“A bully speech”

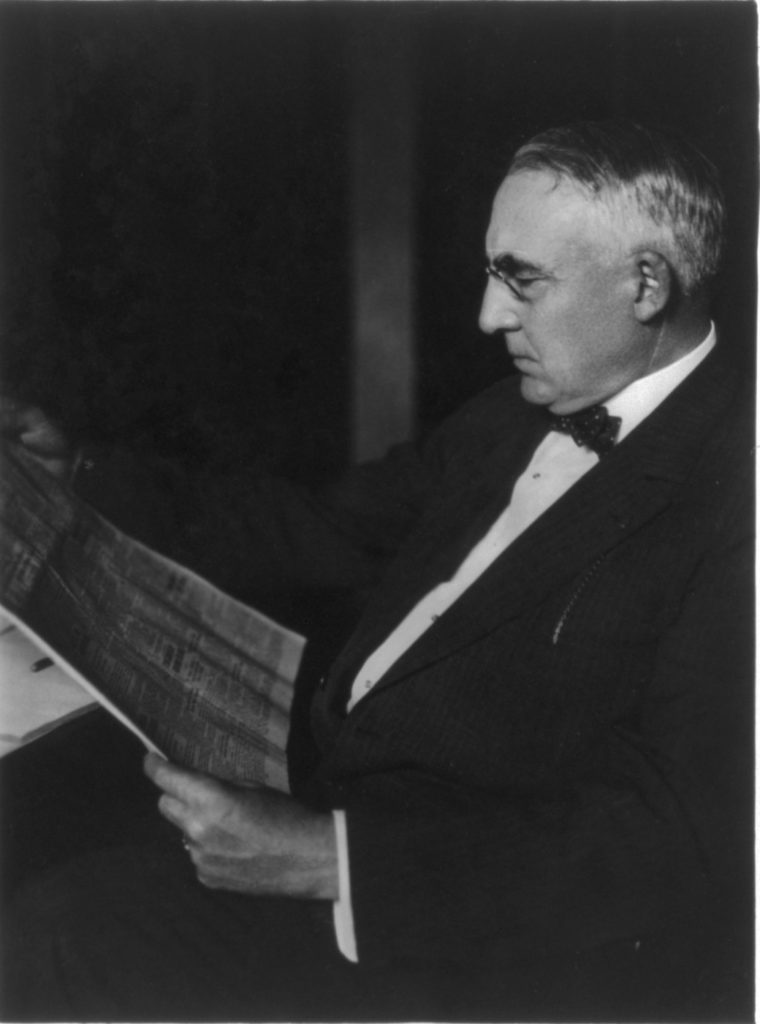

Many Americans have forgotten about President Warren G. Harding; however, this story highlights some memorable words from President Harding.

A man of limited talents

If they remember him at all, it’s usually for the scandals that rocked his administration or possibly his premature death while in office.

Lest we continue to forget him, we ought to spotlight two significant speeches he delivered shortly after taking office in 1921.

The first speech took place at Lincoln University in Pennsylvania; the second at Birmingham, Alabama’s semicentennial celebration. These two moments from his short term in office make Harding unforgettable and perhaps shed light on how to promote healthy race relations in our nation today.

Lincoln University, esteemed as both the “Black Princeton” as well as the country’s first degree-granting Black university, invited Harding as its commencement speaker for spring 1921 – Harding accepted. His speech was poignant, as the graduation took place a mere three days after the Tulsa massacre. There, hundreds of Black Americans lost their lives at the hands of vengeful whites, after a Black man named Dick Rowland was accused of assaulting a white woman in an elevator. Over the course of the next 24-hours, marauding whites wreaked havoc throughout the predominantly Black Greenwood neighborhood, incinerating over 35 square blocks of Black-owned businesses, including the city’s “Black Wall Street,” and dozens of homes. The Tulsa massacre shocked the nation – and Harding responded in a way no president had before him.

As a Republican, Harding took his role seriously as a President representing the party of Lincoln and the party overwhelmingly supported by Black Americans. Not only did he take the unprecedented step of speaking at a Black university, he went even further and commented on both race relations and the tragedy at Tulsa.

Harding addressed the 400 graduates as his “fellow countrymen,” noting how Black American’s contributions during the Great War (i.e., World War I) “earned the right to be memorialized.” Thus, in addition to delivering the commencement address, Harding also went to the university to help dedicate a Memorial Arch honoring Blacks who fought in that war. He focused on connecting their wartime efforts to the educational work performed by Lincoln University, stating that although “no Government can wave a magical wand and take a race from bondage to citizenship in half a century,” government could produce opportunities for a “good citizenship.”

Key to overcoming the imposed limitations of American society was “educational preparation” like that afforded by Lincoln University. He closed by juxtaposing Black American citizenship and education with the “unhappy and distressing spectacle” of Tulsa. While Harding’s speech lasted barely ten-minutes, what he did next would have astonished most Americans of the time: he personally congratulated and shook the hands of each Black American who graduated that day.

