The Birthday Dinner

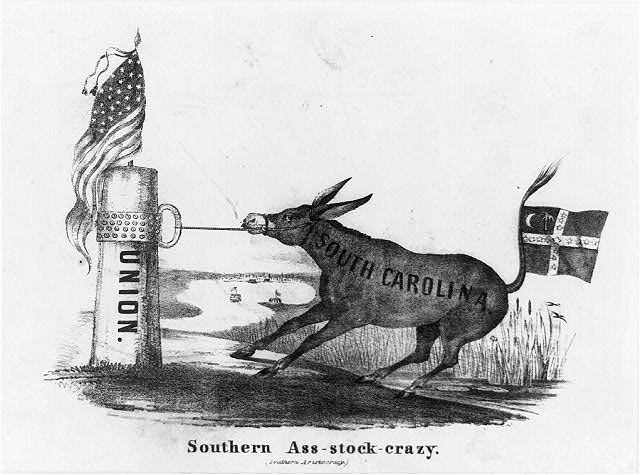

Andrew Jackson throws the gauntlet of Union.

Next to our liberty, most dear?

Andrew Jackson enjoyed dueling.

But rather than focus on his famous gunfights, we might take a closer look at a political duel he fought with the man who served as his vice president and nemesis, John C. Calhoun.

The setting was not a windswept prairie, a dusty crossroad, nor a vacant lot. Instead, Jackson and Calhoun dueled during a dinner honoring Thomas Jefferson’s birthday.

This dueling of minds had roots in early arguments over states’ rights, the power of the federal government, and the founder’s intentions for the American republic. In fact, the origin of the Jackson-Calhoun intellectual duel lay within the founding generation.

Mired in a quasi-war with France in 1798, John Adams’ administration passed the infamous Alien and Sedition Act, which threatened Adams’ opponents with arrest, imprisonment, and even deportation if they spoke out against his administration.

Thomas Jefferson and James Madison both issued strong rebukes in response, now known as the Kentucky and Virginia Resolutions. The Kentucky Resolution, written by Jefferson, argued that individual states could declare void, or nullify, federal laws offensive to their interests. Madison, writer of the Virginia Resolution, stated that states could insert themselves between the federal government and the people, or “interpose, for arresting the progress of the evil” federal laws they considered unconstitutional. Both concepts, nullification and interposition, became the basis of states’ rights doctrine.

Carolinian John C. Calhoun first championed nullification anonymously in response to the so-called “tariff of abominations” passed by Congress in 1828. This tariff favored northern manufacturers to the detriment of the South, who relied on imports from Europe. While many southerners abhorred the tariff, few were willing to claim that individual states had the power to nullify federal law. Instead, according to the historian William W. Freehling, this moderate majority of southerners, many of whom supported and adored Jackson, believed that they could solve the problem of the tariff by using congressional means to pass a new, less burdensome tariff.

John C. Calhoun would have none of that

He despised the tariff, and firmly believed that nullification was the solution to the federal government imposing the interests of one section of the country onto another. His state’s cotton-growing planter class claimed that “forty bales” out of every hundred were lost to the tariff, and over time, such an imposition would cause the cotton economy to collapse. Since the price of cotton was directly commensurate with the price of enslaved people, the destruction of the cotton economy would bankrupt slaveholders whose entire fortunes were tied up in the inextricable wealth of cotton and the enslaved. These slaveholders did not want to rely on new legislation to protect their wealth, especially when South Carolina’s enslaved population outnumbered the white population.

Thus, in the words of the historian Sean Wilentz, slaveholders feared as much for their wealth as for their lives, seeing how the tariff “was but a means to effect ‘the abolition of slavery throughout the southern states,” even predicting a race war if abolition occurred: these prophecies lay at the heart of the “abominable” effects of the tariff.

In December 1828, then-vice president Calhoun wrote the The South Carolina Exposition and Protest, in which he stated that South Carolina possessed the power to nullify the Tariff of 1828. After explaining how the tariff advanced northern manufacturing interests at the expense of the agricultural interests in the South, Calhoun went on to reinterpret the founding of the country. He argued that while the federal government and the states shared some powers, ultimately, the federal government and Constitution were a creation of the states, and therefore, states remained the final, sovereign arbiter of determining whether a federal law was constitutional. To nullify laws they viewed as unconstitutional, Calhoun recommended that states hold conventions through which “effectual protection is afforded to the minority against the oppression of the absolute majority.” With Andrew Jackson’s inauguration on the horizon, Calhoun also wrote of the hope that “this eminent citizen” would restore the “pure principles of our government.”

