Educating Sgt. York

The story of Sgt. Alvin York, a real American hero on and off the battlefield.

“A tolerable few”

Alvin’s eyes scanned the valley.

Everywhere he looked, young men fell “like the long grass before the mowing machine.”

Where’s the artillery? he wondered.

Nearby a panicked sergeant commanded his men to outflank the machine gunners perched in the surrounding hills. They could maybe, just maybe, dislodge the Germans and take the rail station. At the very least, they needed to get out of the valley. Now.

As if on cue, the American artillery rained hellfire down upon the valley, creating havoc among both American and German soldiers.

Sergeant Alvin C. York and 16 other soldiers sprang into action.

The smoke and brush obscured them as they flitted up and over the hill. What greeted them on the other side seemed absurd: 70 German soldiers eating their breakfast – “a mess of beef-steaks, jellies, jams, and loaf bread all around,” amidst the morning fog.

Born in the hills of Fentress County, Tennessee in 1887, Alvin C. York’s early life resembled that of other legendary American frontiersmen. Like Daniel Boone and Davy Crockett, he lived in a log cabin, endured an impoverished upbringing, possessed little formal schooling, and spent countless hours exploring and hunting in the forest and hills around his family’s home.

A gambling, hard-drinking pugilist as a young man, the death of his best friend in a bar fight served as a wake-up call. York gave up the life of a drunken, fist-fighting wastrel and converted to Christianity, becoming a pacifist as well as one his local church’s elders, even leading the choir with his mellifluous voice.

A pacifist who was a deadly shot

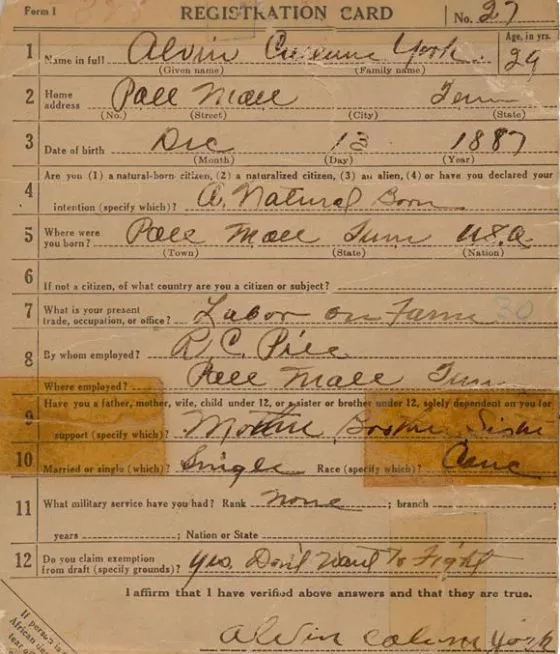

York’s conversion and pacifism occurred just as war broke out in Europe and a subsequent draft was instated in the United States. York received his draft card in June 1917. Next to the question “Do you claim exemption from draft (specify grounds)?” he wrote “Yes, don’t want to fight.”

The Army ignored York’s words and instructed him to report for basic training at Camp Gordon, Georgia. There, he became a walking-talking paradox to his fellow soldiers: despite his fondness for quoting Bible verses and stubborn pacifism, he was the deadliest marksman in camp, drawing from years of experience hunting and shooting in Tennessee.

Living this paradox eventually brought York to a breaking point, prompting a long debate with his commanding officer over Christianity and war’s fundamental dictum: kill or be killed. Luckily for York, his commanding officer granted him a short leave to meditate on these thoughts and feelings. York retreated to Tennessee, wandering for days through his childhood forests, and experienced an epiphany: God wanted him to fight for his country to help rid the world of evil.

Along with the rest of the men in Company G of the 328th Infantry Regiment, Corporal York was sent to the hellish front lines of Western Europe. Mired in the bloody muck of trench warfare for four years, at times advancing barely a few hundred yards with each charge across no-man’s-land, Allied forces in Europe welcomed the arrival of American troops in June 1917.

The Americans had fought in Europe for roughly a year by the time York and his company arrived, and it was clear the Allies now carried the necessary momentum to launch a great offensive: the 1918 Meuse-Argonne campaign, in which the Allies planned to attack the heavily-defended Germans positioned in the almost impenetrable Argonne forest, push them all the way back to the Meuse River to cut off a crucial German railroad junction , and potentially collapse the entire German front.

