Gettysburg. But why? Simple: Dwight D. Eisenhower’s farm and weekend retreat is adjacent to the battlefield. There the former Supreme Commander and President hosted world leaders in the thick of the Cold War, including Winston Churchill, Jawaharlal Nehru, and Nikita Khrushchev. Believe it or not, Eisenhower even gave battlefield tours for a few lucky guests! While not specifically related to the 1863 battle, visitors can learn more about the man who oversaw the defeat of Nazi Germany and became one of the nation’s finest and most beloved Presidents.

The Shriver House and Museum

The next two sites are the Shriver House and the Jennie Wade House. Every room in the Shriver House is “frozen” in time: here we see the civilian side of the Civil War. The Shriver family planned on opening a saloon in Gettysburg before the war came. This plan was interrupted when George Shriver enlisted in the Union Army, leaving his wife Hettie to manage household affairs and take care of their young daughters. When soldiers arrived in Gettysburg in 1863, Hettie and her daughters left for the countryside for safety. Little did they realize that their house, situated between Little and Big Round Tops, would be directly exposed to the gunfire and carnage of the battle. At one point, Confederate sharpshooters commandeered the Shriver’s attic, where they themselves would suffer fatal gunshots. The Shriver House reminds visitors of the sacrifices made by ordinary people, and like many historic homes, helps us imagine what everyday life was like in the 1860s.

