Elon Musk and free speech

What James Madison and American history can teach us about current free speech questions in the age of social media

Is free speech really worth it?

Elon Musk’s first tweet after his $44 billion offer to purchase Twitter seemed uncontroversial enough,

“Free speech is the bedrock of a functioning democracy.”

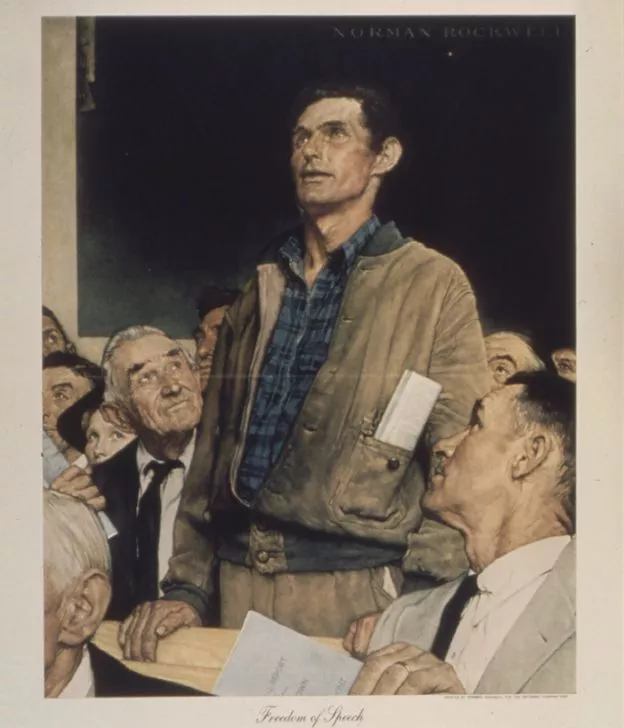

As the potential owner of the social media giant and self-proclaimed “free speech absolutist,” Musk promises to make Twitter the “digital town square where matters vital to the future of humanity are debated.”

But why are so many Americans divided on Musk’s pledge to provide an online space for free speech?

After all, the First Amendment declares that “Congress shall make no law … abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press”. While the First Amendment covers the government’s role in restricting speech, there have long been debates about how freedom of speech should be observed in the private sector.

In other words, the First Amendment doesn’t require Twitter to protect free speech—but should Twitter anyway?

In short, it’s complicated.

Enter the “Father of the Constitution”: James Madison

Madison presented his original proposal for the First Amendment on June 8, 1789.

Madison wrote,“The people shall not be deprived or abridged of their right to speak, to write, or to publish their sentiments; and the freedom of the press, as one of the great bulwarks of liberty, shall be inviolable.”

Although refined by the time of its inclusion in the Bill of Rights, the spirit of Madison’s words remained intact: freedom of speech was a prerequisite to self-government.

Writing later in 1791, Madison asserted, “Public opinion sets bounds to every government, and is the real sovereign in every free one.” In other words, governments that place boundaries on free speech create societies in which the people can never truly rule.

One of the first big tests came when the Adams administration introduced the Alien and Sedition Acts in 1798.

Anticipating a war against France, Adams and the Federalists “feared that ‘aliens’, or non-citizens, living in the United States would sympathize with the French during a war.” The collection of laws imposed strict limits on speech that was critical of the American government and authorized the president to deport or imprison “aliens”.

Madison and Thomas Jefferson asserted that such actions undermined a free republic. Both men went so far as to argue that states could interpose (i.e., insert themselves between) or even nullify abuses by the federal government.

Simply put, Madison believed that the First Amendment gave Americans free speech as well as the voice of self-government, even if a minority of them misused free speech.

What might Madison think about Elon Musk, Twitter, and free speech “absolutism”?

And why does it matter in the modern world?

According to Madison expert and JMC fellow Colleen Sheehan, Madison argued that free speech encourages a “commerce of ideas” that allows a society to refine their arguments and “make a ‘common cause’ together, despite the many ways we are different and diverse.”

We cannot speak for Madison. But efforts that remind us of the important role free speech—and our Constitution more broadly—plays in our individual lives help preserve our free society, a central goal of all the founders in establishing a self-ruling form of government.

At the Jack Miller Center, we believe that understanding our nation’s history and founding principles are the best way to make progress on these important questions. Freedom of speech is no exception. Students and teachers alike will benefit from our aggressive programming in civics education that promotes these principles in a faithful and responsible way.

Want to help the Jack Miller Center transform higher education?

Donate todayRelevant readings from JMC fellows & faculty partners

Jeremy Bailey, James Madison and Constitutional Imperfection. (Cambridge University Press, 2015)

Jeremy Bailey, “Should We Venerate That Which We Cannot Love?: James Madison on Constitutional Imperfection.” (Political Research Quarterly 65.4, December 2012)

Jeremy Bailey, “Was James Madison ever for the bill of rights?“ (Perspectives on Political Science 41.2, 2012)

Colleen Sheehan, “Deliberative Republicanism, Political Communication, & the Sovereignty of Public Opinion.” (A Madisonian Constitution for All, National Constitution Center)

George Thomas, The Madisonian Constitution. (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2008)

George Thomas, “The Madisonian Constitution, Political Dysfunction, and Political Polarization.” (Parchment Barriers: Political Polarization and the Limits of Constitutional Order, University Press of Kansas, 2018)

George Thomas, “Recovering the Political Constitution: The Madisonian Vision.” (The Review of Politics 66.2, Spring 2004)

Gregory Weiner, “‘The Ultimate Justice of the People’ Madison, Public Opinion and the Internet Age.” (A Madisonian Constitution for All, National Constitution Center)