An interview with Susan Brynne Long

JMC Resident Historian Elliott Drago sat down with JMC Scholar Susan Brynne Long to discuss her work on early American military history and captive management during the War for American Independence. Ms. Long is a Ph.D. student at the University of Delaware.

Getting their feet wet in local government

ED: Why did you become an American historian?

BL: As an undergraduate, I fell in love with Lin Manuel Miranda’s musical Hamilton. I like to joke that I’ll be the first person to get their PhD because of the show. My obsession led me to declare an American Studies major, which allowed me to take more early American history courses that counted towards the completion of my degree than a History major would have.

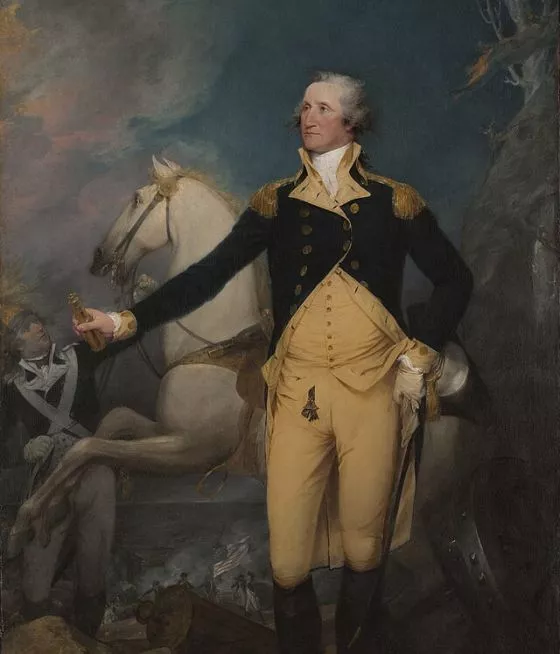

During my sophomore year, our cohort visited George Washington’s Mount Vernon. I can pinpoint the exact moment that I knew I would dedicate my life to the study of early America: when I was walking up the main staircase of the home, our guide informed us that the railing I was holding was original. I was immediately addicted to the high that I felt when it dawned on me that I was touching the same surface that Washington touched. I returned to Mount Vernon as an intern that summer, and during my free time, visited the archives at the Fred W. Smith Library on the estate. It was during those visits that I began developing the project that turned into my senior thesis and has since evolved into my dissertation.

ED: What made you decide to study prisoners of war during the American Revolution?

BL: In the Fred W. Smith Library archives at Mount Vernon, I found a transcription of a diary written by John Blatchford, an American prisoner of war during the Revolutionary War. I later discovered that the diary was widely published during Blatchford’s lifetime. It is truly a terrific account, in every sense of the word. Among other exploits, Blatchford claimed that after being taken prisoner, he escaped from a British ship on which he was working as a deckhand, beat up a sentry, and eventually ended up performing forced labor on a British East India Company spice plantation, from which he escaped by fighting off a tiger.

My fascination with his account led me to discover the vast amount of secondary literature about American prisoners in British captivity. I wanted to do something different, so I decided to flip the switch to look at British prisoners in American captivity, a topic that had received comparatively little scholarly attention. In the past decade, it has received more, and my work has been a part of that shift.

Did you know?

ED: How did the issue of prisoners of war represent a struggle between local and national authority?

BL: Prisoners of war were a problem that no one wanted at the start of the conflict, and everyone wanted by its end. Congress did not have the time, energy, or resources to dedicate to prisoners captured by the Patriot forces during the early years of the war, and so foisted them onto the states. The great financial burden posed by prisoners on host communities led state and local authorities to begin allowing prisoners to find employment among inhabitants in and around detention centers. Americans became accustomed to this additional labor source, as well as to their ability to influence prisoner allowances via their local committees of safety.

