The Fort Stevens incident

The Battle of Fort Stevens, or, the moral turning point of the Civil War?

You shall reap a great reward

The unforgiving heat spilled over the brim of his stovepipe hat…

The roughhewn parapet beneath his sweaty hand as he leaned over to catch sight of the men in gray…

A bullet shrieked through the air and struck the man beside him…

…what happened next to Abraham Lincoln remains a source of speculation.

Some say Union General Horatio Wright, the man who invited Lincoln to view the fighting on that very parapet, therefore exposing him to enemy fire, “asked him to withdraw, which Lincoln did only after an officer standing near him had been wounded.”

Others say that a young Union officer and future Supreme Court Justice named Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr. manhandled Lincoln and shouted, “Get down, you damn fool!”

However it happened, and whoever grabbed Lincoln, one thing was for sure: on that day, July 12th, 1864, Abraham Lincoln became the first – and only – sitting President to come under direct and purposeful* fire from an enemy soldier. The site of this incident occurred on the parapet of Fort Stevens, located five miles north of the White House.

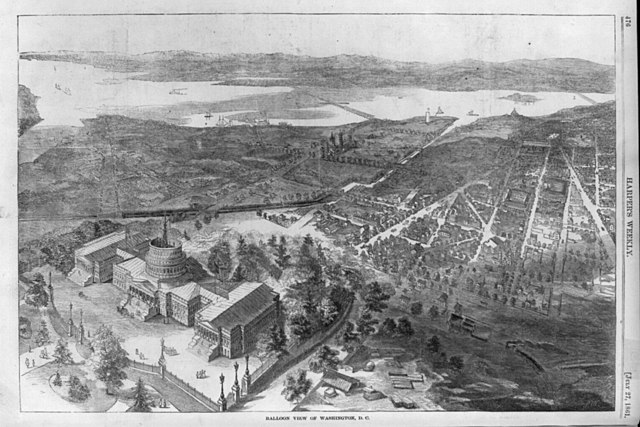

Fort Stevens was one of 68 forts that comprised a 37-mile defensive ring around the nation’s capital. Originally known as “Fort Massachusetts” and later renamed Fort Stevens in honor of Brig. Gen. Isaac Ingalls Stevens, killed at the Battle of Chantilly in 1862, the fort was built on land owned by the family of Elizabeth Thomas, a free Black woman. The Union army requisitioned her property in September 1861, and by 1862, constructed resilient yet humble earthworks featuring 19 cannons and surrounded by a wooden parapet approximately four feet high.

President Abraham Lincoln visited this fort on July 12, 1864, to witness the second day of skirmishing that became known as the “Battle of Fort Stevens.” A month earlier, Confederate commander Robert E. Lee had sent Lieutenant General Jubal Early on a terrifying raid through the Shenandoah Valley as a last-ditch attempt to disrupt the Union supply chain and weaken Northern morale, especially in border state Maryland.

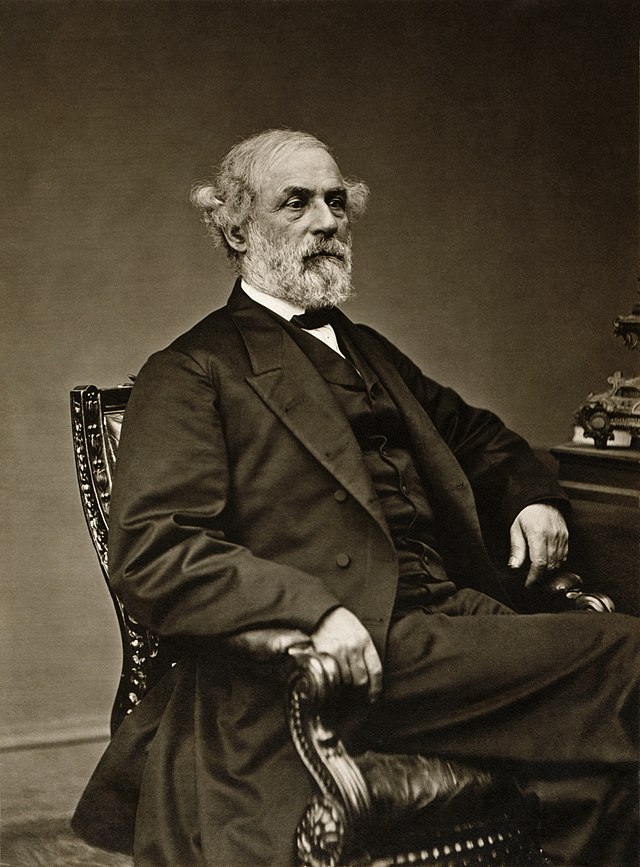

Lee nicknamed Early (left) his “bad old man,” and Early lived up to this moniker: between leaving Richmond on June 13th and arriving at Fort Stevens on July 11th, Early defeated two Union Generals and captured and ransomed both Hagerstown and Frederick, Maryland, with more wary border state communities in his sights. From there, Early set his sights on an even more ambitious objective: capturing Washington, D.C.

