An interview with Dr. Jane Calvert

JMC Resident Historian Elliott Drago sat down with JMC Miller Fellow Jane Calvert. Dr. Calvert is the Founding Director and Chief Editor of the John Dickinson Writings Project.

America’s first celebrity

ED: What inspired you to become an American historian?

JC: America’s dysfunctional political culture inspired me to become an historian. I wanted understand why Americans of different political persuasions relate to each other as they do, how they understand the role of government in our lives, and what, if anything, could be done to lessen the partisanship that divides us. When considering graduate school, I initially thought I might study philosophy, literature, or political science, as my father had. But he suggested intellectual history—the history of ideas. It made sense to me to study how early Americans saw themselves and their government(s) and what our founding principles were. I would focus on the colonial era.

But any change must be done peacefully without destruction of people, property, or the unity of the polity. So they invented two things: First, the theory and practice of civil disobedience—that is, the public, nonviolent breaking of unjust laws with the intent to raise public awareness about the injustice and obtain repeal of those laws—and, second, the amendable written constitution. These two modes of reform have contributed to our constitution’s surviving for over 230 years.

ED: What do you consider an underrated moment in the American founding?

JC: To my mind, the most underrated moment of the Founding era was in 1765, when John Dickinson published an untitled broadside addressed simply to “Friends and Countrymen.” It appeared in November, shortly after he returned from the Stamp Act Congress in New York, where he had taken the lead on writing the two documents that were sent to England objecting to the new taxation. Until this point, although there had been many writings against the Stamp Act and in favor of American rights, they were all theoretical treatises by elite men aimed at other elite men.

The voice of reason

Americans in general knew why they should resist the Stamp Act, but they didn’t know how they should do it. As a result, they flailed between two extremes—engaging in violent riots and destruction of property on the one hand, and evading the act on the other. “Friends and Countrymen,” short and clear, was directed to ordinary Americans. It explained in simple terms why the Stamp Act was dangerous—that it served as a precedent that would allow future taxation—and, for the first time, it provided practical instructions for how Americans should resist it.

Rejecting both violence and passivity, Dickinson advised a middle way, the civil disobedience that Quakers had used for 100 years to resist unconstitutional laws. He explained that Americans should simply “proceed in all Business as usual, without taking the least Notice of the Stamp Act.” The people would thus repeal the law virtually and thereby compel Parliament to repeal it actually. Americans responded enthusiastically to the broadside, and Dickinson continued to advocate this method for the next ten years.

ED: Why should Americans pay more attention to John Dickinson?

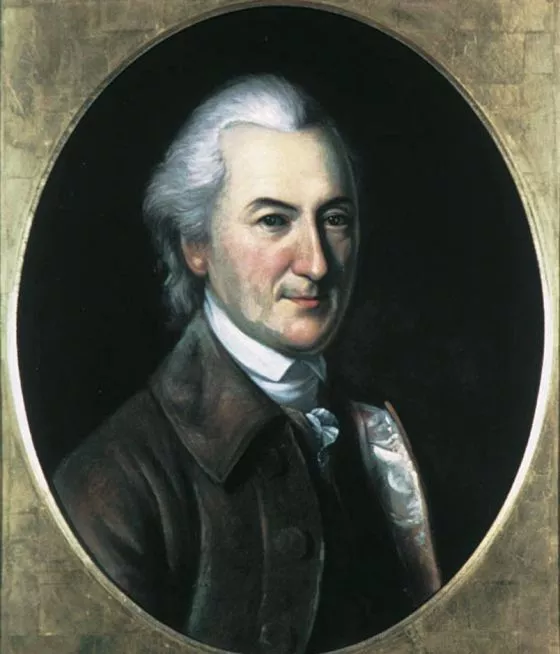

JC: John Dickinson was America’s first celebrity, the leader of the resistance to Britain in the decade before independence, and a seminal figure in the Founding era. A highly trained lawyer with expertise in constitutional law, he was the only major figure who was in America for the entire Founding era, 1763 to 1789. In addition to writing more for the American cause and holding more public offices than any other figure, he also had more military experience than most.

The Founding cannot be understood without his writings and actions. Americans at the time believed that he was responsible for leading them to declare independence. But independence was not his aim; securing American liberties was. This, he believed was most likely under the British constitution. Thus, although he did not vote on or sign the Declaration of Independence, he did more than any figure to ensure that the Revolution would succeed, including delaying separation; working to prepare the country through uniting the people, drafting the nation’s first constitution, shoring up the military, and planning foreign diplomacy; and taking up arms.

