A significant office

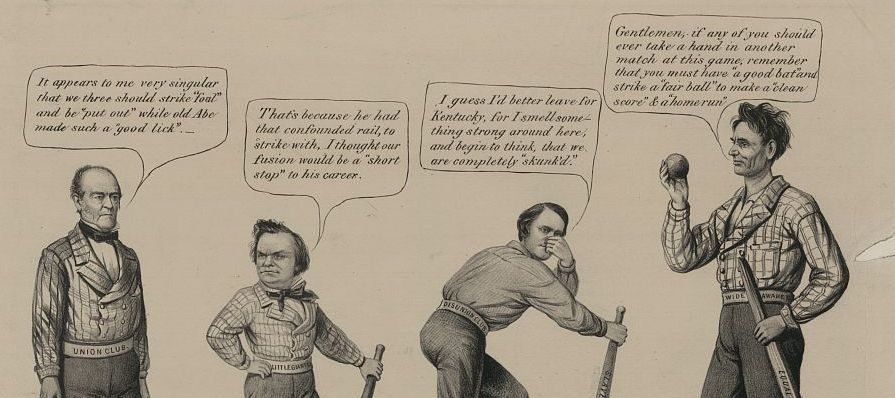

Each presidential election cycle brings out a hurly-burly cast of characters. “A significant office” spotlights the running mates from the 1860 presidential election.

The Second Officer of the Government

Some of these figures become immortalized through victory, others, lost in the historical fog of defeat. Let us take a moment to study a few of the fascinating characters from the most consequential presidential election in American history: the election of 1860.

So, what do we already know about that election? Most Americans know how the election of Lincoln led to the secession of the slave south and ushered in four years of bloody civil war. And many Americans may remember how the Democratic Party split in 1860, which helped catapult Lincoln to the presidency – despite only receiving 39% of the popular vote.

Fewer Americans can name all four presidential candidates or perhaps even explain the platform of the Constitutional Union Party (spoiler alert: they supported the Constitution and the Union without a firm stance on the hot button issue of slavery).

Yet everyone knows that presidential candidates require running mates for what John Adams once called, “the most insignificant office that ever the Invention of man contrived or his Imagination conceived”: the Vice Presidency. While obscure to us today, these figures possessed enough political renown in their own time to be considered viable candidates for this position.

Who were these men who could have held such a sway during the worst war our country has ever seen?