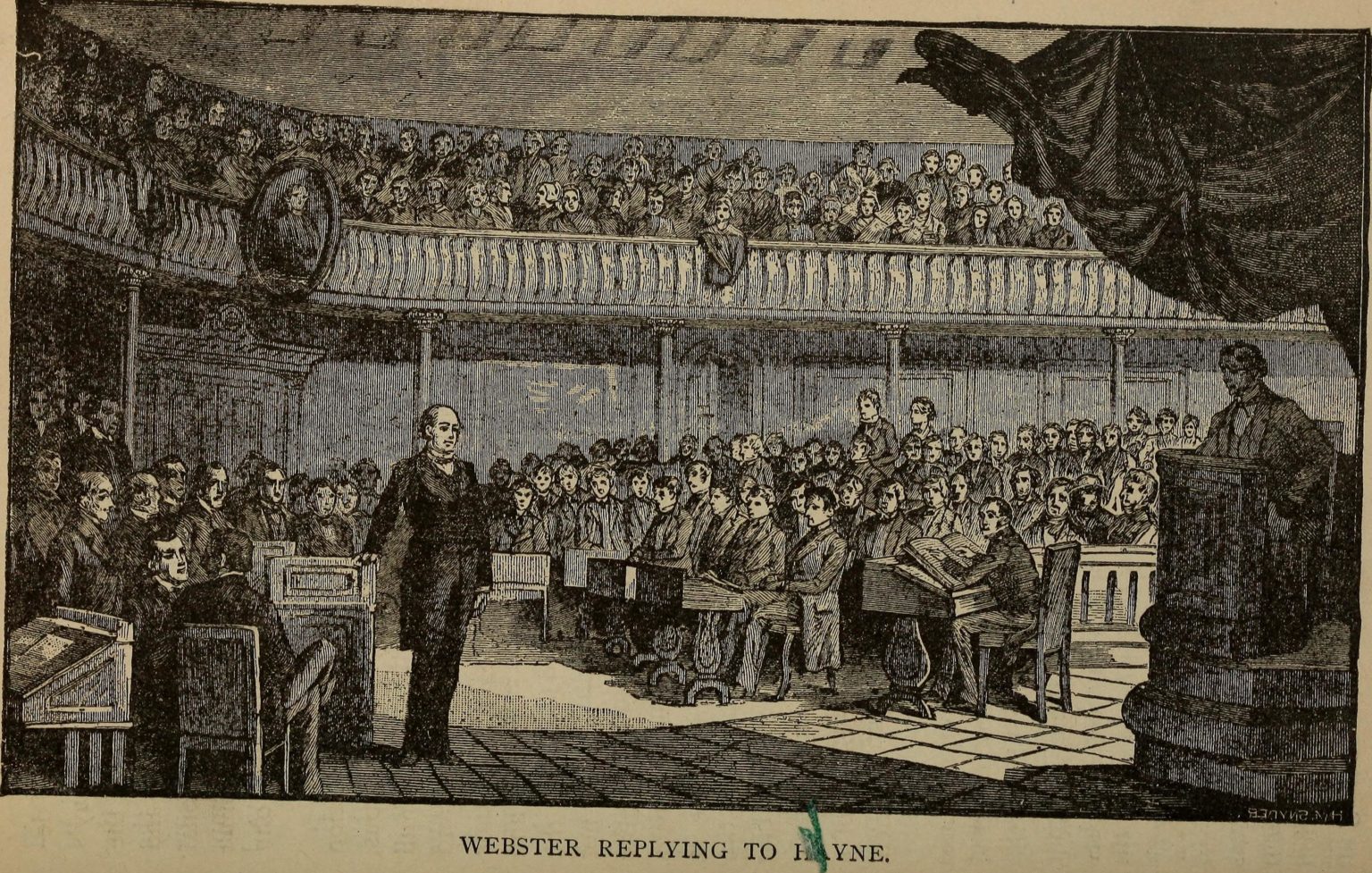

Calhoun could not have been more wrong. Between the Exposition’s publication and the Jefferson Birthday dinner, Senate powerhouses Daniel Webster of Massachusetts and Robert Hayne of South Carolina debated the matter in early 1830. What began as a debate over whether the federal government should decrease the sale of public land, soon became an argument over nullification. As a Calhoun acolyte, Hayne argued that states had the right to nullify federal laws they judged unconstitutional to protect their citizens. Webster responded that only the Supreme Court had the power to decide the constitutionality of a law. Nullification was heresy at best and treason at worst as it suggested that state sovereignty trumped federal supremacy, which could only lead to chaos. The states did not form a compact known as the Constitution, Webster argued: the states represented a national union of the American people.

