Article I, Section 2, Clause 5 of the Constitution gives the House of Representatives “sole Power of Impeachment.” On September 24, 2019, Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi announced the beginning of an impeachment inquiry against President Donald Trump. Below we have collected primary sources related to impeachment and work by JMC fellows and faculty partners on impeachment from a Constitutional and historical point of view.

On October 28, 2019, the Center for American Studies at Christopher Newport University, a JMC partner program, held its 13th Annual Conference on America’s Founding Principles and History. This year’s theme was “Scandal and Impeachment: From the Founding to the Present” and featured JMC faculty partners Keith Whittington, who delivered the keynote address, “A Formidable Weapon of Faction? The Law and Politics of Impeachment,” and Joseph Knippenberg.

“A Formidable Weapon of Faction? The Law and Politics of Impeachment”

Keith Whittington

Below is a collection of resources on impeachment. Browse these resources or jump from section to section by clicking the links below:

The Impeachment Clauses of the Constitution

From The Founders’ Constitution:

Article 1, Section 2, Clause 5

The House of Representatives shall chuse their Speaker and other Officers; and shall have the sole Power of Impeachment.

Article 1, Section 3, Clauses 6 and 7

The Senate shall have the sole Power to try all Impeachments. When sitting for that Purpose, they shall be on Oath or Affirmation. When the President of the United States is tried the Chief Justice shall preside; And no Person shall be convicted without the Concurrence of two thirds of the Members present.

Judgement in Cases of Impreachment shall not extend further than to removal from Office, and disqualification to hold and enjoy any Office of honor, Trust or Profit under the United States: but the Party convicted shall nevertheless be liable and subject to Indictment, Trial, Judgement and Punishment, according to Law.

Article 2, Section 4

The President, Vice President and all Civil Officers of the United States, shall be removed from Office on Impeachment for, and Conviction of, Treason, Bribery, or other high Crimes and Misdemeanors.

Federalist 65

To the People of the State of New York:

THE remaining powers which the plan of the convention allots to the Senate, in a distinct capacity, are comprised in their participation with the executive in the appointment to offices, and in their judicial character as a court for the trial of impeachments. As in the business of appointments the executive will be the principal agent, the provisions relating to it will most properly be discussed in the examination of that department. We will, therefore, conclude this head with a view of the judicial character of the Senate.

A well-constituted court for the trial of impeachments is an object not more to be desired than difficult to be obtained in a government wholly elective. The subjects of its jurisdiction are those offenses which proceed from the misconduct of public men, or, in other words, from the abuse or violation of some public trust. They are of a nature which may with peculiar propriety be denominated POLITICAL, as they relate chiefly to injuries done immediately to the society itself. The prosecution of them, for this reason, will seldom fail to agitate the passions of the whole community, and to divide it into parties more or less friendly or inimical to the accused. In many cases it will connect itself with the pre-existing factions, and will enlist all their animosities, partialities, influence, and interest on one side or on the other; and in such cases there will always be the greatest danger that the decision will be regulated more by the comparative strength of parties, than by the real demonstrations of innocence or guilt.

The delicacy and magnitude of a trust which so deeply concerns the political reputation and existence of every man engaged in the administration of public affairs, speak for themselves. The difficulty of placing it rightly, in a government resting entirely on the basis of periodical elections, will as readily be perceived, when it is considered that the most conspicuous characters in it will, from that circumstance, be too often the leaders or the tools of the most cunning or the most numerous faction, and on this account, can hardly be expected to possess the requisite neutrality towards those whose conduct may be the subject of scrutiny.

The convention, it appears, thought the Senate the most fit depositary of this important trust. Those who can best discern the intrinsic difficulty of the thing, will be least hasty in condemning that opinion, and will be most inclined to allow due weight to the arguments which may be supposed to have produced it.

