An interview with Professor Fred Beuttler

JMC Resident Historian Elliott Drago sat down with JMC Faculty Partner Fred Beuttler to discuss his research, archival advice, and former role as the Deputy Historian of the United States House of Representatives. Dr. Beuttler is a Liberal Arts Instructor in the Graham School of Continuing Liberal and Professional Studies at the University of Chicago.

Always find the person with the key

ED: Thank you for taking the time to interview with us! What inspired you to become a historian?

FB: I have known since I was eight that I was called to be a historian. Maybe it was from a love of reading and reading history. Maybe also from a trip to Gettysburg that we made when I was younger. I was encouraged in this by my parents, especially with books about the American Civil War.

Freshman year in high school I was taught by a dynamic teacher, who made Western Civilization come alive. He taught freshman year, and then AP European history senior year, and when I finished freshman year, I couldn’t wait until I became a senior. That senior year was an amazing class. I studied with one of my best friends for the AP exam, and we both got “fives”, the highest grade, giving us 8 semester hours of college credit.

In college, I decided to major in political science, thinking it more “relevant” than history, but I knew I had to get my Ph.D., so figured I could return to history then. I started grad school at Northwestern and soon realized my undergraduate history preparation was inadequate when my advisor told me I should just go to law school. I dropped out, then began a rigorous master’s program, where I really learned how to become a historian from a marvelous teacher and mentor. From there I went to the University of Chicago, where I finally finished my doctorate.

The inspiration was a series of charismatic teachers that modeled being a historian for me.

ED: What is your area of specialty, and what sparked your interest in that topic?

FB: I first started graduate school with an interest in colonial America. I had a great teacher who really opened up the subject, and so I wrote my 200+ page master’s thesis, using primary sources. When I applied for my PhD program, I did it in colonial America, but between application and admissions, I changed my mind to twentieth-century America, because I thought that would increase my job prospects. I took a lot of courses, more than I needed, in several departments, looking for something I wanted to write about.

Then one day, I was browsing the stacks in the library, and came across eighteen volumes from the Conference on Science, Philosophy, and Religion, which was subtitled, “and their relation to the Democratic Way of Life,” all between the years 1940 and 1968, and I thought, “Hey, I’m interested in all of those topics!” And that became my dissertation topic, called “Organizing an American Conscience: The Conference on Science, Philosophy, and Religion” (CSPR for short).

ED: Describe your favorite research “rabbit hole,” and the results of that quest.

FB: CSPR was sponsored by the Jewish Theological Seminary, on Manhattan’s Upper West Side, so I contacted them. That started the processing of the CSPR archives. I combined some oral history of a few of the secretaries and editors, with time in the archives. The problem I faced was that the Seminary’s special collections were designed for medieval manuscripts and rare books, so it was only opened four hours a day, and the staff was used to giving out only a couple of files.

As a poor graduate student with two little kids at home, I could only go out to NYC two weeks or so at a time, so how was I to get through boxes and boxes of academic paper, including over 10,000 pages of verbatim transcripts? There were no smartphones in those days, nor could I xerox, so I was forced to take notes. How to work through all that material?

Then I found the woman with the key.

She had been the administrator for CSPR, and she had the key to the Seminary’s attic, where the filing cabinets were stored. My initial request started the processing of the archives, but they had only done a couple of years’ worth, with the rest just stored upstairs. She was the administrator, so she gave me access. So I would spend mornings in the attic, and then afternoons in special collections, and then back to the attic.

And that’s how I was able to finish research. My lesson – always find the person with the key.

ED: How did you become the Deputy Historian of the U.S. House of Representatives, and what did your position entail?