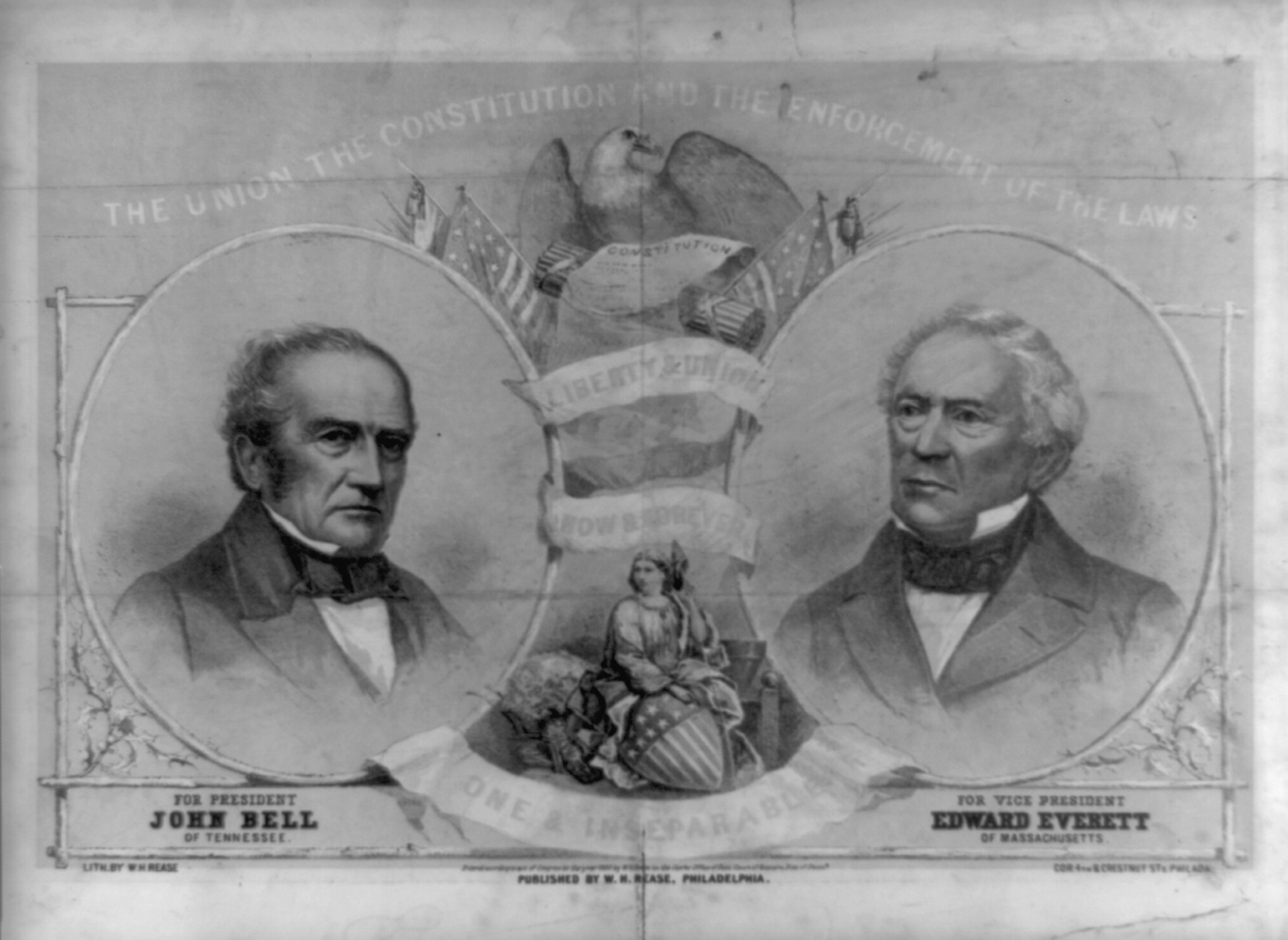

The Constitutional Union Party

Led by presidential candidate and former Speaker of the House John Bell, the Constitutional Union Party sought to avoid secession at all costs by recognizing “no political principle other than the Constitution of the country, the Union of the states, and the Enforcement of the Laws.” A hodgepodge of disaffected Whigs and Know Nothings, their platform garnered support from the Upper South states of Tennessee, Kentucky, and Virginia, receiving 39 electoral votes in 1860. The Constitutional Union Party ultimately failed because appeared two-faced on the slavery issue by promising to protect it in one section and “denying that support in the other.”

To balance Tennessean John Bell’s status as a slaveholder, the party selected the former Whig governor of Massachusetts, president of Harvard, and acclaimed orator Edward Everett as the vice presidential candidate. Despite his fame as a stirring and impassioned speaker who attracted thousands of spectators, Everett and his party’s vague and noncommittal responses to the slavery question fell flat across the Deep South. Further disrupting the party’s chances, late in the campaign southerners became fixated on Everett’s refusal to retract his view on slavery as a “social, political, and moral evil.”

Concerned with unity, Everett essentially blamed Lincoln’s election for secession and the dissolution of the Union. Ironically, he would share the spotlight with Lincoln at a small Pennsylvania town in November 1863. There, Everett roused a crowd of 20,000, many of whom came to see him, the most famous American orator since Daniel Webster, deliver a two-hour behemoth speech describing the entire course of the Civil War. In his conclusion, he assured the audience that the war would soon end, as “The people of the South are not going to wage an eternal war for the wretched pretexts by which this rebellion is sought to be justified.”

Lincoln spoke so briefly that a contemporary photograph barely catches him sitting down – and yet his Gettysburg Address would be remembered forever. Everett praised Lincoln for conveying in two-minutes “the central idea of the occasion” – rechristening the Union with the promises of the Declaration of Independence. He soon befriended Lincoln and worked earnestly on the latter’s 1864 reelection campaign before dying in early 1865.

