I must have Kentucky

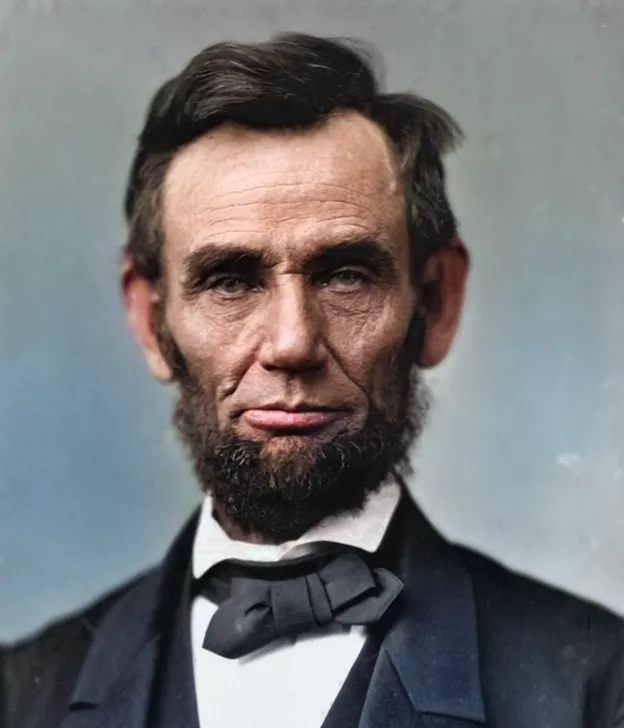

Many Americans associate Abraham Lincoln with the state of Illinois, but many Americans don’t realize Lincoln was born in Kentucky.

Born in Kentucky

After all, he launched his political career in Illinois, represented Illinois’ 7th district in the United States House of Representatives, won Illinois in the 1860 presidential campaign, and after his tragic death, was buried in Illinois.

But what many Americans don’t realize is that Lincoln was born in Kentucky and called it home for the first seven years of his life. The first president born west of the Appalachian Mountains, Lincoln resided in a humble log cabin first in Sinking Spring for two years and then in Knob Creek, Kentucky, which had some of the best farmland in the young state. While still more of a frontier than a settled space, Kentucky experienced a population boom throughout the 1810s, containing over 500,000 people by the time the Lincoln family decamped for Indiana in 1816.

Lincoln’s childhood years consisted of what he later described as, “The short and simple annals of the poor.” The young Lincoln detested toiling alongside his father on their farm, though the experiences imbued in him hard work, discipline, and an appreciation for the free yeoman farmers whose manual labor were foundational to the young nation. However, the presence of enslaved people throughout the South, including the 120,000 enslaved people in Kentucky in 1820, spoke to the inherent tensions of slavery within the United States. Lincoln would grapple with this tension throughout his life. His antislavery principles would later bring these laborers together, free and enslaved. Perhaps drawing on his memories of Kentucky decades later, Lincoln remarked, “each person is naturally entitled to do as he pleases with himself and the fruits of his labor.”

Did you know?

Despite his short residence in Kentucky, the state deeply influenced the course of Lincoln’s life: his wife Mary Todd was a native Kentuckian, as was his hero Henry Clay, a man who Lincoln eulogized and whose “deep devotion to the cause of human liberty” he hoped to emulate.

Kentucky also served as the site of a life-changing experience for Lincoln when he returned in 1841. While he and his best friend, Joshua Speed, traveled down the Ohio River on a steamboat, Lincoln came face to face with the brutality of American slavery: twelve Black Americans chained together, on their way to the Deep South for sale.

Writing to Speed’s sister Mary a short time later, Lincoln remarked how these men were

being separated forever from the scenes of their childhood, their friends, their fathers and mothers, and brothers and sisters, and many of them, from their wives and children, and going into perpetual slavery where the lash of the master is proverbially more ruthless and unrelenting than any other where…

Lincoln never forgot this image of the domestic slave trade on the Ohio River. In a letter to Joshua Speed in 1855, he wrote of the tensions of living in a half-free, half-slave United States, that at its foundation relied on the liberating pulse of the Declaration of Independence.

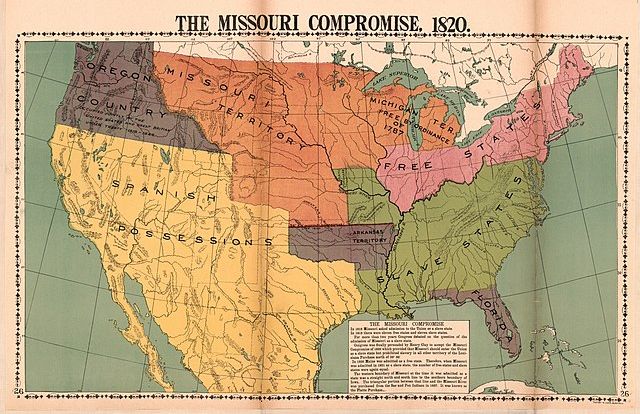

The political context of this letter laid bare the conflict over slavery would envelope the nation six short years later. Lincoln and Speed discussed the disastrous consequences of the Kansas-Nebraska Act. Under popular sovereignty, settlers were allowed to vote whether the new state would be free or slave. A mad rush of proslavery and anti-slavery zealots into Kansas territory erupted in bloodshed, and the proslavery forces voted in favor of the territory becoming a slave state. Just as important, this act repealed the Missouri Compromise.

Lincoln insisted that the Missouri Compromise, the brainchild of Henry Clay that determined free and slave states based upon the 36-30 geographic line, ought to be restored. That line limited the expansion of slavery, which Lincoln argued was in keeping with the Founder’s goal of letting slavery wither away and die. Repealing the Missouri Compromise violated what Lincoln later called “the leading principle” of the Declaration of Independence that all men are created equal.

Unlike Speed, a slaveowner himself who disliked slavery “in the abstract,” Lincoln was willing to place limits on slavery in a real, albeit cautious and pragmatic way. He expressed an authentic, righteous indignation when he chastised Speed about their shared memory of the enslaved men on the Ohio River:

In 1841 you and I had together a tedious low-water trip, on a Steam Boat from Louisville to St. Louis. You may remember, as I well do, that from Louisville to the mouth of the Ohio there were, on board, ten or a dozen slaves, shackled together with irons. That sight was a continual torment to me; and I see something like it every time I touch the Ohio, or any other slave-border…It is hardly fair for you to assume, that I have no interest in a thing which has, and continually exercises, the power of making me miserable.

Lincoln had an interest in freedom because he believed in the precepts of the Declaration of Independence. This sacred document held that “all men are created equal,” Lincoln wrote, not that “all men are created equal except negroes.”

Living with those immortal words of the Declaration, Lincoln argued that fundamental human equality meant an equal right to reap the fruits of one’s labor. Thus, even though he transformed from a lawyer to a congressman to the nation’s 16th president, his memories of hardscrabble farmers on the frontier and the toil of enslaved people on a riverboat remained deeply embedded in his moral psyche. In his words, “If slavery is not wrong, nothing is wrong.”

Lincoln’s short time in Kentucky exposed him to the dignity of honest toil and the brutality of slavery – yet he wove these experiences together in his understanding of the fundamental human equality enshrined in the nation’s founding principles.