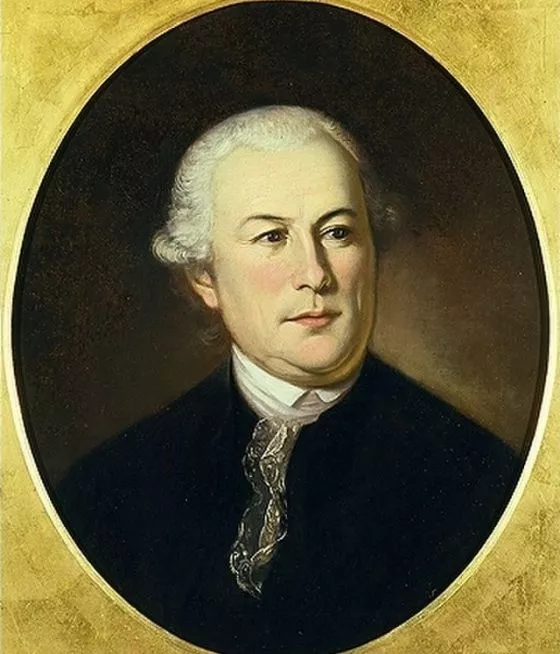

In 1777, following the Battles of Trenton and Princeton and the sudden influx in the prisoner population in the American interior, Congress took a renewed interest in prisoners. George Washington appointed Elias Boudinot to become the nation’s first Commissary General of Prisoners. Boudinot had the unenviable task of consolidating responsibility for prisoners from among the many state and local authorities to which they had been scattered by the start of his administration. In the process, Americans lost influence in the prisoner management system, as well as, in many cases, prisoner labor. This arrogation of power led to tensions between Americans on the local level and the Continental Army, which represented the emerging national authority of the Continental Congress.

ED: You write a lot on John Gooch. Who was he, and what makes his life so fascinating?

BL: John Gooch was a Captain in the Continental Army and the quartermaster of the barracks in Rutland, Massachusetts, one of many prisoner detention centers used by Americans during the war. He is important to my research insofar as he represents an important moment during the war wherein the Continental Army increased its role in prisoner administration. Before and after Boudinot took power from state and local authorities and established it anew in the Department of Prisoners, the militia guarded prisoners in detention centers and during transportations.

In the fall of 1777, the Battles of Saratoga changed that. British General John Burgoyne’s defeat resulted in the capture of nearly 7,000 prisoners of war.

BL: The militia, the ranks of which were infamously porous and undependable, was insufficient to guard a prisoner group of this size.

To supplement the number of guards, the Continental Army oversaw the housing and provisioning of the prisoners, who came to be collectively known as the “Convention Army,” named for the surrender terms signed by Burgoyne and American authorities at Saratoga. Gooch was among the cadre of soldiers assigned to the care of the Convention troops, a capacity in which he encountered first-hand the aforementioned tensions that emerged after the establishment of the Department of Prisoners.

ED: How did soldiers spend their time while imprisoned?

BL: How soldiers spent their time often depended on their rank. Officers could expect to be welcomed among the upper-class members of their host communities.

In Reading, Pennsylvania, a major detention center, one British officer was a frequent attendee of dancing parties hosted by locals. Officers were able to do such things because they often had parole, or a written allowance to roam freely within a pre-set area in their host town.

Not every officer used their allowances wisely. Reports of British officers becoming drunk and rowdy at taverns and other public places exist for most known detention centers. Particularly during the early years of the war, such behavior often resulted in restrictions and imprisonments for captives, enforced by committees of safety. Outside of these instances, a captive British or German officer might spend his day socializing, attending church, or visiting with fellow officers and local upper-class Americans. Enlisted men did not have as many freedoms as officers, but still enjoyed some mobility while in captivity. Hundreds if not thousands of prisoners, mostly German, found employment in the American interior during their captivity. If not hired out, enlisted men and officers might have enjoyed the company of their wives and children, who sometimes accompanied their husbands and fathers into captivity.

ED: What were some of the differences between how the Americans and the British handled prisoners of war?

BL: In all conflicts, how the belligerents characterize the conflict has a direct bearing on the treatment of enemy prisoners. In the case of the American Revolution, the British understood the American actions as those of rebellious colonists engaging in a revolt against the empire. The Americans saw the conflict as a war between two sovereignties: the United States and the British Empire.

For Americans in British captivity, the gap between these two bookends meant generalized neglect by their captors. For British prisoners, the pursuit by Congress and its army of recognition by European countries of American sovereignty spelled, in general, better treatment. This was because Americans sought to demonstrate their compliance with European standards of warfare, which included protections for military prisoners.

BL: British and German prisoners of war still suffered in captivity in various instances, but on the whole, they fared better in American captivity than did Americans in the hands of the British. Some similarities between the ways in which prisoners were treated include officer paroles and the ability to receive money and supplies from one’s own side while in captivity.

ED: What did the postwar world look like to former prisoners of war?