Lincoln spoke so briefly that a contemporary photograph barely caught him sitting down – and yet his Gettysburg Address would be remembered forever. Everett praised Lincoln for conveying in two-minutes “the central idea of the occasion” – rechristening the Union with the promises of the Declaration of Independence. He soon befriended Lincoln and worked earnestly on the latter’s 1864 reelection campaign before dying in early 1865.

The Southern Democrats

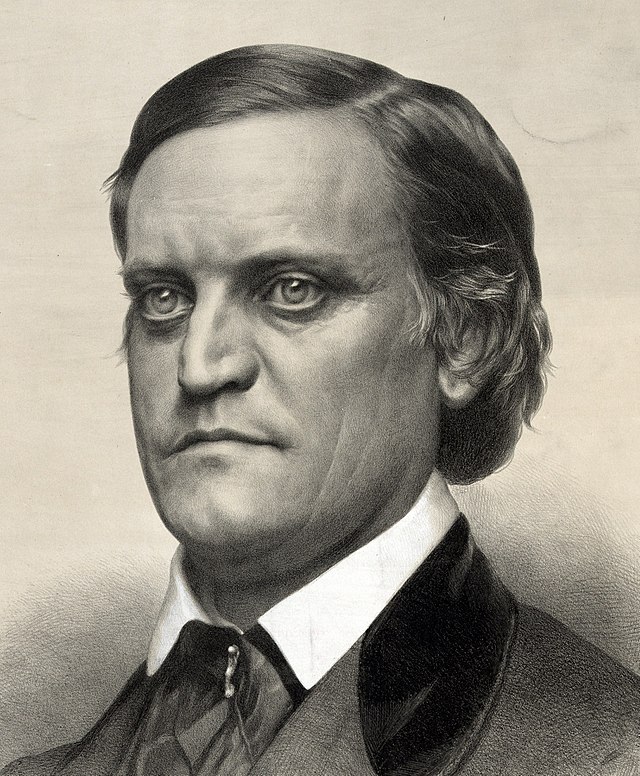

As mentioned, the Democratic Party split in 1860 over the issue of slavery. The Southern Democrats, led by then-Vice President and slaveholder John Breckinridge, demanded the unfettered expansion of slavery into the territories and that northern states honor the Fugitive Slave Act. Breckinridge also supported the south in seceding if slavery did not receive additional constitutional protections. The Southern Democrats captured most of the slave states, including all the Deep South States, winning the second-most electoral votes in the 1860 election.

Oregon’s first governor and one of its first senators Democrat Joseph Lane accompanied Breckinridge on the Southern Democratic ticket. A North Carolinian by birth, Lane became a hero during the Mexican-American War and by the 1850s firmly established himself as the Democratic Party boss in the Oregon Territory. His experiences out west led him to become a fierce proponent of states’ rights doctrine, especially regarding Black emigration into Oregon.

Lane dwelled on this topic for the majority of his first Senate debate, stating that he supported the new state’s constitutional prohibition on Blacks entering the state. “We do not want him there,” Lane explained, nor did he want them to achieve “all other rights that white men enjoy.”

However, the Oregon constitution also prohibited slavery, and as a result, Lane’s strident proslavery views contradicted the views of antislavery Oregonians in the Republican Party. Lane’s defense of southern secession in early 1861 further alienated him from Republicans in his home state, leading to his ousting as a senator; his son, John Lane, also left West Point at that time to accept a commission in the Confederate Army and fought in 23 battles before the war’s end. The elder Lane retired from politics in 1861 and moved back to Oregon, where he died in 1881.