It would be hard to understate the consequences of Early raiding and then capturing the nation’s capital, and speculations abounded. Would the Union have to sue for peace? Would Early raze the city? Would European powers throw their weight behind the Confederacy? Would Lincoln escape, and if he didn’t, what fate would await him as a Confederate prisoner of war?

The citizens of Washington, D.C., were nothing short of horrified at these prospects. According to the journalist Noah Brooks:

The city is in a ferment; men are marching to and fro; able-bodied citizens are gobbled up and put in the District militia; refugees come flying in from the country, bringing their household goods with them; nobody is permitted to go out on the Maryland roads without a pass, and at every turn an inquiring newspaper correspondent is met by some valiant in shoulder straps, pompous and big with importance, in the rear of all danger, with ‘By what authority are you here, sir?’

Lincoln’s personal bodyguard, Sergeant Smith Stimmel, noted bluntly that “The 11th of July was an anxious day for the President, and for all who knew the situation.”

Stimmel and the rest of Lincoln’s bodyguards accompanied the President the next day when he went to greet soldiers from the Union VI Corps disembarking from ships on the Potomac River. Led by General Horatio Wright (right), the VI Corps inspired confidence in Lincoln and many Washington residents, as these battle-hardened soldiers recently saw action at the Battle of Cold Harbor in June. Now tasked with defending Washington, the Sixth Corps headed to Fort Stevens with Lincoln and his bodyguards.

The President well-understood the value of his embarking to Fort Stevens. The historian Charles Bracelen Flood wrote “It became a remarkable scene: the commander-in-chief at the head of his marching soldiers and a great crowd of civilians, all headed out of the city along a wooded road toward the thunderclaps of cannon fire from an artillery duel already underway.” An encouraging sight to be sure, and so despite risking the Union and his own life, Lincoln made a “bee-line” to Fort Stevens and arrived ahead of the entire Sixth Corps.

And here we find the origin of multiple accounts explaining what happened to Lincoln on the parapet.

According to a Union soldier named David T. Bull, “Old Abe and his doctor” (and Mrs. Lincoln!) stood on the parapet when a Confederate sharpshooter shot and wounded the doctor. “Old Abe ordered our men to fall back,” according to this soldier. The Lincoln expert Matthew Pinsker explained that Bull erred as it was an assistant surgeon named Crawford from the 102nd Pennsylvania Volunteers who was wounded.

Oliver Wendell Holmes’ story from above also does not pass muster, as he failed to mention his version of events the next day, a day which he spent with both of Lincoln’s secretaries.

General Horatio Wright’s story was confirmed by another Union soldier named Peter Kaiser, who stated that Wright told Lincoln that the president “was too conspicuous an object to remain in so exposed a position.” Regardless of how it happened and who grabbed him, Lincoln experienced a Civil War battle zone firsthand, and after the incident, plopped himself down in the shade under the parapet. The Union carried the battle of Fort Stevens, ultimately driving off Early’s forces and preventing the capture of Washington, D.C.

Did you know?

However, while a mere skirmish in the grand drama of the war, Early’s attempted raid of the nation’s capital proved that the Confederacy might be reeling but not beaten. Lincoln’s experience at Fort Stevens and the subsequent defense of the capital dissipated much of his anxiety. One of Lincoln’s closest friends and confidantes, Orville Browning, recorded in his diary “The President is in very good feather this evening [July 12]. He seems not in the least concerned about the safety of Washington. With him the only concern seems to be whether we can bag or destroy this force in our front.” As the historian James McPherson asserted, Lincoln knew better than most of his generals that with the “by the literal or substantial destruction of Lee’s army, the rebellion will be over.” The failure to give chase to Early therefore prolonged the war for another year.

Fast-forward to a blustery November day in 1911. 200 people gathered to dedicate a memorial to the spot where Lincoln came under fire at Fort Stevens. The memorial itself consisted of “a huge, rugged boulder, emblematic of the character of the great war President,” and taken from the grounds of nearby Walter Reed Hospital, where Confederate forces amassed to attack the fort. And while most of this post has focused on the story of Lincoln almost getting shot, we forget an even more legendary tale, that of the lone Confederate sharpshooter who climbed a tall tulip poplar on those same grounds to shoot Lincoln, recognizable by his stovetop hat. Lightning struck this tree in December 1920, later referred to as the “tree that almost brought down a presidency.”

The 1911 commemoration featured several speakers, including William V. Cox, president of the Fort Stevens Association, former Confederate General Floyd King, who served under Jubal Early, and Union Colonel John McElroy, who served as a “commander” in the vaunted Union veteran organization called the “Grand Army of the Republic.”