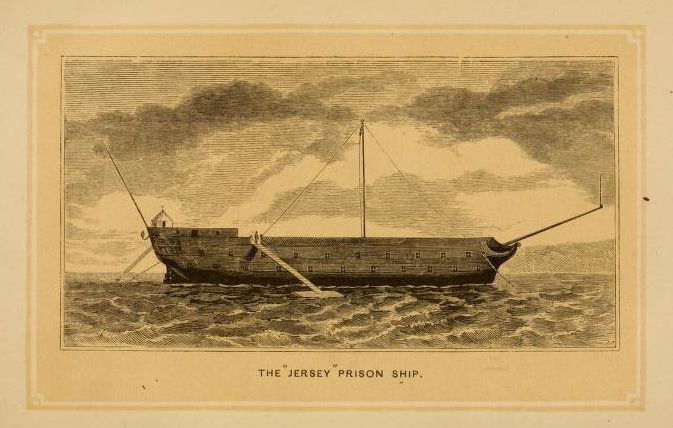

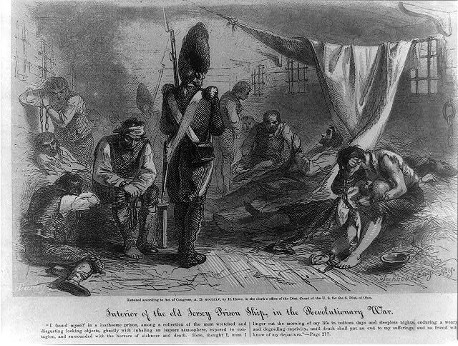

BL: American prisoners of war returning home from captivity had a celebrity status, if they chose to acknowledge and indulge it. As John Blatchford’s narrative indicates, there was money in sensationalism in the post-war period, particularly if you had experienced captivity among the British. Reports of Americans suffering in the hulls of British prison ships began circulating as early as 1777 during the war, and had incensed the American reading public.

At the end of the conflict, there was a good deal of interest in hearing the stories of former prisoners, and some opted to publish their captivity narratives. For British and German prisoners, life after captivity could mean a return to army life or a brand new start. Some German prisoners opted to stay in the United States after the war, having found work or marriage during their captivity. After the war, these men lived mostly in areas of high concentrations of German-American settlers, including Lancaster, Pennsylvania.

ED: You mention that at times, some Americans viewed the Continental Army as an occupying force. Why was that the case?