The Northern Democrats

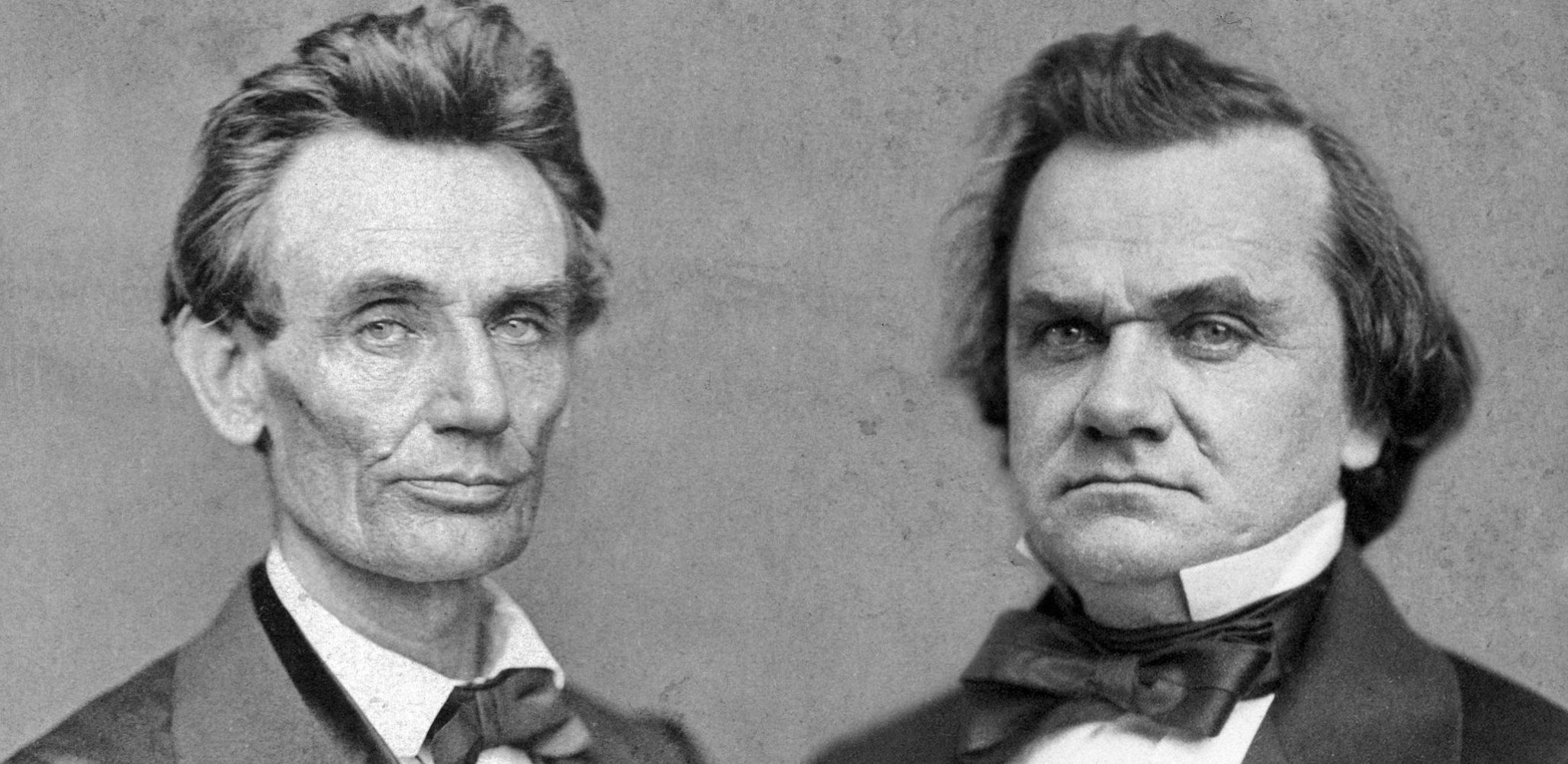

Perhaps the best-known politician of the day took the helm of the Northern Democrats. Illinoisan Stephen Douglas towered over his peers, having spent most of his political career hammering out legislation regarding slavery’s expansion in hopes of keeping the country together. Fashioning himself a preeminent compromiser on par with Daniel Webster and Henry Clay, Douglas’ politicking brought about the passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Act. The act allowed settlers of a territory to vote whether to allow or prohibit slavery. This act repealed the Missouri Compromise of 1820, which limited the territories open to slavery.

The Republican Party originated in opposition to the Kansas-Nebraska Act and the expansion of slavery, and Douglas seemed the greatest threat to that party’s chances for victory in 1860.