What, it may be asked, is the true spirit of the institution itself? Is it not designed as a method of NATIONAL INQUEST into the conduct of public men? If this be the design of it, who can so properly be the inquisitors for the nation as the representatives of the nation themselves? It is not disputed that the power of originating the inquiry, or, in other words, of preferring the impeachment, ought to be lodged in the hands of one branch of the legislative body. Will not the reasons which indicate the propriety of this arrangement strongly plead for an admission of the other branch of that body to a share of the inquiry? The model from which the idea of this institution has been borrowed, pointed out that course to the convention. In Great Britain it is the province of the House of Commons to prefer the impeachment, and of the House of Lords to decide upon it. Several of the State constitutions have followed the example. As well the latter, as the former, seem to have regarded the practice of impeachments as a bridle in the hands of the legislative body upon the executive servants of the government. Is not this the true light in which it ought to be regarded?

Where else than in the Senate could have been found a tribunal sufficiently dignified, or sufficiently independent? What other body would be likely to feel CONFIDENCE ENOUGH IN ITS OWN SITUATION, to preserve, unawed and uninfluenced, the necessary impartiality between an INDIVIDUAL accused, and the REPRESENTATIVES OF THE PEOPLE, HIS ACCUSERS?

Could the Supreme Court have been relied upon as answering this description? It is much to be doubted, whether the members of that tribunal would at all times be endowed with so eminent a portion of fortitude, as would be called for in the execution of so difficult a task; and it is still more to be doubted, whether they would possess the degree of credit and authority, which might, on certain occasions, be indispensable towards reconciling the people to a decision that should happen to clash with an accusation brought by their immediate representatives. A deficiency in the first, would be fatal to the accused; in the last, dangerous to the public tranquillity. The hazard in both these respects, could only be avoided, if at all, by rendering that tribunal more numerous than would consist with a reasonable attention to economy. The necessity of a numerous court for the trial of impeachments, is equally dictated by the nature of the proceeding. This can never be tied down by such strict rules, either in the delineation of the offense by the prosecutors, or in the construction of it by the judges, as in common cases serve to limit the discretion of courts in favor of personal security. There will be no jury to stand between the judges who are to pronounce the sentence of the law, and the party who is to receive or suffer it. The awful discretion which a court of impeachments must necessarily have, to doom to honor or to infamy the most confidential and the most distinguished characters of the community, forbids the commitment of the trust to a small number of persons.

These considerations seem alone sufficient to authorize a conclusion, that the Supreme Court would have been an improper substitute for the Senate, as a court of impeachments. There remains a further consideration, which will not a little strengthen this conclusion. It is this: The punishment which may be the consequence of conviction upon impeachment, is not to terminate the chastisement of the offender. After having been sentenced to a perpetual ostracism from the esteem and confidence, and honors and emoluments of his country, he will still be liable to prosecution and punishment in the ordinary course of law. Would it be proper that the persons who had disposed of his fame, and his most valuable rights as a citizen in one trial, should, in another trial, for the same offense, be also the disposers of his life and his fortune? Would there not be the greatest reason to apprehend, that error, in the first sentence, would be the parent of error in the second sentence? That the strong bias of one decision would be apt to overrule the influence of any new lights which might be brought to vary the complexion of another decision? Those who know anything of human nature, will not hesitate to answer these questions in the affirmative; and will be at no loss to perceive, that by making the same persons judges in both cases, those who might happen to be the objects of prosecution would, in a great measure, be deprived of the double security intended them by a double trial. The loss of life and estate would often be virtually included in a sentence which, in its terms, imported nothing more than dismission from a present, and disqualification for a future, office. It may be said, that the intervention of a jury, in the second instance, would obviate the danger. But juries are frequently influenced by the opinions of judges. They are sometimes induced to find special verdicts, which refer the main question to the decision of the court. Who would be willing to stake his life and his estate upon the verdict of a jury acting under the auspices of judges who had predetermined his guilt?

Would it have been an improvement of the plan, to have united the Supreme Court with the Senate, in the formation of the court of impeachments? This union would certainly have been attended with several advantages; but would they not have been overbalanced by the signal disadvantage, already stated, arising from the agency of the same judges in the double prosecution to which the offender would be liable? To a certain extent, the benefits of that union will be obtained from making the chief justice of the Supreme Court the president of the court of impeachments, as is proposed to be done in the plan of the convention; while the inconveniences of an entire incorporation of the former into the latter will be substantially avoided. This was perhaps the prudent mean. I forbear to remark upon the additional pretext for clamor against the judiciary, which so considerable an augmentation of its authority would have afforded.