Dickinson’s centrality to the narrative is only part of his importance. Of the leading Founders, he also was the only major figure who attempted to actualize the central idea of the Declaration of Independence as we understand it today—that all people (not only white, propertied, Protestant men) are created equal and have rights worthy of protection. He freed those he enslaved during his lifetime and advocated the rights of women, Blacks, Indians, laboring people, and prisoners.

ED: You founded the John Dickinson Writings Project (JDP) in 2010. Tell us about how this project originated.

JC: At one of my first professional conferences—maybe even the very first—after I gave my paper on Dickinson, the director of the Scholarly Editions Program at the National Endowment of the Humanities approached me and asked if I would collect and publish Dickinson’s papers. I said I wasn’t interested; I was an historian, not an editor. But he then sent me a link to the application for funding, which, when I saw how complicated it was, only confirmed that I didn’t want to take on this project.

But as I finished my first book on Dickinson, I was astounded by how much he had written. It was clear that someone should publish his papers, and I was the only one to do it.

JC: As I began work over the next years, I learned that there had been several partial and failed attempts to do this project over the last 200 years. Dickinson himself collected fourteen documents in a two-volume set in 1801. Paul L. Ford published 21 documents in one volume in 1895, but he was murdered before he could produce the second volume. Other projects ended or never launched because of professional squabbles, the sheer size of the project, which is massive, and lack of institutional support. I have provided a detailed history of the JDP in Volume One of The Complete Writings and Selected Correspondence of John Dickinson.

ED: What would you say has been the most successful aspect of the JDP?

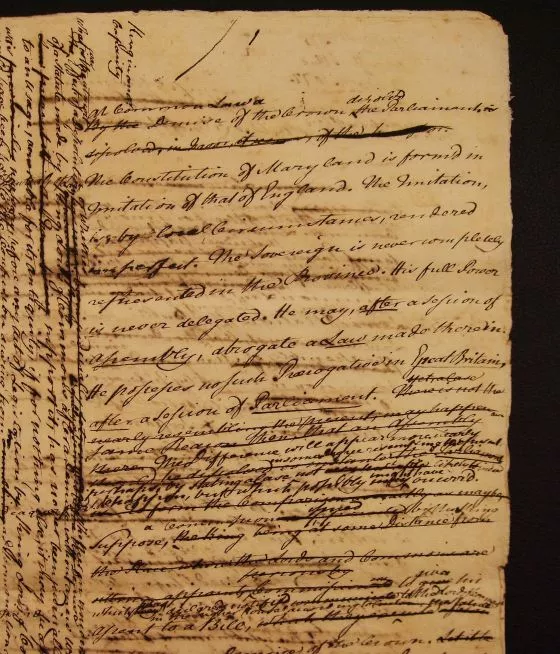

JC: The fact that we have published anything means that the JDP is successful. But we have now produced three volumes, two of which won an award for “Best Historical Materials” from the American Library Association. More specifically, I would say that our transcriptions of Dickinson’s manuscripts mark our success. To render his otherwise inscrutable documents legible is a remarkable feat. In the early stage of this project, I honestly didn’t think it was possible.

ED: Have you encountered any difficulties with collecting Dickinson’s writings?

JC: The entire JDP is difficult. We struggle mostly with funding and staffing, and the actual work is exceedingly challenging. Projects of this size such as the Papers of Benjamin Franklin, John Adams, George Washington, or any of the other major Founders, were established in the mid-20th century when support was plentiful. They have had staffs of five to ten full-time, highly skilled professional documentary editors working for decades with powerful host institutions behind them.

For the first decade of the JDP, it was all me, with no training, with only one or two part-time, contractual workers, and virtually no institutional support.

Only recently have I secured enough funding to hire two full-time people in addition to the two contractual editors. I don’t pay myself. We now have institutional partners, although still no financial support.

Putting the pieces together

JC: Dickinson’s papers are also more difficult to work with than most other Founders’ papers. In addition to his drafts being extraordinarily messy, he frequently used Latin, legal terminology, now-obscure literary references, and idiosyncratic abbreviations. So his work is illegible until it has been deciphered and transcribed by a trained paleographer. And, because his manuscripts are frequently untitled, undated, have unnumbered and unordered pages, they haven’t been organized in the archives. This means we really have no idea what we are looking at until an item has been transcribed, the text has been ordered, and research has been done to determine what or who he is writing about and when.