A highly controversial and fraud-ridden state constitutional convention in Lecompton, Kansas resulted in a proslavery constitution and quickly drew the ire of Douglas, who viewed the document as an illegitimate exercise in popular sovereignty. His undying loyalty to popular sovereignty did not reassure Deep South Democrats who desired to expand slavery. The Democratic Party held two conventions (one in Charleston and one in Baltimore) in 1860, both of which failed to rally around Douglas as their candidate; many southern Democrats boycotted the second convention while others simply walked out in protest.

When it came time to nominate Douglas’ running mate, the convention selected Herschel Vespasian Johnson, a former governor and senator from Georgia, to try and recoup southern support. Johnson’s staunch unionism combined with his southern roots and status as a slaveholder seemed like surefire assets to propel Douglas to the presidency. When Georgianshad convened to debate the Compromise of 1850 ten years prior, Johnson pledged in the convention manifesto to “resist” congressional interference in southern slavery, arguing that secession should be a “last resort.” Thus, by all appearances the Douglas-Johnson ticket “stood for conservatism and made for the preservation of the Union.”

Ironically, even though the Northern Democrats received the second-most popular votes, they received a paltry 12 electoral votes in the election of 1860.

Writing in a public letter a week after the election, Johnson explained that the fateful “error” of the Democratic Party’s schism made Lincoln’s presidency inevitable. He cautioned those allured by secession, urging his fellow Georgians to remain steadfast in their loyalty to the Union. After all, he argued, the federal government consisted of three branches of government:

The President is powerless, without the concurrence of both houses of Congress. But both are known to be opposed to the federal principles and policy of the Republican party. How is it possible then for Lincoln to commit any aggression upon the South? He cannot organize his administration except by the approval of the Senate; no measure can be adopted, without the action of Congress. He can do nothing of himself. He is at the mercy of Congress – subject really to its dictation – as powerless as Sampson shorn of his locks. Therefore, when it is asked, will you submit to the rule of Lincoln? I reply no; I am not under his rule, but under the rule of the government whose legislative department is known to be friendly to the constitutional rights of the South. He is the one who is under rule-bound hand and foot.

Despite his “bitter opposition” to secession, Johnson and his pro-union colleagues, including the future vice president of the Confederacy Alexander Stephens, failed when faced with colleagues like North Georgia’s Joseph E. Brown, who stoked popular fears that failing to back the enslaver’s revolt would doom white Southerners.

Johnson reluctantly followed Georgia into secession, becoming a senator in the Second Confederate Congress, albeit one who in time opposed wartime policies like conscription and the suspension of habeas corpus. Confined to prison after the Confederacy collapsed, Johnson was released by President Andrew Johnson after the personal intervention of Adèle Cutts Douglas, the widow of his former running mate, Stephen A. Douglas. Johnson later served as president of Georgia’s constitutional convention in 1865 and was chosen to serve as the state’s senator in 1866, though was refused this position due to the Fourteenth Amendment’s prohibition on former Confederates holding office. The Amnesty Act of 1872 removed this prohibition, and Johnson was soon elected judge of the middle circuity of Georgia 1873, a position he held until his death in 1881.

