The steel trap

As the group of men moved stealthily over the undulating Virginia hills, a light breeze in the October night gently wicked the nervous sweat that dampened their brows. Despite the tension, the men clung to one dreamlike hope: freedom for their fellow man.

The highest privilege, & plain duty of man

Two days later, ten of these men would be dead; two months later, in December 1859, seven more would be hung. Why? Because of their ill-fated mission to raid Harpers Ferry, Virginia.

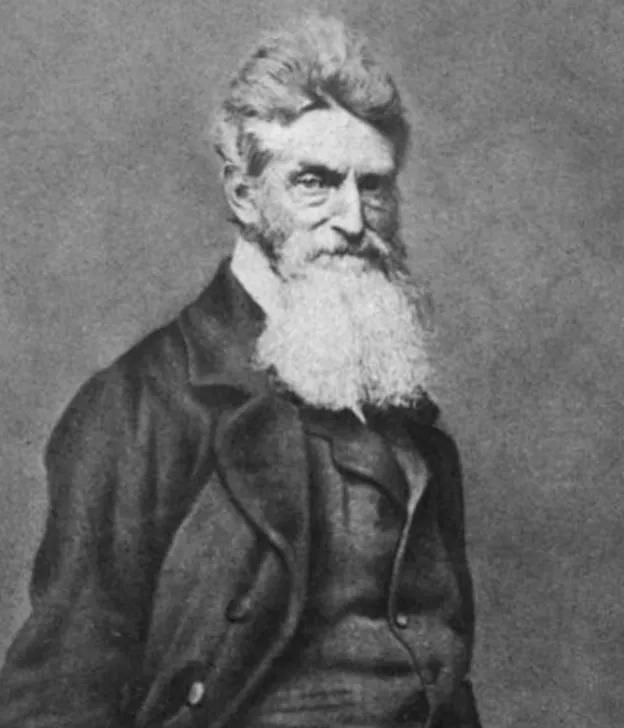

The group’s leader, John Brown, labeled at times a visionary, fanatic, terrorist, hero, fool, and martyr, sought vengeance for the human beings caught in what he called a constant “state of war”: slavery. Though his intentions were pure, Brown’s incessant zeal to liberate Black Americans necessitated, in his mind, carnage and bloodshed. His uncompromising position on liberation derived from a religious fervor as well as his deep-seated love for Black Americans. The latter view set him apart from most whites living during his time.

Sure, white abolitionists displayed their devotion by petitioning the government, publishing newspapers, forming interracial reform societies, and pledging to suffer physical abuse for their beliefs – but would they hatch a massive emancipation scheme and willingly and purposefully kill slaveholders in the process?