Frequently it is lawsuits between obscure individuals, which could contain gems of insight into his life and jurisprudence; but sometimes it is a hugely important document, such as a draft of the 1776 Plan of Treaties. Heretofore attributed solely to John Adams, this document was the basis for American foreign policy up to World War II. Now we know there was another probably earlier draft by Dickinson.

ED: Given your expertise on Dickinson, has the JDP uncovered any writings by Dickinson that surprised you?

JC: The JDP is the main reason I have expertise on Dickinson. Before I founded it and began work, I only thought I knew about him. That said, there were two documents that came as a great surprise.

The first was the scrap of a draft provision in the Articles of Confederation that used gender-inclusive language to protect the rights of women to freedom of religion and freedom of public speech. I believe this was the most revolutionary moment of the Revolution. Unfortunately, Dickinson’s colleagues weren’t having it. They excised the entire religious liberty clause from the final version of the Articles of Confederation. But after finding that draft, I began seeing how Dickinson promoted women’s rights and welfare in many other ways. I never imagined I would be comfortable calling him a feminist, but now I am.

The second surprising discovery was a single page with notes on both sides for something Dickinson titled “Indian Letters.”

It seems to have been a rough sketch of an essay or essays he wanted to write that would have fit into the category of literature called “Indian romance.”

It was to be a fictional story about a young man who was raised by Indians. He didn’t know how to read and write until they took a British man hostage, who taught him and opened up his world. He then went to a city (presumably Philadelphia), where he observed Anglo-American culture. He was appalled by what he found—superficiality, materialism, overly complicated laws, people fighting about religion. He found Indian culture much superior. Then he met a Quaker woman, who taught him about Quakerism, which he found to be closest to the truth. He couldn’t help falling in love with her. It seems clear that his story has some biographical elements.

It was remarkable to get a sense of Dickinson’s views on Indians, among other things. I don’t think anything ever came of these notes, but this document makes me wonder about what else Dickinson might have published that we haven’t found or may never find.

ED: What is next in Dickinson scholarship?

JC: There are at least two big things coming: The first is my new book, Penman of the Founding: A Biography of John Dickinson (Oxford University Press), available on July 1, 2024. Written for a general audience, this will be only the fourth biography of Dickinson and the first that covers his entire life and does so accurately.

The second thing is a book of scholarly essays on Dickinson presented by various scholars at the John Dickinson Symposium in October 2022. Covering topics including Indian relations, criminal jurisprudence, taxation, the military, and aging, the essays present fascinating findings on Dickinson based on research in the materials collected by the John Dickinson Writings Project.

ED: What has your research taught you about America’s founding principles and history?

JC: My research has taught me, first, that realizing America’s founding principles is probably impossible, and, second, that we shouldn’t stop trying to do so.

The Founders recognized that the principles they valued and sought to implement in the new nation were, at best, ideals that were imperfectly realized in their own time.

For example, the most important principle was virtue, by which they meant disinterested (i.e., selfless) behavior by citizens. But because all around them they saw the opposite—men seeking to enrich themselves at the expense of others—they attempted to construct a system of government that would account for Americans’ shortcomings. Yet they also knew that their design could only do so much, and if we didn’t at least try to put the common good over individual gain, the republican experiment would fail.

In this way, we are continually trying to form “a more perfect union.”

ED: What’s one thing you wish that every student knew about American history?

JC: Americans should know that nothing in our history has ever been inevitable or unanimous. This fact is especially true with defining moments, such as declaring independence or ratifying the Constitution. Major events such as these have occurred through non-linear processes and were hotly contested by people at the time. To comprehend these moments, it is vital to understand the historical context at the time and the different perspectives of the historical actors involved—those who were in favor, those opposed, and those somewhere in the middle. Americans should listen to the dissenting voices both in their collective past and the present and expect the unexpected.

ED: Thank you for your insights! Let’s all spread the word about John Dickinson!

Elliott Drago serves as the JMC’s Resident Historian and Editorial Manager. He is a historian of American history and the author of Street Diplomacy: The Politics of Slavery and Freedom in Philadelphia, 1820-1850 (Johns-Hopkins University Press, 2022).