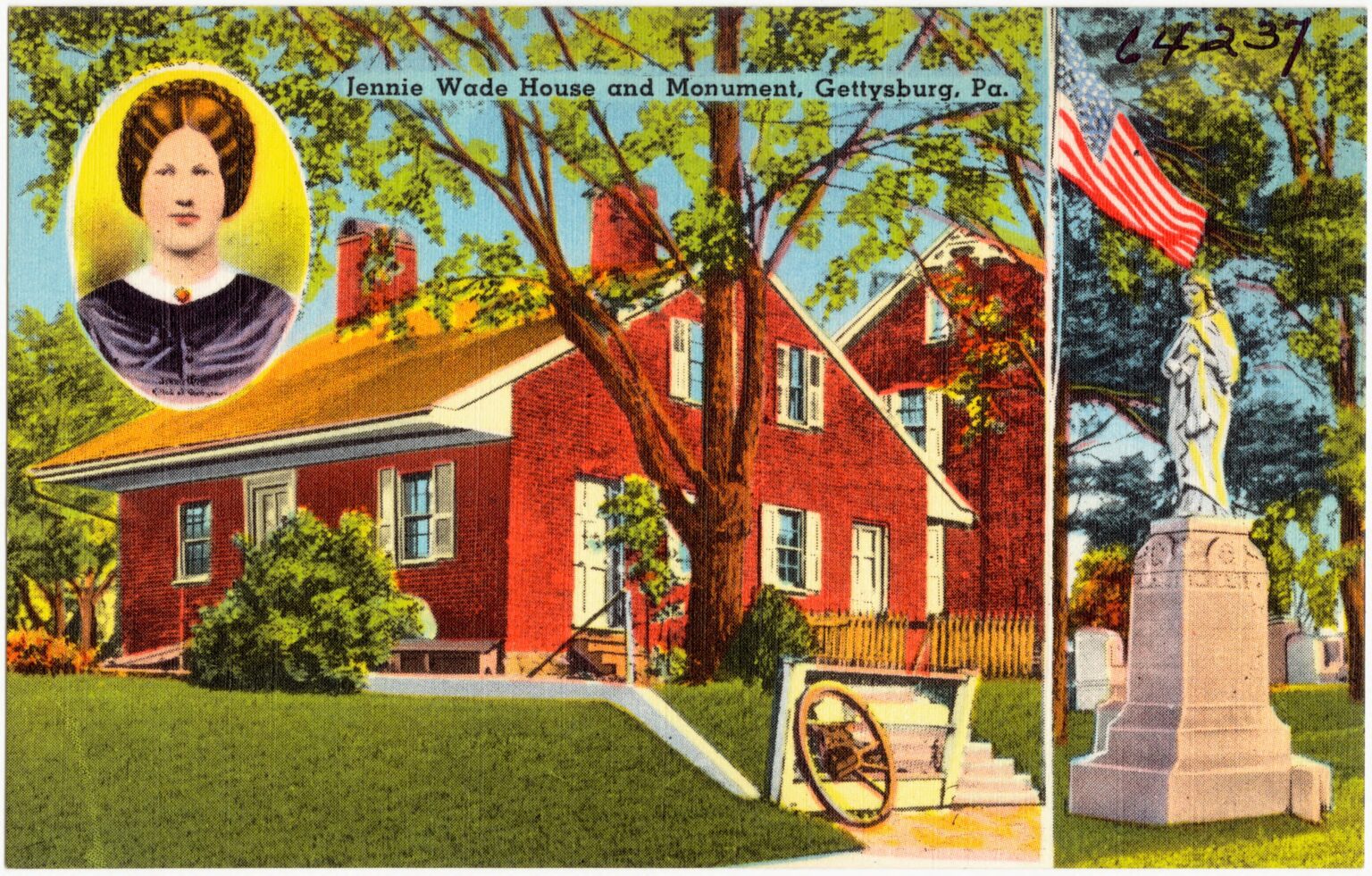

Jennie Wade House and Museum

The Jennie Wade House also captures the domestic life of the Civil War era, though with an additional layer of tragedy. While kneading bread in her kitchen, 20-year-old Jennie Wade was mortally wounded by a stray bullet, becoming the only civilian to die during the battle. Wade’s house looks very much like how she left it, replete with authentic furnishings and artifacts from that fateful day. Guides in period attire lead visitors around the house, telling the story of Wade’s life and the larger consequences of living as a civilian in a warzone. In short, the story of Jennie Wade and the history contained within her house urge visitors to consider the sacrifices that happened on and off the battlefield.

Coster Avenue Mural

Truly off-the-beaten-path, the Coster Avenue Mural depicts the clash between Colonel Charles Coster’s Union forces and the Confederate forces led by General Harry Hays. Taking position in a brickyard, Coster’s men played an important role on the first day of battle by providing a “rearguard” action to cover the retreat of the Union Eleventh Corps. Outnumbered three to one, their desperate struggle resulted in the deaths of over 500 Union soldiers and the taking of the brickyard by the Confederates. This brief, yet vital and heroic action of Coster and his men is immortalized on the mural, which is tucked away in a quiet residential neighborhood in Gettysburg…our lack of a picture means that you have go visit and see for yourself!

Culp’s Hill

Located on the southeast outskirts of Gettysburg, Culp’s Hill saw action all three days of the battle despite being “the least visited and under interpreted major part of the battlefield.” Union forces needed Culp’s Hill to protect their supply lines and more importantly, to block a Confederate invasion of Baltimore and Washington, D.C. Consequently, the Confederates did everything they could to take the hill, using overwhelming force with each charge and even attacking at night. Fortunately, the hill stayed in Union hands. Visitors to Culp’s Hill will note dozens of monuments in the area, and perhaps stop to remember how the Union’s defense of this unremarkable hill helped protect the nation’s capital and pave the way for victory.