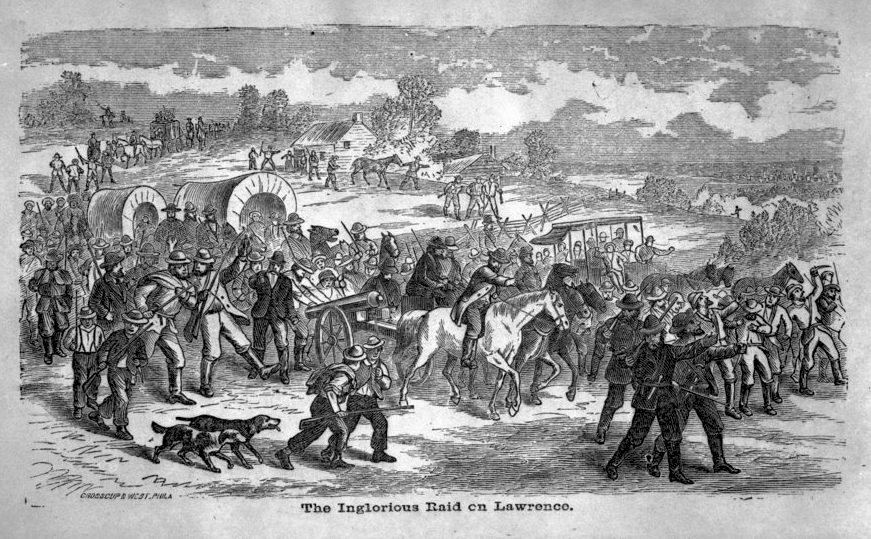

As the United States approached the Civil War, John Brown stood alone in this regard. Unlike the most noteworthy abolitionists of his day, he cut his teeth in the brutal guerilla war known as “Bleeding Kansas.” The Kansas-Nebraska Act passed by Congress in 1854 allowed settlers to vote for whether these new states would welcome or prohibit slavery. Soon waves of “Free-staters” and proslavery settlers rushed into Kansas, ushering in fierce and bloody clashes between the two groups; Brown was, of course, among the wave of Free-staters. In response to the sacking of Lawrence, Kansas by pro-slavery forces and the horrifying caning of Massachusetts Senator Charles Sumner on the Senate floor in 1856, Brown and several others butchered five pro-slavery settlers with their cutlasses at Pottawatomie, Kansas – murders for which he was never punished.

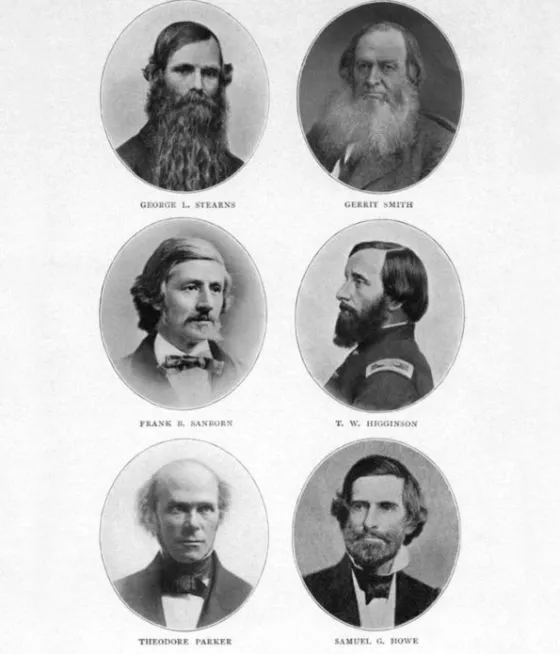

The Secret Six

Such gory realities never appeared to haunt Brown: in fact, they inspired him to continue his war against slavery by soliciting funds from wealthy abolitionists known as the “Secret Six.” Brown convinced these abolitionists that he could execute a series of slave escapes that would facilitate his larger ambition: the “Subterranean Pass-Way.” Not unlike the Underground Railroad, the pass-way would serve as a clandestine path to freedom running through the Allegheny and Appalachian Mountains. If successful, Brown’s vision would allow thousands of Black Americans to escape Southern slavery.

Knowing that these fugitives from slavery would need weapons – thousands of weapons – to defend themselves from slaveholders and their supporters north and south, Brown set his sights on raiding the federal armory at Harpers Ferry, Virginia and distributing them to the enslaved people of the region.

He made his plans known to two crucial Black leaders: Frederick Douglass and Harriet Tubman. Douglass and Brown met multiple times throughout the late 1850s, with Brown even living with Douglass for a month in early 1858. The last time they met they did so secretly in an old rock quarry in Chambersburg, Pennsylvania, about three weeks before the raid. While Douglass admired Brown’s gumption, he expressed wariness regarding his plans, telling Brown that frankly, he “was going into a perfect steel trap, and that he would not get out alive.” Tubman, who Brown called “one of the best and bravest persons on the continent” and whose work with the Underground Railroad he hoped to emulate on a much larger scale, helped raise money for Brown in the spring and summer of 1859 – but she, too, had her doubts, and declined Brown’s offer to participate in the raid.