Would it have been desirable to have composed the court for the trial of impeachments, of persons wholly distinct from the other departments of the government? There are weighty arguments, as well against, as in favor of, such a plan. To some minds it will not appear a trivial objection, that it could tend to increase the complexity of the political machine, and to add a new spring to the government, the utility of which would at best be questionable. But an objection which will not be thought by any unworthy of attention, is this: a court formed upon such a plan, would either be attended with a heavy expense, or might in practice be subject to a variety of casualties and inconveniences. It must either consist of permanent officers, stationary at the seat of government, and of course entitled to fixed and regular stipends, or of certain officers of the State governments to be called upon whenever an impeachment was actually depending. It will not be easy to imagine any third mode materially different, which could rationally be proposed. As the court, for reasons already given, ought to be numerous, the first scheme will be reprobated by every man who can compare the extent of the public wants with the means of supplying them. The second will be espoused with caution by those who will seriously consider the difficulty of collecting men dispersed over the whole Union; the injury to the innocent, from the procrastinated determination of the charges which might be brought against them; the advantage to the guilty, from the opportunities which delay would afford to intrigue and corruption; and in some cases the detriment to the State, from the prolonged inaction of men whose firm and faithful execution of their duty might have exposed them to the persecution of an intemperate or designing majority in the House of Representatives. Though this latter supposition may seem harsh, and might not be likely often to be verified, yet it ought not to be forgotten that the demon of faction will, at certain seasons, extend his sceptre over all numerous bodies of men.

But though one or the other of the substitutes which have been examined, or some other that might be devised, should be thought preferable to the plan in this respect, reported by the convention, it will not follow that the Constitution ought for this reason to be rejected. If mankind were to resolve to agree in no institution of government, until every part of it had been adjusted to the most exact standard of perfection, society would soon become a general scene of anarchy, and the world a desert. Where is the standard of perfection to be found? Who will undertake to unite the discordant opinions of a whole community, in the same judgment of it; and to prevail upon one conceited projector to renounce his INFALLIBLE criterion for the FALLIBLE criterion of his more CONCEITED NEIGHBOR? To answer the purpose of the adversaries of the Constitution, they ought to prove, not merely that particular provisions in it are not the best which might have been imagined, but that the plan upon the whole is bad and pernicious.

PUBLIUS.

Other Primary Resources from The Founders’ Constitution:

The Founders’ Constitution, edited by Philip B. Kurland and JMC faculty partner Ralph Lerner. Also available online at the University of Chicago.

Jefferson’s Manual of Parliamentary Practice for the Use of the Senate of the United States

Jefferson’s Manual of Parliamentary Practice for the Use of the Senate of the United States

As Vice President (and President of the Senate) Thomas Jefferson collected a manual of parliamentary procedure to be used by the Senate. The final sections describes how impeachment was practiced in England.

Discussion of Impeachment at the Constitutional Convention

Discussion of Impeachment at the Constitutional Convention

Gouverneur Morris (July 18, 1787):

The Executive is also to be impeachable. This is a dangerous part of the plan. It will hold him in such dependence that he will be no check on the Legislature, will not be a firm guardian of the people and of the public interest. He will be the tool of a faction, of some leading demagogue in the Legislature. These then are the faults of the Executive establishment as now proposed. Can no better establishmt. be devised? If he is to be the Guardian of the people let him be appointed by the people? If he is to be a check on the Legislature let him not be impeachable. Let him be of short duration, that he may with propriety be re-eligible…