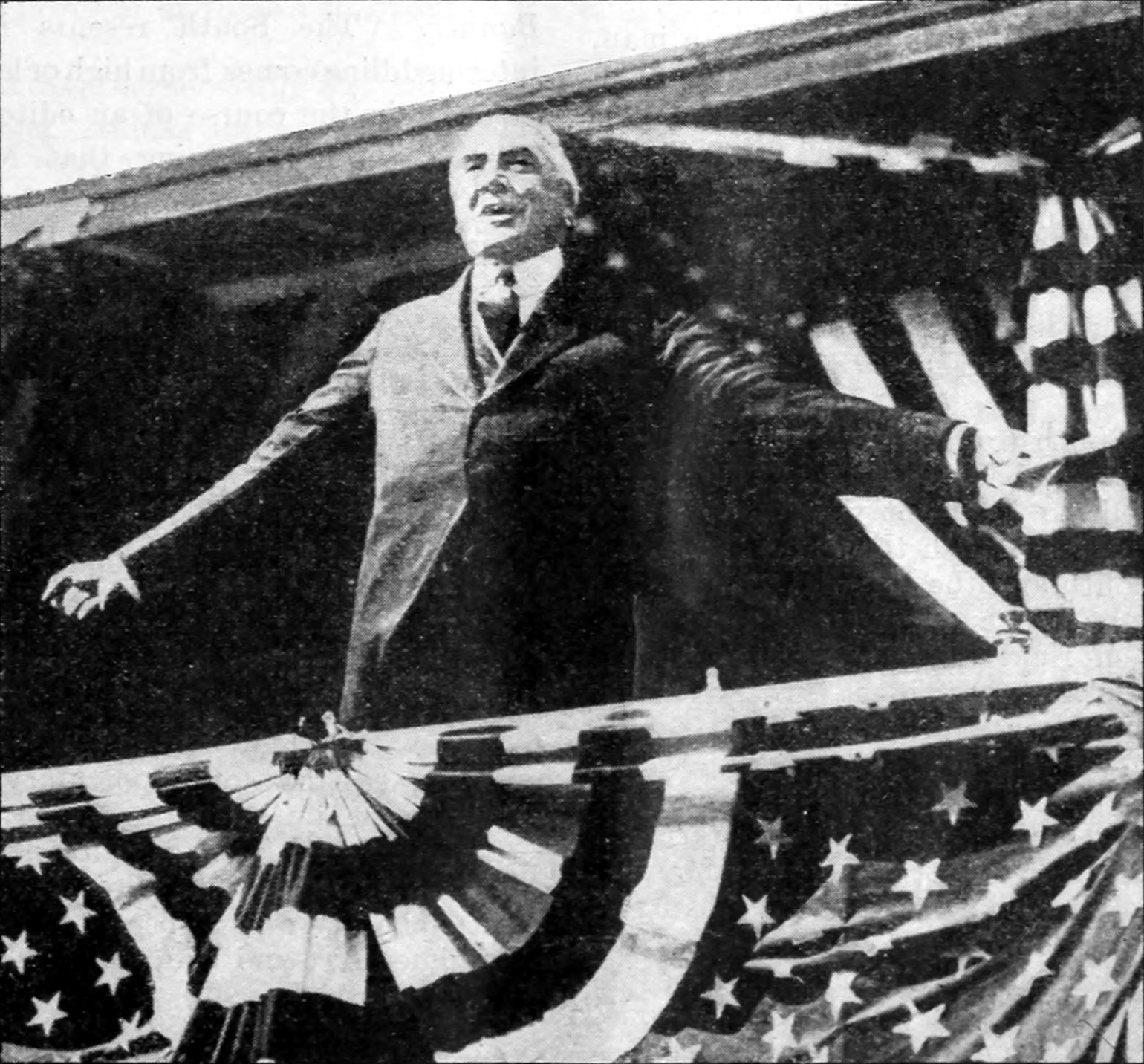

That fall Harding became the first sitting president to go into the Deep South since the Civil War. At Birmingham, he spoke before a crowd of 30,000+ Alabamians, a third of whom were Black Americans. According to The Montgomery Times, a serpentine wire fence “streaked and zigzagged” its way through the audience, separating them by skin color – a stark reminder of Southern segregation at its apex.

Harding’s speech began simply enough. He praised the “magic city” and “wonder” of Birmingham as a shining symbol of the steadfast and prosperous growth of Southern industry in the years following the Civil War. He skirted the issue of slavery in the war, preferring instead to reconcile sectionalism through the robust nature of the modern American economy, which he called “the most characteristic and most revolutionary development of the struggle.”

If the speech ended there, with Harding playing safely by expressing gratitude and humility toward the South, maybe the speech would truly be forgotten by Americans then and now.

