On the morality of chess

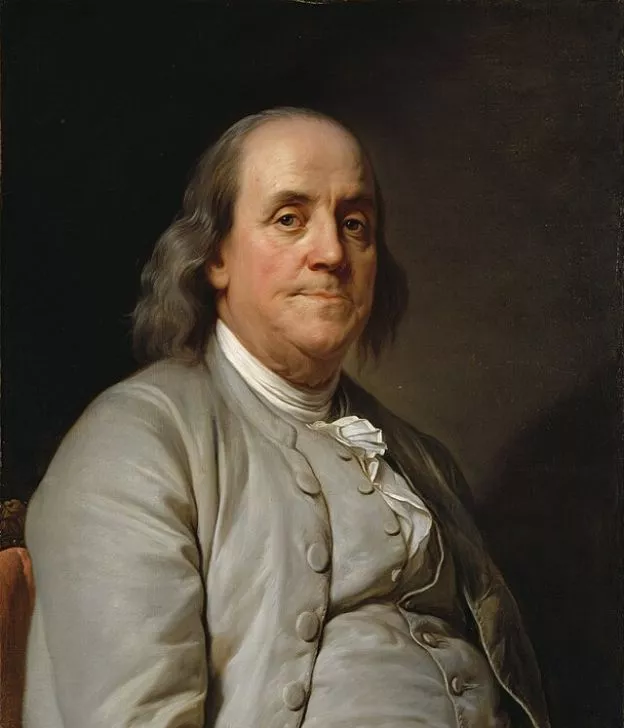

This month we celebrate founder Benjamin Franklin’s 316th birthday.

Four moves

Entrepreneur, philosopher, scientist, inventor, and writer, we ought to add chess master to this list of Franklin’s accomplishments. His essay, “Morals of Chess,” combines his timeless wit, inherent competitiveness, and shrewd strategy that also speaks to the fragile, yet boundless potential of America’s founding principles.

Originally written and presented to Franklin’s small cadre of fellow intellectuals in the 1730s, “Morals of Chess,” would not be released for public consumption until 1786.

Much had occurred over the course of that half century: in 1732 Franklin released the first Poor Richard’s Almanac, an immensely successful guide full of practical advice and witticisms for American colonists; in 1751 he helped found the educational institution that became the University of Pennsylvania; and throughout the 1750s and 1760s he served as the postmaster general for the crown and eventually an agent for the colonies representing American interests in Great Britain. And, of course, by 1776, Franklin and his fellow colonists began (and won!) a war of liberation from Great Britain.

As the colonies’ most recognizable figure, Franklin’s influence became essential to the American cause, especially when he was sent to France as America’s first ambassador in 1776. Franklin’s convivial nature combined with his diplomatic acumen made him the toast of Paris, as he regaled salons with tales, practical wisdom, and Americanisms. And while battlefield realities back in America certainly compelled France to support the American cause, Franklin’s soft diplomacy and charismatic force of personality helped cement the Franco-American alliance. Besides power politics and being playful with his French admirers, Franklin spent much of his five years in France playing chess. While reviewing his personal papers for potential publication in 1779, Franklin came across “Morals of Chess,” which at this point was now over forty years old. Scholars believe that aside from retrieving the material for publication, Franklin was motivated to find this essay due to his indulgence, possibly overindulgence, in playing chess with the Parisian elite.

These games became epic battles that lasted four hours or more, limited solely by the number of candles available to the combatants.

Franklin’s monomaniacal focus made him oblivious to anything outside the checkered board.

Franklin established the edifying purposes of the essay (and one could argue, the game itself) by writing in the first sentence that, “The game of Chess is not merely an idle amusement.” To Franklin, chess instructed individual conduct, and, if played in the proper manner, would teach players four key virtues: foresight, circumspection, caution, and “ the habit of not being discouraged by present bad appearances in the state of our affairs, the habit of hoping for a favourable change, and that of persevering in the search of resources.” Calling chess a “beneficial amusement,” he outlined eight tips so players could “pass the time agreeably,” including observing the rules of the game with fidelity, remaining patient while your opponent plots their next move, and, for spectators, observing “the most perfect silence” to allow for concentration.

However, Franklin’s four key lessons – foresight, circumspection, caution, and perseverance -speak as much to the game of chess as to the political and moral responsibilities of the players on and off the chessboard. In a larger sense, Franklin’s lessons speak to Americans across time and space.

Living in what Americans then and now described as a revolutionary era required foresight: the republican spirit and experiment can only be sustained by those who consider the “consequences that may attend an action.”

Circumspection necessitated a keen observance of the “scene of action,” those relations between chess pieces akin to the various social factions of the American body politic.

Yet Americans must move with caution for “if you touch a piece, you must move it somewhere; if you set it down, you must let it stand.” In other words, Americans must avoid haste to prevent mistakes and steel their resolve once they have made a fateful decision.

Finally, Franklin reminds players, that “supposed insurmountable” difficulties ought not exhaust the player nor precipitate inattention or despair. This powerful idea of a perseverance seeded with hope, reflects striving to form a “more perfect Union.” He urges us to remember that momentary setbacks are precisely that, momentary, and therefore, liable to change if Americans are empowered to cherish those founding principles that inspired the creation of the republic.

On the last day of the Constitutional Convention in 1789, American socialite and political commentator Elizabeth Willing Powel approached Franklin as he left the hall. She asked him, “What have we got, a republic or a monarchy?” As always, Franklin gave her a memorable reply: “A Republic…if you can keep it.” Through their foresight, circumspection, caution, and perseverance, Americans attuned to their nation’s civic needs, perpetuated this republic, the United States of America, by emulating the virtues of Franklin’s “Morals of Chess”.