Despite these setbacks, using the funds secured from the Secret Six Brown purchased 200 rifles and thousands of pikes (long-wooden poles with sharpened steel points) with which he planned to arm the enslaved people in Virginia and precipitate a major rebellion. This massive flight of the enslaved with have not only a crippling effect on the southern economy, but it would also strike fear into the hearts of slaveholders who barely a generation earlier crushed Nat Turner’s rebellion. Brown hoped that his raid on Harpers Ferry would inspire more enslaved people from the surrounding states to join the ranks of his liberation force.

In the months leading up to the raid, Brown and 21 other men holed-up in Kennedy Farm, about five-miles north of Harpers Ferry. Among Brown’s men were three of his sons, Oliver, Owen, and Watson as well as five men of color, including the man who would become the sole Black survivor, Osborne P. Anderson, who later wrote the only firsthand account of the raid. To Anderson, Brown was “chosen by God” to become a new Moses and help lead the enslaved to freedom. But what Anderson most admired about Brown was his empathy for the oppressed. In his words,

John Brown, the liberator of Kansas, the projector and commander of the Harper’s Ferry expedition, saw in the most degraded slave a man and a brother, whose appeal for his God-ordained rights no one should disregard.

Shortly after arriving at Kennedy Farm, Brown penned his own version of the Declaration of Independence, which he believed justified his right to embark upon a slave revolution. Entitled “A Declaration of Liberty by the Representatives of the Slave Population of the United States of America,” Brown modified the self-evident truths enshrined in the original document, stating

We hold this truth to be self evident; That it is the highest Privilege, & Plain Duty of Man; to strive in every reasonable way, to promote the Happiness, Mental, Moral, & Physical, elevation of his fellow Man.

Brown spotlighted the innumerable grim consequences of enslavement throughout his version of the Declaration, as well as a salient portent: he promised to obtain the right to liberty “or die in the struggle.”

Brown and his men cautiously yet meticulously cased Harpers Ferry from July through October 1859: they identified the telegraph wires they needed to cut, surveyed the bridges and building they needed to capture, and plotted the best means of egress so that they could funnel out of the city and spread the rebellion across the Old Dominion.