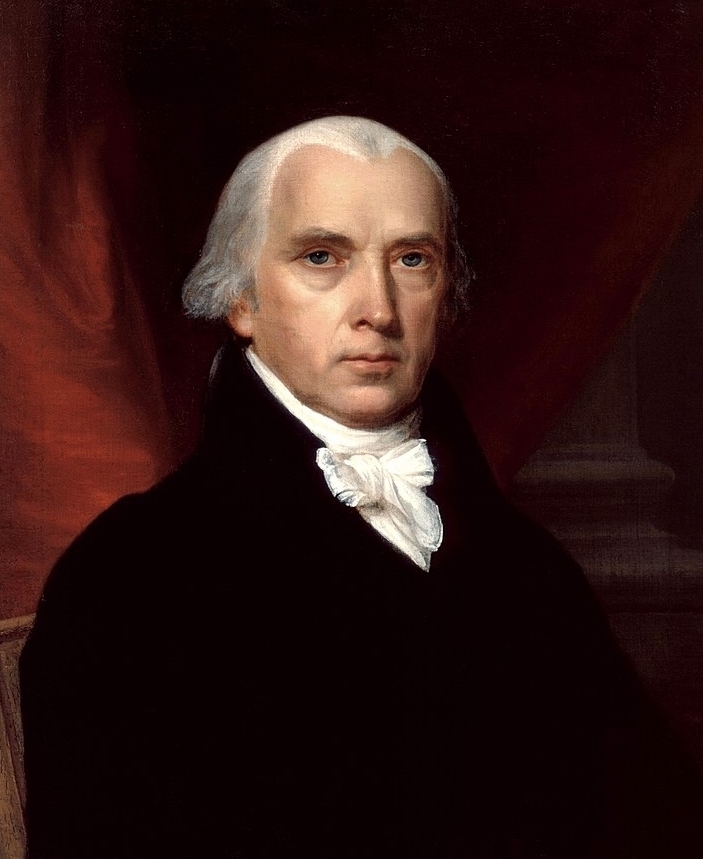

James Madison (July 20, 1787):

James Madison (July 20, 1787):

Mr. Madison–thought it indispensable that some provision should be made for defending the Community agst the incapacity, negligence or perfidy of the chief Magistrate. The limitation of the period of his service, was not a sufficient security. He might lose his capacity after his appointment. He might pervert his administration into a scheme of peculation or oppression. He might betray his trust to foreign powers. The case of the Executive Magistracy was very distinguishable, from that of the Legislative or of any other public body, holding offices of limited duration. It could not be presumed that all or even a majority of the members of an Assembly would either lose their capacity for discharging, or be bribed to betray, their trust. Besides the restraints of their personal integrity & honor, the difficulty of acting in concert for purposes of corruption was a security to the public. And if one or a few members only should be seduced, the soundness of the remaining members, would maintain the integrity and fidelity of the body. In the case of the Executive Magistracy which was to be administered by a single man, loss of capacity or corruption was more within the compass of probable events, and either of them might be fatal to the Republic.

Read More Discussion of Impeachment from the Convention >>

Antifederalist Views on Impeachment

Antifederalist Views on Impeachment

Luther Martin, A Genuine Information (1788):

It was further observed, that the only appearance of responsibility in the President, which the system holds up to our view, is the provision for impeachment; but that when we reflect that he cannot be impeached but by the house of delegates, and that the members of this house are rendered dependant upon, and unduly under the influence of the President, by being appointable to offices of which he has the sole nomination, so that without his favour and approbation, they cannot obtain them, there is little reason to believe, that a majority will ever concur in impeaching the President, let his conduct be ever so reprehensible, especially too, as the final event of that impeachment will depend upon a different body, and the members of the house of delegates will be certain, should the decision be ultimately in favour of the President, to become thereby the objects of his displeasure, and to bar to themselves every avenue to the emoluments of government…

Brutus, No. 15 (20 Mar. 1788):

The only clause in the constitution which provides for the removal of the judges from office, is that which declares, that “the president, vice-president, and all civil officers of the United States, shall be removed from office, on impeachment for, and conviction of treason, bribery, or other high crimes and misdemeanors.” By this paragraph, civil officers, in which the judges are included, are removable only for crimes. Treason and bribery are named, and the rest are included under the general terms of high crimes and misdemeanors.–Errors in judgment, or want of capacity to discharge the duties of the office, can never be supposed to be included in these words, high crimes and misdemeanors. A man may mistake a case in giving judgment, or manifest that he is incompetent to the discharge of the duties of a judge, and yet give no evidence of corruption or want of integrity. To support the charge, it will be necessary to give in evidence some facts that will shew, that the judges commited the error from wicked and corrupt motives…