But the speech did not end there. His commending of Southern industry quickly transformed into an ambitious call for the political, economic, and educational equality of Black Americans. The Great War became an opportunity for Blacks to recognize their “first real conception of citizenship,” one that Harding argued ought to extend to the political act of voting. The “possibility of economic equality” based on the individual capacities and efforts of the Blacks themselves would further bolster Southern industry and be a boon to the national economy. Dumbstruck, whites in the audience stood with mouths agape as Harding boldly stated “let the black man vote when he is fit to vote; and prohibit the white man voting when he is unfit to vote.” Harding continued, proposing that Southerners needed to afford Black Americans equal educational opportunities, enabling them to “develop their own leaders” and participate “in the universal effort for the advancement of humanity as a whole.”

According to The Cullman (AL) News of October 20th, these remarks met with “stony silence” from the whites in the audience. At this point, a visibly angry Harding departed from his speech and in a stern voice told the crowd,

What I say on this I say to all America, north and south, white and black. Whether you like it or not, unless our democracy is a lie, you must recognize that equality.

Again, “absolute silence” from the white audience. The Black members of the audience reacted quite differently, exploding with “uproarious applause” at Harding’s words, according to The Montgomery Times.

Before we turn Harding, the self-described “man of limited talents,” into a visionary, we must remember that he qualified his views on race. As the historian Katherine Sibley wrote, “the speech did not call for social equality (indeed, he argued against it) and in the end did little to change the oppressive conditions in which many blacks lived in the 1920s.” Nevertheless, Harding’s “open and approachable manner” toward Black Americans spoke to the gumption he possessed when discussing race relations: after all, no other president before him had delivered a speech in the Deep South that confronted white southerners with the plain fact that Blacks deserved some forms of equality.

Harding confidante Malcolm Jennings wrote the President shortly after his trip to Alabama, calling his words there a “bully speech,” and adding that “if it had to be made, it was of course best that it be made in the South.”

The Southern press responded to the speech with sharp disdain. According to The Birmingham News, white Southerners displayed a palatable “lack of enthusiasm” for the speech, denouncing as intolerable what they viewed was Harding’s true objective: forcing social equality on the South and the “eradication” of the color line.

The Black-run Birmingham newspaper The Voice of the People argued that although Harding was a friend to Black Americans, white Americans needed to adopt a more proactive approach:

…the best possible white friend to the colored man today is that white man who goes in and out, passing to and fro with words of cheer and comfort, and who will go every inch of his cable toe for his colored neighbor.

Indeed, W.E.B. Du Bois complimented Harding for promoting economic, educational, and political equality, but lamented a “grave crisis” if social and racial equality could not be achieved. Yet still other Black leaders like Marcus Garvey (middle) praised Harding’s speech, and Dr. Robert R. Moton (bottom), principal of the Tuskegee Institute, even called it “the most important utterance on the question by a President since Lincoln.”

Making sense of Harding’s speech in terms of his time and the progress we have made since 1921 requires one final juxtaposition of reactions.

Major Adam E. Patterson wrote in the Voice of the People that he ranked Harding’s speech in Birmingham as on par with Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address. Patterson, who served with distinction as the first Black Judge Advocate of the all-Black 92nd Division in the Great War, felt grateful for the President’s words, “especially so since he made it where it will do the most good.” Georgia Senator Thomas Watson was not a fan of Harding’s speech. Watson lamented how Harding’s words on equality planted “fatal germs in the minds of the black race.” Like many white Southerners, Watson believed that theoretical whiffs of political, economic, or educational equality with Black Americans would metastasize into unacceptable social and racial equality, and his reasoning featured in The Selma Times-Journal is worth quoting at length:

If the President’s theory is carried to its ultimate conclusion, namely, the that black person either man or woman, should have full economic and political rights with the white man and white woman, then that means that the black can strive to become President of the United States; hold cabinet positions, and occupy the highest places of public trust in the nation…I am against any such theory because I know it is impracticable, it is unjust, and it is destructive of the best ideals of America.

We may have forgotten about Harding’s presidency, his public display of support for Black Americans at Lincoln University, and his controversial speech in Birmingham. Yet we do remember the ideal of equality rooted in America’s founding principles, the same ideals that Harding espoused as best he could in 1921, and the same ideals that Americans like Major Patterson embraced and Senator Watson saw as being threatened when faced with their just and visionary realization. Harding did not advance race relations by today’s standards, but in his Birmingham speech we find a striving to further cement equality for all Americans.

In the century since Harding delivered his “bully speech,” Americans have achieved significant victories that few in 1921 could imagine, from desegregated public education to strengthened voting legislation to Black Americans assuming the highest offices in the nation.

Warren G. Harding was no visionary, but his willingness to address equality, however qualified, in an unequal society makes him an unforgettable president.

This post was also featured on RealClear History.

Elliott Drago serves as the JMC’s Editorial Officer. He is a historian of American history and the author of Street Diplomacy: The Politics of Slavery and Freedom in Philadelphia, 1820-1850 (Johns-Hopkins University Press, 2022).