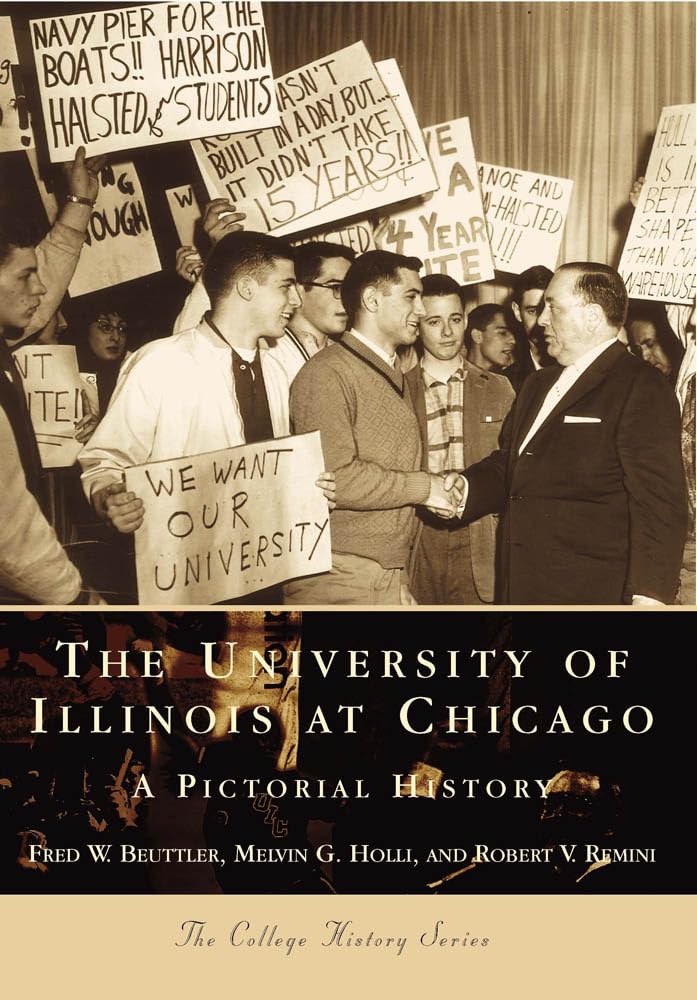

FB: I was the Associate University Historian at the University of Illinois at Chicago, working with the University Historian, Robert Remini, on a university history project. Remini had been commissioned to write a history of the House of Representatives, after he had finished his biographies of Henry Clay and Daniel Webster. I took care of the university history project, while he was writing the history of the House.

When the Speaker of the House wanted to reestablish the Office of the Historian, I applied for it, but after meeting with Speaker Hastert, he offered the position to Remini, with me as “Deputy Historian.” I asked about the title, rather than “Associate,” but his staff said, “In Washington, each department has only one deputy.” So I moved to DC and set up the Office, running it day by day. The resolution that created the Office had as its mandate “to promote and preserve the history of the House.” The Senate had a historian, who had been there for thirty years at that point, and there was already a small historical office under the House Clerk, which put together the biographical directory of Congress, as well as a small website, so we did not need to duplicate that.

We reestablished the Office of the Historian as a non-partisan office under the Speaker, with an emphasis on four things: developing an oral history project of current and former members; press relations for attribution, on any question that came up on House history; presentations on House history to various internal and external organizations, such as state bar associations and civic ed organizations; and finally, the House Fellows Program, which was an intensive week-long seminar on the history and practice of the House, for high school history and government teachers. When I left the Office after five and a half years in 2020, the Office was moved under the Clerk, and the House Fellows Program ended.

ED: What can the “Great Books” teach us about America’s founding principles and history?

FB: As one from the University of Chicago’s Graham School, I prefer to use the term “The Great Conversation,” which is within the “great books,” but goes beyond them.

The Great Conversation is a dialogue over the last 2500 years on the great ideas by great thinkers of the past, it focuses on the liberal arts, that is, the art of being free.

FB: The American founders were deeply immersed in this history, as they investigated republican and democratic principles, about how states were organized, how power was exercised, and how societies collapsed.

They learned ideals of republican virtue, but also how to build a constitutional system that was aware of a fallen human nature, where ambition could be checked by ambition, enabling the people to hold their officials accountable and where centralized power is kept within limits.

Reading Thucydides, they saw the dangers of faction and civil war; reading the Pentateuch and John Locke they understood that humans were created equal and endowed with inalienable rights. Reading Adam Smith, they saw how individual opportunity created the real wealth of nations. And reading Livy, Machiavelli, and Montesquieu, they learned how to separate powers and build a stable constitutional republic. As the “Great Conversation” continues into the future, many of these founding principles — of equal human dignity, individual opportunity, and ordered liberty — have shaped and will continue to shape our history.

ED: What’s one thing you wish that every student knew about American history?

FB: There are several related things, that “all men are created equal and endowed with certain unalienable rights,” and that it was

The genius of the Founders to develop a system of constitutional government that allows the growth and self-government of the people through a combination of liberty and law.

FB: And that it was the vision of Abraham Lincoln to see that the purpose of the Constitution was to fulfill and realize that proposition, that the Constitutional framework was to implement the Declaration’s aspirational claim.

ED: Thank you for your inspiring answers! We look forward to hearing more about your work!

Elliott Drago serves as the JMC’s Resident Historian and Editorial Manager. He is a historian of American history and the author of Street Diplomacy: The Politics of Slavery and Freedom in Philadelphia, 1820-1850 (Johns-Hopkins University Press, 2022).