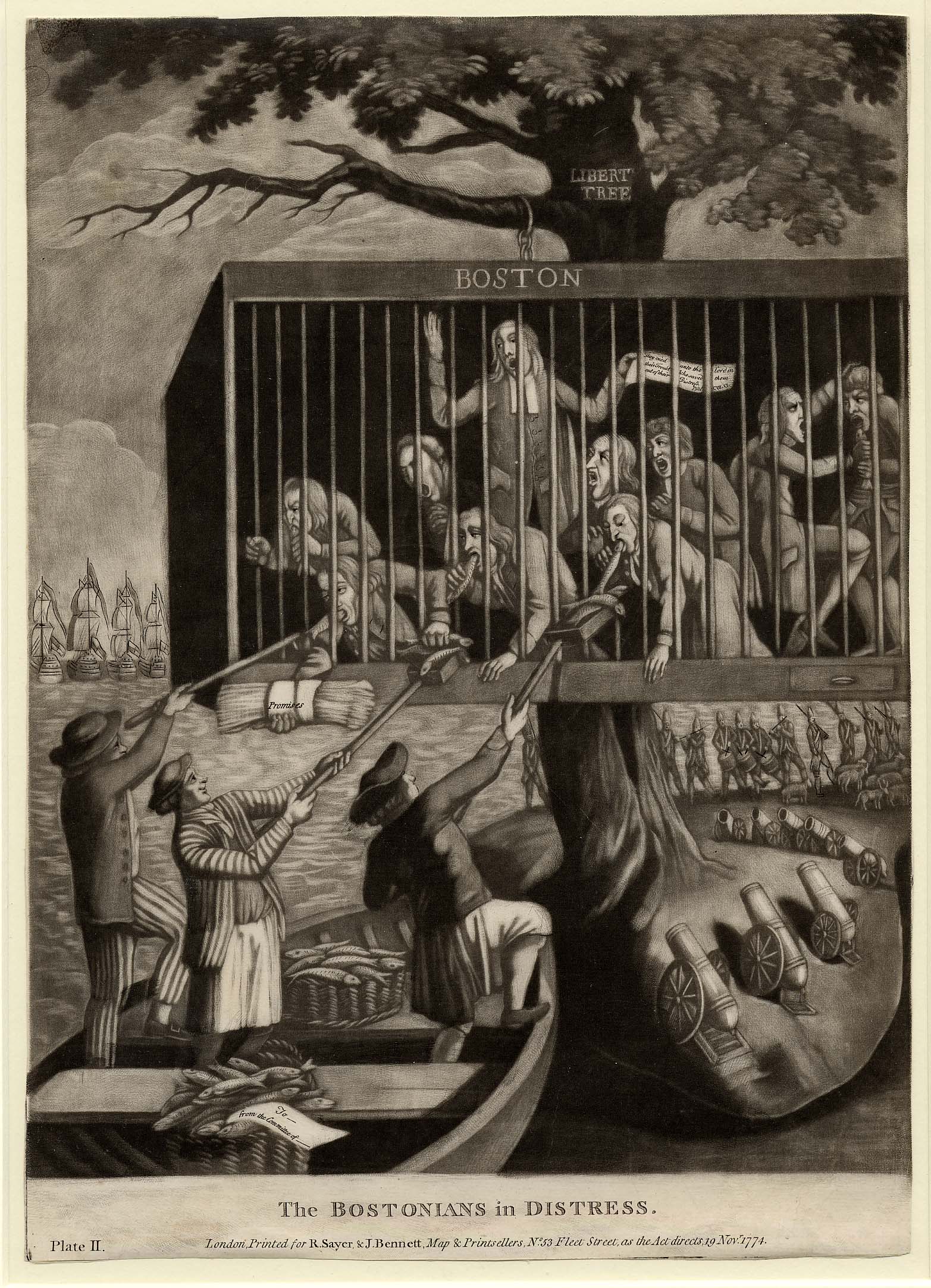

BL: This isn’t a particularly new argument, though it is as applied to prisoner administration. Particularly after the rage militare of the early war years wore off, Americans became less patriotic and more protective of their goods and money, both of which ran scarce very quickly after the start of hostilities. During the blockade of Massachusetts in 1774, Americans had eagerly sent money and supplies to their suffering brothers in Boston.

Americans in 1777 and beyond often hid their food and goods from American requisitioning parties in order to sell it for specie (hard money) to the British Army. When the Continental Army requisitioned goods, it felt a little different to an enemy invading force for Americans suffering to make ends meet in a wartime economy. In terms of prisoner administration, Americans became accustomed to relying on the labor of prisoners during the early years of the war. And even if they didn’t employ prisoners, captive populations were subject to the authority of inhabitants in and around detention centers.

Provisional wartime authorities, most notably committees of safety, relied on public support for their legitimacy. In this way, they readily obliged inhabitants to enforce harsh restrictions on prisoner populations, particularly officers. When the Continental Army and the Department of Prisoners assumed responsibility for prisoner populations, Americans lost the authority that they had wielded during the early years of the war. So, the Continental Army was an occupying force in that it usurped power from the existing authorities, namely, the people.

Inspirational spotlight

My project draws attention to a moment in American history wherein an alternative military future for the nation existed. This military future involved Americans exercising influence in the conduct of common defense via their local governing institutions.

Based on colonial precedent, the possibility of this approach being instituted on a continental scale in the new nation was foreclosed upon with the establishment of the Department of Prisoners.

When Elias Boudinot began arrogating power from local and state governments as their interests, in turn, became increasingly provincial, Americans lost influence in the production of continental defense. This is an important insight, as it highlights the fact that the American Revolution took, as well as gave, authorities to early Americans.

ED: What is your next project?

BL: My next project follows military commanders from the Revolutionary War into political leadership during the early republic, investigating how and why the militia retired as a social institution in the northern states while it endured in the South.

ED: What’s one thing you wish everyone knew about the American political tradition?

BL: I think Americans owe a bit more attention to state and local governments when thinking about the American founding. While the delegates to the Continental Congress achieved great compromises that constructed a continental political system, virtually all of them got their feet wet in local and state governance. Moreover, many of them occupied multiple worlds, the local, the state, and the national, simultaneously, and remained in many ways representatives of their states and localities even as they served as national delegates.

ED: Fascinating topic, we look forward to reading more of your work! Thank you!

Elliott Drago serves as the JMC’s Resident Historian and Editorial Manager. He is a historian of American history and the author of Street Diplomacy: The Politics of Slavery and Freedom in Philadelphia, 1820-1850 (Johns-Hopkins University Press, 2022).