Three months after the Webster and Hayne debates, Jackson, Calhoun, and other Washington notables gathered for a dinner celebrating Thomas Jefferson’s birthday on April 13th, 1830. Robert Payne himself helped organize the event, soliciting no fewer than 24 toasts prior to the dinner, but the attendees had no idea that the event would result in a failure on multiple levels.

The first failure involved the Pennsylvania invitees, who “seceded” upon seeing the list of toasts, which they considered too much in the “party” (i.e., partisan) spirit, one that reeked of southern interests. Toasts included unabashed devotions to states’ rights, such as “the support of the State Governments in all their rights” as well as “the bane of the Union: oppression of minorities; unequal taxation; unequal distribution of public benefits.” Senator Hayne lamented during his toast how South Carolina’s position on the tariff had been “misrepresented, and her position reviled” while the 20th toast of the night stated plainly “the States: Their harmony, and overruling consideration in the minds of all patriotic statesmen.”

This paradoxical toast attempted to reconcile the sovereignty of the states with the supremacy of the Union, though it was evident that it leaned more toward the former to the expense of the latter.

President Jackson sat through these toasts, a quiet rage building inside of him. The now-open secret of Calhoun’s authorship of the treacherous South Carolina Exposition, the insolence of the states’ rights advocate’s toasts, and their presumptuous attempt to hijack Jefferson’s birthday to justify nullification: all of it disgusted Jackson. So began the duel and the second historical failure of the evening.

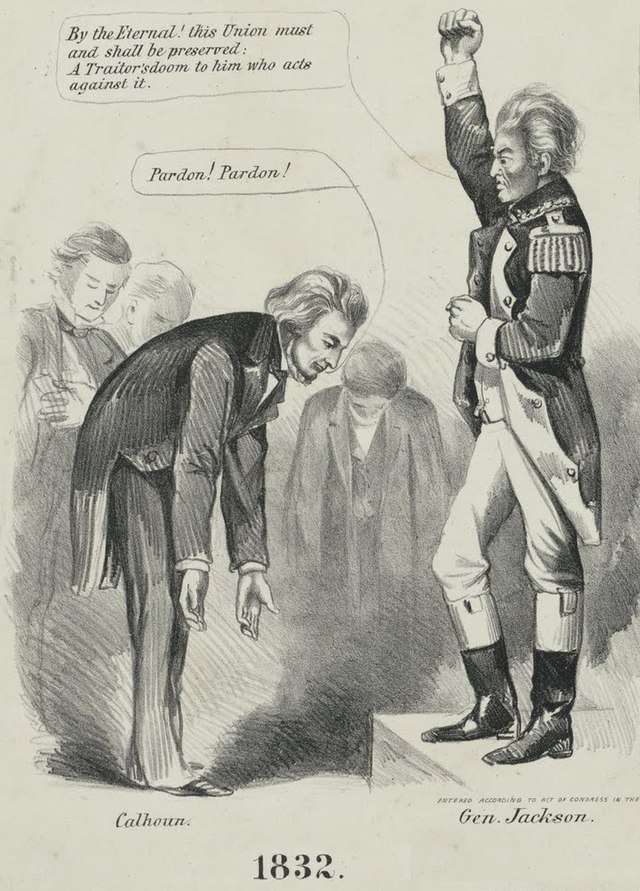

With calm forbearance, Jackson obliged the master of ceremonies when calling for volunteer toasts. Raising his glass and staring directly into the eyes of Vice President John C. Calhoun, he said:

Our Federal Union: It must be preserved.