Cox told the audience that his association continued to make progress toward their goal of making the fort a “military park,” i.e., a national park. However, he lamented that the “rugged boulder” was not enough to memorialize Lincoln and the “brave boys” who fought and died there. Cox believed that Fort Stevens ought to serve as the site of the much-debated Lincoln Memorial. Unfortunately, in 1915 workers broke ground on the Lincoln Memorial in a location described by Cox as being “in the lowlands of the Potomac, where Lincoln never was and could not have gotten, even with rubber boots…”

Floyd King’s keynote speech expressed historical revisionism as well as reconciliation. He spoke highly of Lincoln and explained that he and his fellow Confederates fought against him not because they disliked him, “but because each felt his theory of government was correct, and that it was his honored right to defend his cause.” While Americans today should find such a remark troubling – King’s “cause” meant the right to enslave human beings, after all – keep in mind that King served under Jubal Early, one of the most vociferous proponents of the mythical “Lost Cause.”

This myth attributed Confederate defeat to overwhelming Union resources and casted the Confederacy’s “cause” as noble by downplaying the savagery of Southern slavery. King then assured the crowd of his patriotism, explaining that he and other Confederate veterans “bent with age” would defend Old Glory and “shed their blood as freely as they did in the days of the civil war.”

While we lack the full text of Colonel John McElroy’s speech, we know that he entitled it “Fort Stevens, the Moral Turning Point of the War” and recommended emblazoning those words on the memorial boulder (which lacked an official plaque until 1920). The title alone should give us pause, as most Civil War aficionados would not rank the battle of Fort Stevens as significant a turning point as say, the Emancipation Proclamation, Gettysburg, or the Election of 1864. What exactly did McElroy mean by “moral turning point”? In a word: confidence.

First, McElroy argued that prior to the battle, the value of government-backed paper dollar had shrunk to 35-cents. After the battle, the dollar bounced to 48-cents and kept rising throughout the war. Hence, the battle inspired Americans’ confidence in the Union economy.

Second, McElroy described the “dismay” and panic felt by Northerners, especially those living in the environs of Washington, D.C., who heard of Early’s approach. Many Northerners believed that the capital would fall to Early and usher in European support for the Confederacy, thus sealing the fate of the Union. However, the Union victory at Fort Stevens allayed Northerner’s fears and helped inspire the political confidence to reelect Lincoln in November 1864.

Finally, McElroy addressed the ultimate, moral confidence that Fort Stevens symbolized for the Union cause. A Senate aide named Fred L. Fishback paraphrased this crucial point in an article he wrote for the Boston-based National Magazine in January 1912:

The soldiers of the North, while fighting for the preservation of the Union, always had on their hearts the capital of their country, and they fought that the government might live. It was the concrete object of their devotion.

Like many Americans then and now, the Civil War was a moral crusade, and McElroy channeled that sentiment when he appealed to the war’s moral turning point at Fort Stevens. After all, this Union victory foreclosed a consequential “what if” of history, namely, what if that Confederate sharpshooter had shot and killed Lincoln? No Lincoln, no Lincoln victory in 1864 presidential election. No second term for Lincoln, no second inaugural address from Lincoln. Might we say, too, that no Lincoln meant no Union?

Today, Fort Stevens remains a humble earthwork that once hosted the only moment in US history in which a sitting President faced direct and purposeful* gunfire from an enemy. While Cox et al. did not get their wish of having the fort serve as the site of the Lincoln Memorial, the stories that grew out of that fateful day in July 1864 have become woven into the timeless tapestry of American history.

But wait a minute, what about Elizabeth Thomas, the free Black owner of the property upon which Union soldiers built Fort Stevens in 1861? Certainly, she deserves the last word!

This construction effort demolished Thomas’ home and barn and destroyed her orchard and garden. The basement of where her home once stood became the location of the fort’s powder magazine and a small cabin on the property became the officers’ quarters. Thomas wept and held her six-month old baby as she watched the Union troops tear through her home. As she sat crying under a sycamore tree, a “tall, slender man dressed in black” appeared before her. The man consoled her and said, “It is hard, but you shall reap a great reward.” That man, of course, was President Lincoln.

Elizabeth Thomas also attended the 1911 ceremony, in fact, and can be seen sitting next to the speakers. Although she did not make a speech herself, a reporter for the Washington Times wrote that Thomas recounted seeing Lincoln “many times” during the fight. In fact, according to an article written about her in 1952, when Thomas heard of Lincoln’s arrival, she retrieved her old shotgun “to kill any “Rebs” who would try to kill Lincoln.” But before she could shoot any “Rebs”, Elizabeth Thomas performed perhaps the most critical act in American history:

“Suddenly, she looked out of the window and saw Lincoln standing on a bank of a newly built trench. Dropping everything, she yelled to the soldiers standing near him, “My God, make that fool get down off that hill and come in here.”

History and memory are fickle yet unavoidable bedfellows. Many people claimed to have saved Lincoln that day: ordinary soldiers, a general, a future Supreme Court justice, and of course, a free woman of color. When faced with this selection of potential Lincoln saviors, I must go with Elizabeth Thomas: the “great reward” promised her by Lincoln may have been her saving his life and thus, saving the nation we live in today.

This post was also featured on RealClear History.

Elliott Drago serves as the JMC’s Editorial Officer. He is a historian of American history and the author of Street Diplomacy: The Politics of Slavery and Freedom in Philadelphia, 1820-1850 (Johns-Hopkins University Press, 2022).