Juneteenth

On June 19th, we celebrate Juneteenth and the end of slavery in the United States.

The Road to and from Emancipation

Today we celebrate Juneteenth and the end of slavery in the United States. While this is only the third time it has been celebrated as a national holiday, the occasion has been celebrated in the African American community for over 150 years.

But what is the history behind Juneteenth and the journey to freedom for all?

Many Americans think that slavery ended in the United States when President Abraham Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863, a document which declared that “all persons held as slaves” within the rebellious states “are, and henceforward shall be free.”

But in reality, the path to realizing freedom was much more complicated.

Fearing the loss of Americans who remained loyal to the Union, Lincoln’s Proclamation did not emancipate enslaved people in certain parishes in Louisiana as well as the states of Maryland, Missouri, Tennessee, and West Virginia, though each of those states abolished slavery before the war’s end.

In fact, news of the proclamation did not reach all enslaved people at the same time, with some African Americans first hearing about emancipation months after the war ended in April 1865.

Proclaiming Emancipation

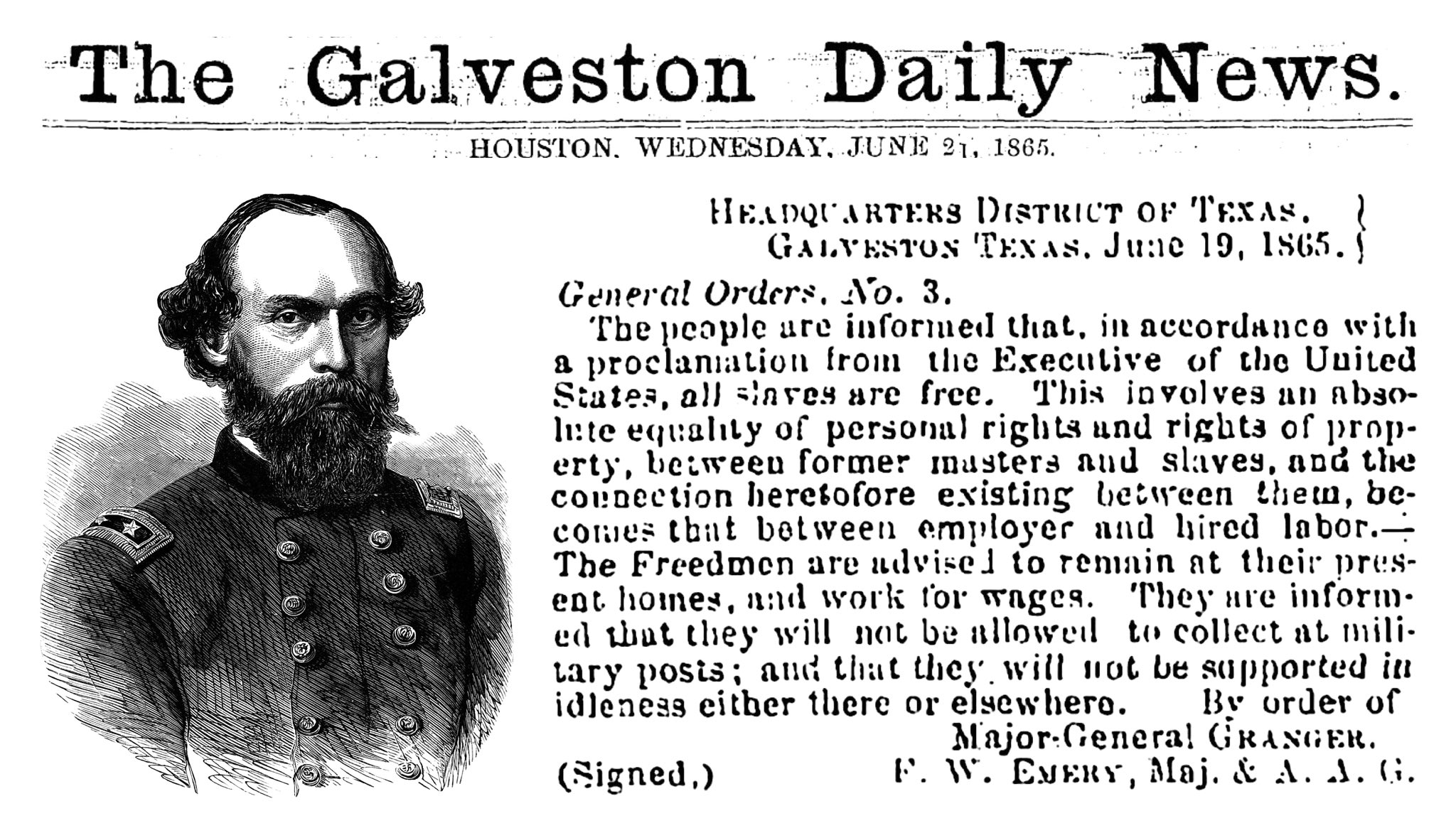

Union troops under the command of Major General Gordon Granger arrived in Galveston, Texas on June 19th, 1865, the final place yet to be notified.

Granger and his men went street-to-street proclaiming “The people of Texas are informed that, in accordance with a Proclamation from the Executive of the United States, all slaves are free.”