Read more impeachment clauses from The Founders’ Constitution >>

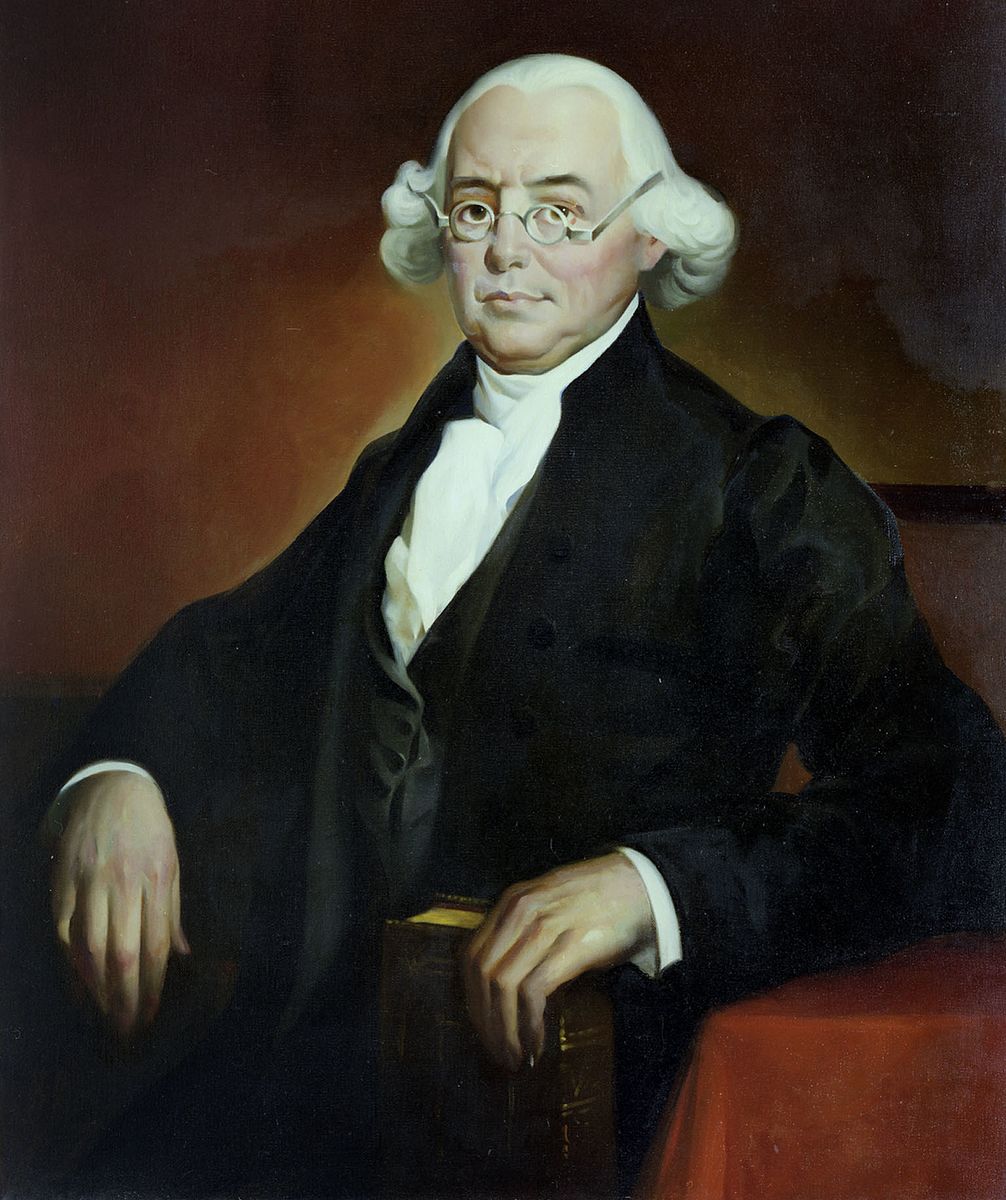

James Wilson, Legislative Department, Lectures on Law

James Wilson, Legislative Department, Lectures on Law

The doctrine of impeachments is of high import in the constitutions of free states. On one hand, the most powerful magistrates should be amenable to the law: on the other hand, elevated characters should not be sacrificed merely on account of their elevation. No one should be secure while he violates the constitution and the laws: every one should be secure while he observes them…