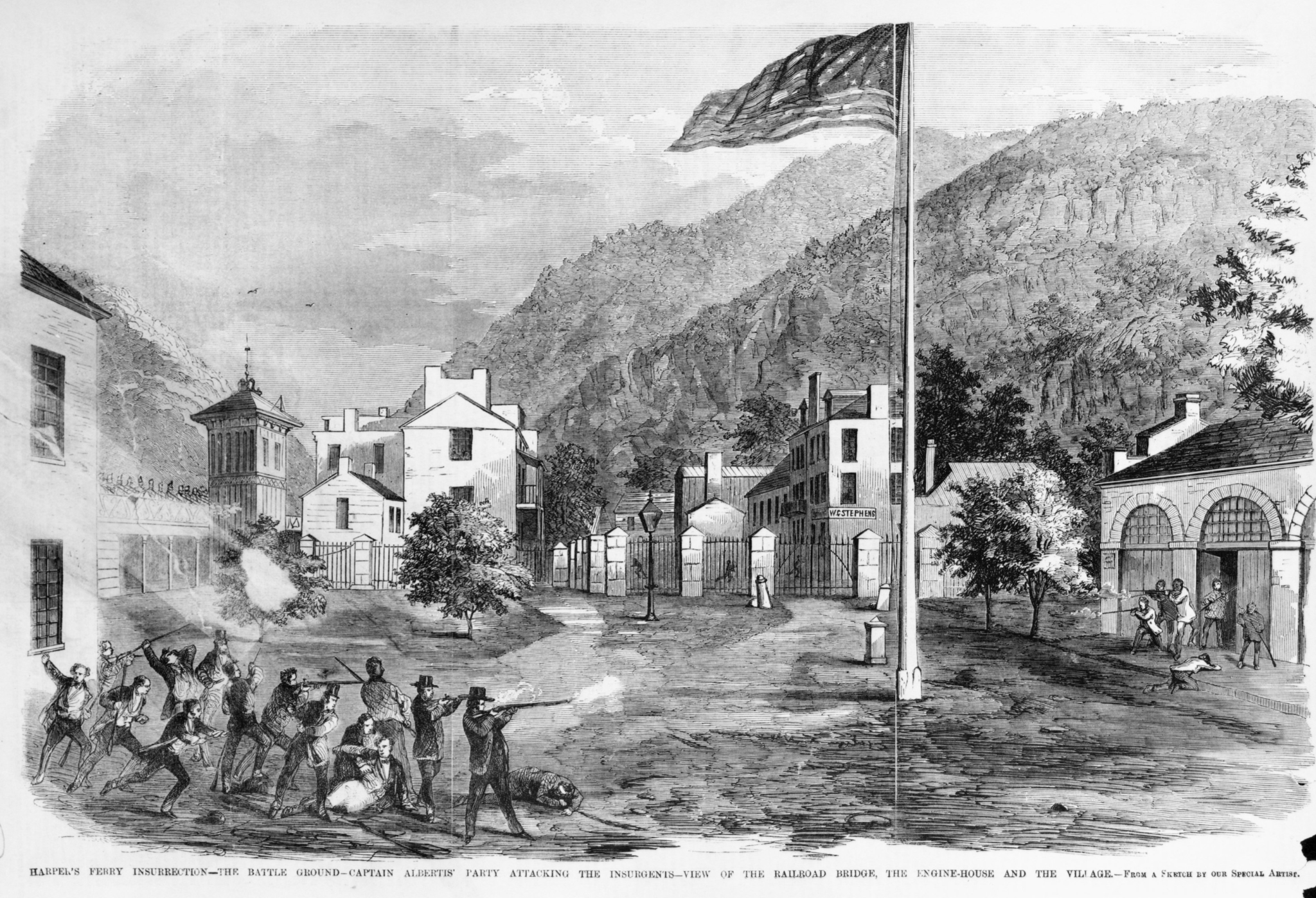

Returning to the damp and chilly night march toward Harpers Ferry on October 16th, 1859, Brown and his heavily armed soldiers departed from Kennedy Farm at 8pm, walking in pairs first through the field and along the road leading to the town. The first stage of the raid almost went as planned: they seized both bridges leading into town, cut the telegraph lines, captured the railroad station, the armory, and the rifle works, and took white slaveholders and their slaves hostage, including Lewis Washington, George Washington’s great-grandnephew. Brown boldly told his first hostages, “I want to free all the negroes in this state…if the citizens interfere with me, I must only burn the town and have blood.” Of course, seizing bridges, capturing buildings, and taking hostages was one thing – but holding them without arousing suspicion was another thing entirely.

A free Black baggage master and railroad employee named Heyward Shepherd saw a train stop at one of the captured bridges and went to investigate. When they ordered him to halt, Shepherd ran, and they opened fire, mortally wounding him. In the words of the historian Tony Horwitz, “Brown’s campaign to liberate slaves claimed as its first casualty a free black man.”

The next 30 hours were a whirlwind of events.

Shepherd’s shooting raised the alarm across Harpers Ferry, prompting messengers to bring word of a slave rebellion to the surrounding towns.

The townspeople surrounded the armory’s engine house containing Brown, his men, and their hostages; both sides exchanged fire, resulting in the deaths of one of Brown’s men and a local grocer.

The next 30 hours were a whirlwind of events. Shepherd’s shooting raised the alarm across Harpers Ferry, prompting messengers to bring word of a slave rebellion to the surrounding towns. The townspeople surrounded the armory’s engine house containing Brown, his men, and their hostages; both sides exchanged fire, resulting in the deaths of one of Brown’s men and a local grocer. The situation steadily worsened: residents honored a flag of truce from Brown’s ally William Thompson, but when the mayor of Harpers Ferry was killed in the crossfire, the enraged townspeople savagely beat Thompson and then executed him. Consequently, two more of Brown’s men were shot while flying a white flag; other raiders attempted to escape only to be shot down by the townspeople, their bodies later used as target practice.