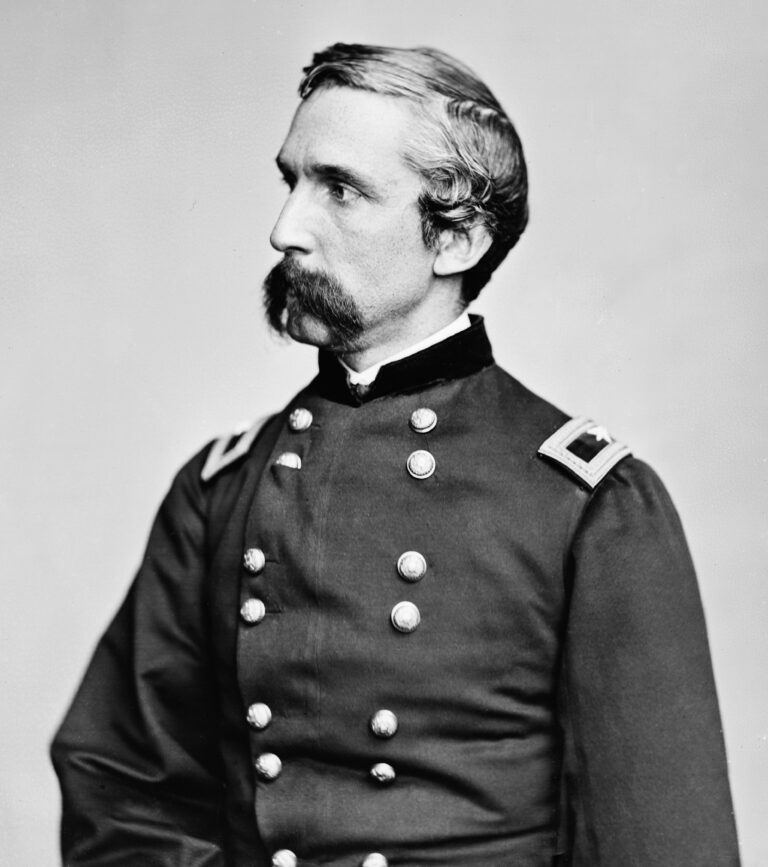

JMC’s Laura Graham contributes her favorite must-see Gettysburg site! Read her account of Joshua L. Chamberlain’s heroic efforts to push Confederate forces down Little Round Top on the second day of the battle, effectively blunting their advance and shifting the tide of the battle in the Union’s favor.

Little Round Top

Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain caught my imagination as a child and never let go.

From his unlikely origins described in Ken Burns’ immortal documentary: “The quiet college professor from Maine, who, on the hilltops of Pennsylvania, would execute an obscure textbook maneuver that would save the Union Army, and, perhaps, the Union itself.”

To his rallying cry on Little Round Top: “AFFIX BAYONETS!”

I would later write my college history thesis on his role in the Surrender at Appomattox but today we will focus on Gettysburg.

Colonel Chamberlain of the 20th Maine was only 35 years old when he commanded his men at Gettysburg. Fending off Confederate charges from the peak of Little Round Top, his heart must have been pounding as the ammunition ran out and the Confederate charges continued again and again up the hill.

Perhaps any teachers reading this would say that his classroom management experience kicked in, along with his natural leadership skills as he remained collected enough to think of, and then rally his exhausted men into, that “obscure textbook maneuver” (technically called a right wheel forward). Chamberlain’s gambit worked: he drove the Confederates from the hill and by doing so, entered into the pantheon of American heroes.

What happened to Chamberlain after the war? Happily, he would continue to flex his leadership skills, going on to become president of Bowdoin College and Governor of Maine.

Maine may seem a long way from “the hilltops of Pennsylvania” but, having visited both, I can attest that they share a not-dissimilar natural beauty.

If you have never visited Little Round Top, go. If you have visited, go again. There is nothing quite like walking through those forested hills where so many gave the Last Full Measure of Devotion for our Sacred Union.

Devil’s Den

The enormous boulders of Devil’s Den witnessed some of the bloodiest fighting of the Civil War. On July 2nd, Confederate sharpshooters used the boulders as a deadly vantage point, picking off Union soldiers and officers to seize Union cannons and disrupt the Union lines. The aftermath of battle revealed the accuracy of Union cannons – scores of Confederate sharpshooters lay strewn across Devil’s Den.

In fact, one of the most iconic – if staged, as was common among Civil War photographers desiring morbid and evocative pictures – photos from the Civil War was snapped at Devil’s Den. At some point in the fighting, a young Confederate sharpshooter was killed near the Devil’s Den “barricade” (a haphazard wall of boulders). Contemporaries theorized that the concussion of a cannonball and not the shrapnel itself killed the man. Standing in the exact same spot where this soldier was killed 160 years ago is a surreal and unforgettable experience.

Gettysburg Museum of History

Billed as “a museum like no other,” the Gettysburg Museum of History is a treasure in the heart of Gettysburg. Admission is free, and the private collections contain not only Civil War relics, but also artifacts from other American wars. The exhibits are simple yet effective in bringing visitors closer to the material realities of the war. For example, one exhibit features two bullets, one Union and one Confederate, that collided with each other midair during the battle – in other words, so much lead was fired that individual bullets could (and did) smash into each other. Another exhibit showcases letters written by Jennie Wade; another contains a Confederate schoolbook with “story problems about killing Yankees.” The bugles, rifles, uniforms, belt buckles, and bullets presented by the museum captivate as much as teach.