Between 1936 and 1938 the Federal Writers’ Project conducted interviews with 2,300 former slaves who were still living. This included a number of them who lived in Texas when they received word of the proclamation on June 19th, 1865. Since that was the day the last of the ex-slaves learned of the proclamation, June 19th was chosen to be celebrated as “Juneteenth.”

Emancipation had left an indelible mark on all of those former slaves interviewed by the Federal Writers’ Project.

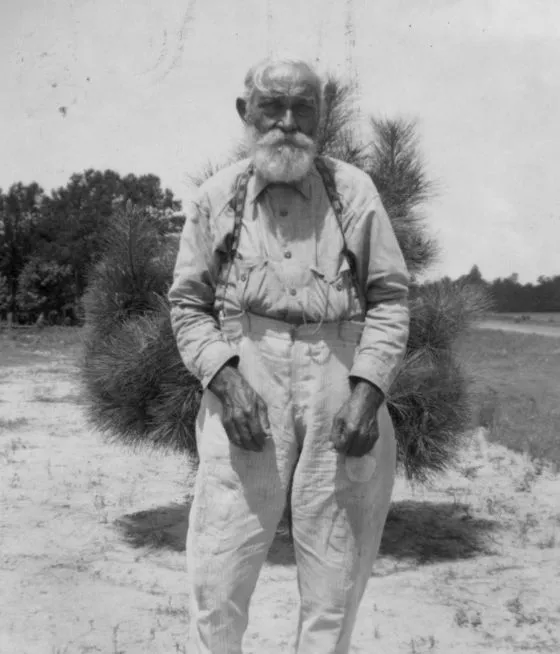

Preely Coleman

For example, Preely Coleman (left) was freed on June 19th, 1865, and shared his first experience of freedom when he was interviewed on June 19th, 1937.

He remembered his owner telling him and the other enslaved men working in the field that “you all are free as I am.” The men began “shouting and singing” in celebration.

Yet uncertainty remains

Although many African Americans certainly rejoiced that first Juneteenth, they also experienced the uncertainty of what freedom meant.

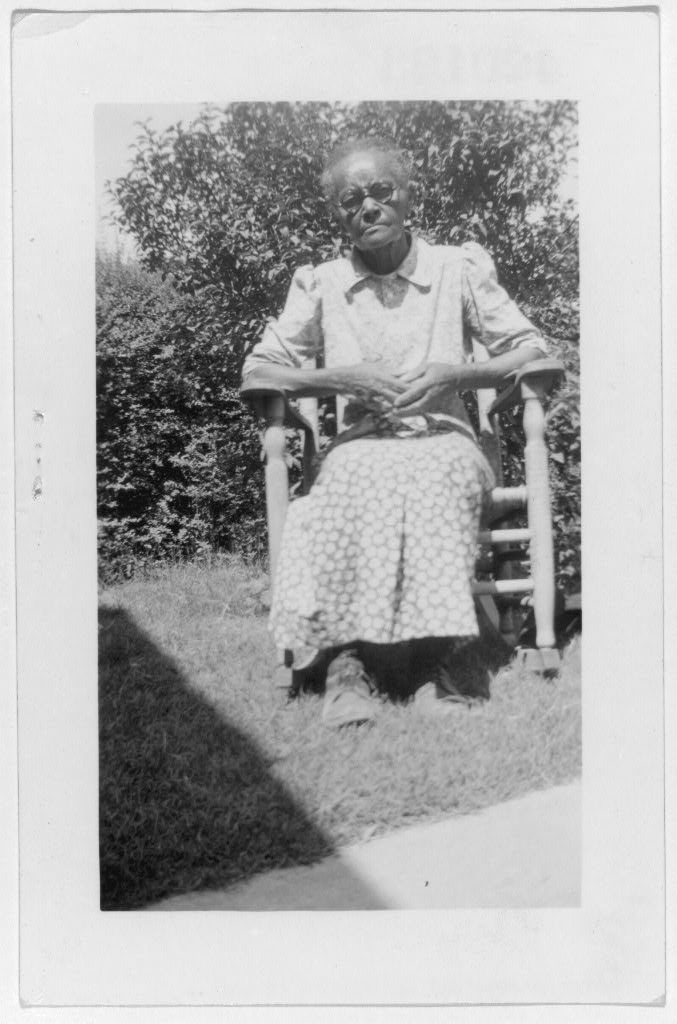

Margrett Nillin of Fort Worth lamented how freedom brought about an explosion of violence against African Americans, many of whom were shot, tortured, or lynched at the hands of former owners and the Ku Klux Klan.

In light of these awful attacks, the interviewer asked Nillin which she liked “best,” being free or being enslaved? Nillin replied that despite the uncertainty of freedom, under slavery she owned nothing and would “never” own anything, and could neither marry, nor buy a home, nor raise a family. But she felt that being emancipated gave her the freedom to own property, to marry and raise a family, to travel and work for wages, to worship and become educated.

Overcoming uncertainty through our Founding Principles

Our mission at the Jack Miller Center is to educate young Americans about the freedoms our country gives to us through our founding principles. Our country is not perfect, and never was perfect, yet we are getting closer and closer to realizing the vision from the Declaration of Independence, that “all men are created equal.”

Read the full Juneteenth story published at RealClear

Elliott Drago serves as the JMC’s Resident Historian and Editorial Manager. He is a historian of American history and the author of Street Diplomacy: The Politics of Slavery and Freedom in Philadelphia, 1820-1850 (Johns-Hopkins University Press, 2022).