The Republican Party

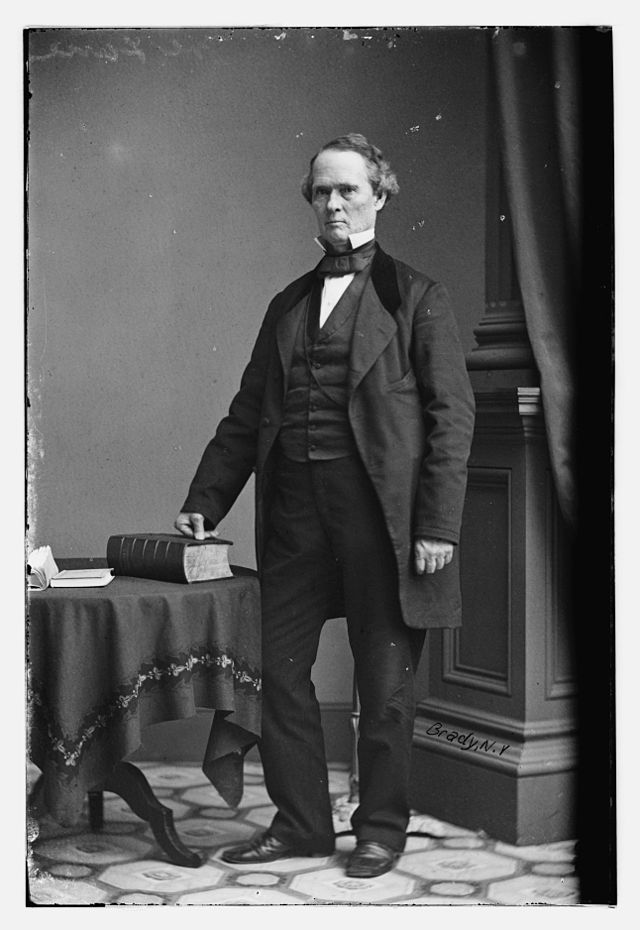

The Republican Party’s platform in 1860 decried the expansion of slavery as a “dangerous political heresy” that represented an affront to the founders’ vision enshrined in the Declaration of Independence. With Abraham Lincoln as its presidential candidate, the Republicans needed a vice presidential candidate who could garner support from New England and former Democrats. Senator Hannibal Hamlin of Maine fit the bill and became the perfect counterbalance to Illinois’ former Whig congressman Lincoln.

Hamlin had built his political career upon his “fidelity to political friends,” i.e., networking ability, as well as his principles. Having first served as a Democrat in both the state and national legislature in the 1830s and 1840s, Senator Hamlin became an outspoken critic of the Democratic Party’s support of slavery after the passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Act. In 1856, the Republicans promised Hamlin another term as senator if he agreed to leave the Democratic Party and run for Governor of Maine. Hamlin agreed and delivered a fiery farewell speech to the Senate on June 12, 1856, in which he proclaimed his principles and ferociously attacked his former party:

I hold that the repeal of the Missouri compromise was a gross moral and political wrong, unequaled in the annals of the legislation of this country, and hardly equaled in the annals of any other free country…from which so many evils have already flowed – from which, I fear, more and worse evils must yet be anticipated.

Hamlin was of course correct in his prediction, as seven slave states seceded after the election of Lincoln in 1860; four more states would secede following the attack on Fort Sumter. And like first Vice President John Adams, Hamlin found himself hemmed-in by this position, stating “There is a popular impression that the Vice President is in reality the second officer of the government not only in rank but also in power and influence. This is a mistake.” On the other hand, Hamlin wielded at least some power and influence, as his encouragement of Lincoln to issue an immediate emancipation proclamation and arm Black troops later bore fruit when the president met and shared a draft of the Emancipation Proclamation with Hamlin before anyone else in his cabinet. Furthermore, despite his lack of enthusiasm for the vice presidency, he did cultivate a friendship of “entire harmony and intimate and unreserved cordiality” with Lincoln.

Years later, in the 1864 presidential election contest, Republicans secured Tennessean Andrew Johnson as a new vice presidential candidate to make inroads with disaffected Democrats and project a united front to Northerners. Hamlin reported to active military duty and trained at Fort McClary in Maine. After his training concluded, he campaigned mightily for the Lincoln-Johnson ticket, and after Lincoln’s assassination raced back to Washington to stand aside Andrew Johnson at Lincoln’s funeral. Hamlin returned to the Senate in 1868, where he served two more terms. In 1881 he was appointed minister to Spain for two years, then retired from public life and died while playing cards in 1891.

Edward Everett’s soaring oratory, Joseph Lane’s unflinching proslavery rhetoric, Herschel Johnson’s insistent unionism, and Hannibal Hamlin’s triumph of principles over party, revealed a country in conflict and made the election of 1860 the most pivotal election in American history. Four parties stood counterpoised over a yawning precipice that in a few short months would echo with gunfire. As the above snapshots show, the vice presidential candidates who shared the ticket were not merely tagalongs: they were purposeful, political men, impassioned yet desperate to bring about a future most beneficial to their interpretation of America’s purpose.

This post was also featured on RealClear History.

Elliott Drago serves as the JMC’s Editorial Officer. He is a historian of American history and the author of Street Diplomacy: The Politics of Slavery and Freedom in Philadelphia, 1820-1850 (Johns-Hopkins University Press, 2022).