The David Wills House

David Wills was a skilled lawyer and respected member of the community when the war came to Gettysburg. As litters bearing wounded and dying men streamed into town during and after the battle, Wills opened his house to these men in their time of need. Later, the leaders of Gettysburg would gather at Wills’ house to formulate a plan to handle the staggering amount of bodies, both human and horse, that laid unburied in the pastures and forests surrounding the town. In November 1863, President Abraham Lincoln arrived in Gettysburg to dedicate the Soldiers’ National Cemetery. Wills arranged for the President to lodge with him. One of the upstairs bedrooms would become the site where Lincoln finished a “few appropriate remarks” for the dedication of the cemetery – today known as the Gettysburg Address.

Soldiers’ National Cemetery

Four months after the battle, Lincoln delivered his Gettysburg Address at the dedication of the Soldiers’ National Cemetery. His remarks crystallized the nation’s aims to define itself by the precepts of the Declaration of Independence, namely, that our nation is “dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.” The town of Gettysburg had barely recovered from the fighting of that summer. Lincoln and the crowd of attendees were greeted by the realities of war: half-buried bodies, creaking wagons piled high with the dead, and inescapable fetid odors. Residents of Gettysburg understood the toll of war and the carnage moved Lincoln as he spoke. His words were more than an honor to the dead: his words called on the nation to realize the entire essence of the American project. Could Americans handle the pangs of a “new birth of freedom”? Could Americans preserve a “government of the people, by the people, for the people?” In short, Lincoln asked Americans to realize their tremendous responsibilities – the “great task before us” – to those who died fighting and consecrated the ground of Gettysburg.

Gettysburg reunion site

The final stop on this curated tour of Gettysburg is the famous reunion site, located right on the battlefield itself. The two most memorable veteran reunions occurred in 1913 and 1938. In 1913, the town hosted the largest-ever Civil War veteran reunion, with over 53,000 veterans attending, representing 46 out of 48 states. The festivities included speeches, individual unit reunions, and the dedication of the Pennsylvania State Memorial. The 1938 reunion featured a crowd over of 200,000 people, including almost 2,000 veterans (average age 94), out of the 8,000 Civil War veterans still alive at the time. At both reunions, the survivors shook hands across the rock wall known as “the Angle.” Located atop Cemetery Ridge, the Angle – or “Bloody Angle” – was where Union soldiers fended off Pickett’s disastrous charge on July 3rd, 1863. The area around the Angle includes the “Copse of Trees” Pickett’s men used as a landmark as they charged up the hill. Historians later christened the Angle and Copse as the “high-water mark of the Confederacy,” that is, the point reached by Confederate forces in their desperate bid to take Cemetery Ridge from the Union.

The highlight of the 1938 meeting came with President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s dedication of the Eternal Peace Light Memorial. “Immortal deeds and immortal words,” Roosevelt began, “have created here a shrine of American patriotism.” Alluding to the Gettysburg Address, Roosevelt reminded the crowd of the ongoing challenge of maintaining a popular government under one flag. With war brewing in Europe, Roosevelt transformed this challenge into the responsibility of every American to “save for our common country opportunity, and security for citizens in a free society.” The memorial consists of a Maine granite base and an Alabama limestone shaft, capped with a bronze urn that houses the eternal flame. Inscribed on the monument are the words, “Peace Eternal in a Nation United,” a powerful message for any generation of Americans, but perhaps especially, this generation.

We hope you enjoyed our curated tour of Gettysburg. 160 years after the battle, Americans have made significant progress in the pursuit of achieving our founding ideals – but the task before us remains incomplete. By visiting such historical sites as the Gettysburg Battlefield, we can better appreciate the sacrifices made to preserve our political traditions and history. In closing, we hope that this tour inspires you to emulate our predecessors and do the necessary work to ensure that “the last, best hope” of the United States of America “shall not perish from the earth.”

Elliott Drago serves as the JMC’s Resident Historian and Editorial Manager. He is a historian of American history and the author of Street Diplomacy: The Politics of Slavery and Freedom in Philadelphia, 1820-1850 (Johns-Hopkins University Press, 2022).