The local militia had set the steel trap that Frederick Douglass warned of, and by 11pm on October 17th, Colonel Robert E. Lee and 90 United States Marines had arrived from Washington, D.C. Lee assigned Lieutenant J.E.B Stuart to negotiate Brown’s surrender and if he refused, to storm the raiders.

Brown refused, Stuart wrote, so “I left & I waved my cap & the plan was carried out.” The Marines rushed the engine house and captured Brown and four other raiders.

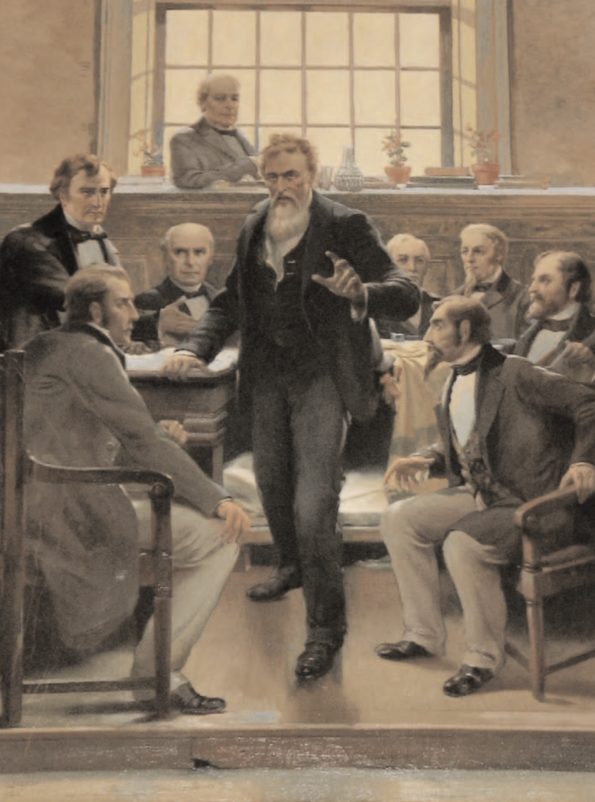

Two weeks later, the state of Virginia sentenced John Brown and the surviving raiders to death. When asked if he had anything to say in his defense, Brown delivered a short speech filled with the abolitionist zeal that synthesized the various labels given him, from visionary to fanatic to hero:

The court acknowledges, as I suppose, the validity of the law of God. I see a book kissed here which I suppose to be the Bible, or at least the New Testament. That teaches me that all things whatsoever I would that men should do to me, I should do even so to them. It teaches me further to “remember them that are in bonds, as bound with them.” I endeavored to act up to that instruction. I say, I am too young to understand that God is any respecter of persons. I believe that to have interfered as I have done — as I have always freely admitted I have done — in behalf of His despised poor, was not wrong, but right. Now if it is deemed necessary that I should forfeit my life for the furtherance of the ends of justice, and mingle my blood further with the blood of my children and with the blood of millions in this slave country whose rights are disregarded by wicked, cruel, and unjust enactments. — I submit; so let it be done!

As the Civil War would prove, John Brown’s vision of emancipation required bloodshed. While politicians of every stripe sought compromise, conservatism, or indifference when it came to the question of slavery, it was clear that slavery would not fade away on its own.

The fanatic means by which Brown thrust abolition into public discourse primed Americans, especially northerners, to remedy the innate evils of slavery. Northerners, led by Abraham Lincoln, helped set in motion the gears of war that at first enforced the non-extension and then complete abolition of slavery. This heroic effort undertaken by white and Black Union soldiers saved the Union on terms that would make it worth saving, not least of all because of the founding ideals espoused by Americans throughout the centuries.

This post was also featured on RealClear History.

Elliott Drago serves as the JMC’s Editorial Officer. He is a historian of American history and the author of Street Diplomacy: The Politics of Slavery and Freedom in Philadelphia, 1820-1850 (Johns-Hopkins University Press, 2022).