For perspective, the Allied forces sought to take territory in a matter of weeks that they could not conquer in the previous four years.

Here on the front lines of the Meuse-Argonne campaign was the crack-shot pacifist, Alvin C. York. He and 16 other soldiers, a hodgepodge of survivors from the firefight in the valley, had stumbled upon the breakfasting Germans, all of whom were unarmed, save for their Leutnant (German for “Lieutenant”). Knowing they were outnumbered at least 4 to 1 and behind enemy lines, the Americans screamed “put them up” at the enemy soldiers. The Germans obeyed, as many believed the 17 Americans in front of them were merely the tip of an Allied offensive.

The two sides stared blankly at each other until a few German machine gunners from a nearby hill opened fire on the Americans, killing six and wounding three. With the Americans distracted, the German Leutnant seized the opportunity and blew his whistle: all the unarmed Germans hit the ground, leaving the bewildered Americans standing alone. The Leutnant yelled to the other German machine gunners on the hill who cut down all but three of the Americans.

“I was right out there in the open,” York later wrote. True to form, he stood his ground and aimed his rifle at the machine gunners,

jes like we often shoot at the targets in the shooting matches in the mountains of Tennessee; and it was jes about the same distance. But the targets here were bigger. I jes couldn’t miss a German’s head or body at that distance. And I didn’t. Besides, it weren’t no time to miss nohow…every time a head come up I done knocked it down.

York killed at least 20 of the 30 German machine gunners in that fashion, and then shot and killed six more German soldiers who made the mistake of charging him. The German Leutnant could not believe his eyes; speaking to York in English, he pleaded “If you won’t shoot any more I will make them give up!” He blew his whistle again, prompting the remaining gunners to disarm and gather in front of York, who now found himself in charge of over 100 enemy prisoners.

He did not bask in any military gusto or martial bravado. Instead, York felt a deep sense of responsibility and magnanimity toward the prisoners. They came under heavy German and American shelling as they approached the American lines, prompting York to order the Germans to run as fast as they could. He later explained how, “There was nothing to be gained by having any more of them wounded or killed. They done surrendered to me and it was up to me to look after them.” Due to York’s efforts, he safely led 132 German prisoners to American lines. A dumbfounded lieutenant met him outside of the American command post and asked, “York, have you captured the whole German Army?”

“I have a tolerable few,” York replied.