This pithy toast spoke to Jackson’s commitment to the national Union of the American people, one that ought not be trampled underfoot by the wants of individual states. He underscored his love of Union a few years later during the Nullification Crisis of 1832-1833, in which Calhoun and South Carolina made the fateful decision to convene and approve an “Ordinance of Nullification.” This ordinance sought to nullify the 1828 tariff and an 1832 tariff, the latter of which was a compromise measure that decreased the economic burden on the South. The nullifiers disagreed, arguing that the tariffs were “unauthorized by the Constitution of the United States, and violate the true meaning and intent thereof, and are null, void, and no law, nor binding upon this state.”

In 1832, Jackson responded to the nullifiers with one of the boldest proclamations made by any president. “Strict duty” required Jackson to execute the Constitution to preserve the Union, a Union forged during the Revolution, a Union whose sole purpose was to unite the states in “common interest” and not the “impractical absurdity” of a single state defying the others. But Jackson went further:

I consider, then, the power to annul a law of the United States, assumed by one State, incompatible with the existence of the Union, contradicted expressly by the letter of the Constitution, unauthorized by its spirit, inconsistent with every principle on which it was founded, and destructive of the great object far which it was formed.

He strengthened this point by referencing his own heritage as a South Carolinian: even as a native of that state, he knew to put the common good of the Union above the specific good of his home state. Jackson frankly addressed the biggest problem: South Carolina’s nullification project brought the state to the “brink of insurrection and treason.”

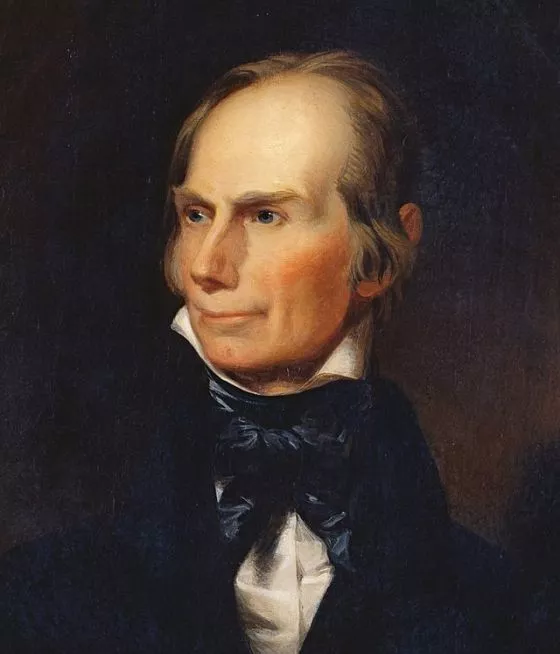

In early 1833 Jackson encouraged Congress to push through the Force Bill, which would authorize the Commander-in-Chief to use military force to collect the tariff from South Carolina. This extreme action was averted through the politicking of Henry Clay, who, while certainly no friend of Jackson nor Calhoun, brokered a compromise tariff with Calhoun. Both the “Force Bill” and the Compromise Tariff passed the same day, allowing for Jackson’s executive power as commander-in-chief to stand, yet also assuaging the tariff imbroglio by allowing another federal branch, Congress, to dictate the reduction in tariff rates.

While nullifiers in South Carolina convened a week later to nullify the Force Bill, an even more dangerous seed was planted in the minds of at least some southerners: nullification was no longer a live option within the union. Therefore, less than a generation later, their perceived last resort became a pillar of the Confederacy’s political philosophy: the right to secede.

Returning to the Jefferson Birthday Dinner, Jackson’s love of union was met with a response from Calhoun that became prophetic. Lacking the flair of Jackson’s immortal words, yet nonetheless, portending the outbreak of the Civil War, Calhoun’s toast followed:

The Union: Next to our liberty, most dear; may we all remember that it can only be preserved by respecting the rights of the states and distributing equally the benefit and burden of the Union.

In the coming decades, southerners who defined their ‘liberty’ through the enslavement of human beings made good on Calhoun’s words and would wage a brutal war for slavery that resulted in the deaths of over 750,000 Americans. However, President Abraham Lincoln made good on Jackson’s words, sending troops into the South to reclaim not so much territory or even property, but in fact, reclaim a new birth of freedom for the United States of America, a union “of the people, by the people, and for the people.”

Elliott Drago serves as the JMC’s Editorial Officer. He is a historian of American history and the author of Street Diplomacy: The Politics of Slavery and Freedom in Philadelphia, 1820-1850 (Johns-Hopkins University Press, 2022).