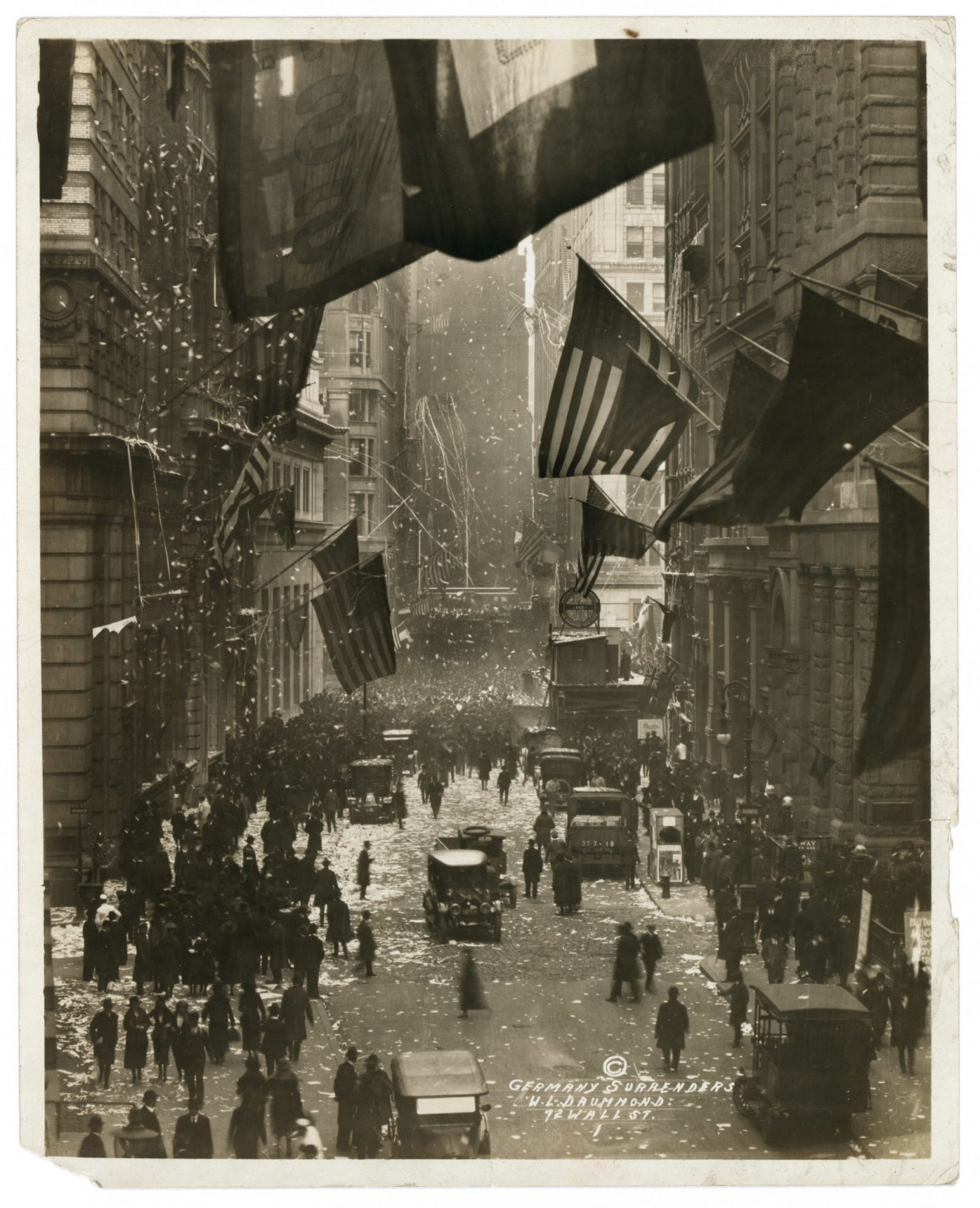

One might expect a war hero to revel in their newfound celebrity upon their return to the United States, to city streets festooned with patriotic decor and broad metropolitan avenues alive with ticker-tape parades.

York certainly felt honored by these festivities; he was humbled further when Supreme Allied Commander Marshal Ferdinand awarded him the French Croix de Guerre, calling York’s exploits “the greatest thing accomplished by any private soldier of all the armies of Europe.”

Even after receiving the Congressional Medal of Honor, York remained circumspect about his surging popularity. Always more comfortable surrounded by the bucolic Tennessee hills, he returned to his native state, married his childhood sweetheart, and turned down lucrative offers from vaudeville promoters, stage producers, and film directors. He refused to exploit his fame for personal gain.

However, York’s experiences in the first World War did change him. He saw the violence and folly of modern industrial warfare firsthand and longed to harness the positive aspects of an increasingly mechanized world. His time at war inspired his life mission: raising money to promote educational opportunities for the children of Tennessee.

In 1926, York wrote, “When I went out into that big outside world I realized how uneducated I was and what a terrible handicap it was. I was called to lead my people toward a sensible modern education.”

Three years later he founded the Alvin C. York institute near his childhood home in Tennessee. This private school provided free education for the children of Fentress County, many of whom languished in poverty, and emphasized the teaching of agricultural and industrial arts. Unfortunately, the precarities of the Great Depression disrupted the school’s funding, forcing York to mortgage his farm and take loans to keep the school operating. By 1937 the dire straits of the school’s finances led to its takeover by the state of Tennessee and the undeserved demotion of York as school administrator.

Regardless of the state’s takeover of the school, York put his dreams into practice: he never stopped fundraising to educate the youth of his state and region. His deep sense of responsibility toward helping those close to him and those who needed the most help cemented his magnanimous legacy, from American and German soldiers to children from the Tennessee hills.

Decades after the war, York was asked by a reporter, “how do you want to be remembered?” Rather than focus on his wartime heroics, he gave his characteristic modest answer: “For improving education in Tennessee.”

Elliott Drago serves as the JMC’s Editorial Officer. He is a historian of American history and the author of Street Diplomacy: The Politics of Slavery and Freedom in Philadelphia, 1820-1850 (Johns-Hopkins University Press, 2022).