Joseph Story, Commentaries on the Constitution

Joseph Story, Commentaries on the Constitution

In England the constitutional maxim is, that the king can do no wrong. His ministers and advisers may be impeached and punished; but he is, by his prerogative, placed above all personal amenability to the laws for his acts. In some of the state constitutions, no explicit provision is made for the impeachment of the chief magistrate; and in Delaware and Virginia, he was not (under their old constitutions) impeachable, until he was out of office. So that no immediate remedy in those states was provided for gross malversations and corruptions in office; and the only redress lay in the elective power, followed up by prosecutions after the party had ceased to hold his office. Yet cases may be imagined, where a momentary delusion might induce a majority of the people to re-elect a corrupt chief magistrate; and thus the remedy would be at once distant and uncertain. The provision in the constitution of the United States, on the other hand, holds out a deep and immediate responsibility, as a check upon arbitrary power; and compels the chief magistrate, as well as the humblest citizen, to bend to the majesty of the laws…

Articles of Impeachment: A Timeline

Andrew Johnson (1868)

Andrew Johnson (1868)

During President Andrew Johnson’s impeachment proceedings, the Senate claimed that he had unlawfully removed Secretary of War Edwin Stanton. Johnson was not successfully convicted.

Read the Johnson articles of impeachment at Teaching American History >>

Richard Nixon (1974)

Richard Nixon (1974)

Unlike Johnson, President Richard Nixon resigned before formal impeachment could take place. During the Watergate Scandal, it was revealed that had obstructed the administration of justice.

Read the Nixon articles of impeachment at Watergate.info >>

William Clinton (1998)

William Clinton (1998)

President Bill Clinton was impeached under the charges of lying under oath and obstruction of justice after the Lewinsky Affair. Like Andrew Johnson, he was acquitted after trial in the Senate.

Commentary and articles from JMC fellows:

Impeachment and American Political Development

Jeremy Bailey, “Constitutionalism, Conflict, and Consent: Jefferson on the Impeachment Power.” (Review of Politics 70.4, Fall 2008)

John Dearborn and Jack Greenberg, “Impeachment and American Political Development.” (A House Divided, October 11, 2019)

Stephen Presser, “Impeachment.” (The Dictionary of American History, Charles Scribner’s Sons, 2003)

Stephen Presser, “Impeachment.” (The Dictionary of American History, Charles Scribner’s Sons, 2003)

Stephen Presser, “Impeachment Trial of Samuel Chase.” (The Oxford Companion to American Law, Oxford University Press, 2002)

Stephen Presser, “The Verdict on Samuel Chase and His ‘Apologist.’” (Seriatim: The Supreme Court, Before John Marshall, New York University Press, 1998)

Jeffrey Tulis, “Impeachment in the Constitutional Order.” (The Constitutional Presidency, Johns Hopkins University Press, 2009)

Keith Whittington, “A Formidable Weapon of Faction? The Law and Politics of Impeachment” (Law and Social Inquiry, Forthcoming)

Keith Whittington, “Reconstructing the Federal Judiciary: The Chase Impeachment and the Constitution.” (Studies in American Political Development 9.1, May 30, 1995)

The Contemporary Politics of Impeachment

John Dearborn, “Impeaching the President: Some Perspective from the Archives.” (A House Divided, October 4, 2019)

Andrew Lewis, “Roger Stone says there would be an ‘insurrection’ if Trump were impeached. Is he right?” (Washington Post, September 15, 2017)

Stephen Presser, “There is No Good Case for Impeachment.” (American Greatness, November 26, 2019)

Stephen Presser, “Democrats Preposterous Impeachment Aims Endanger Republic.” (Newsmax, November 5, 2019)

Stephen Presser, “A Trump Impeachment Imperils the Constitution.” (Newsmax, October 21, 2019)

Stephen Presser, “Would George Washington have wanted Bill Clinton impeached?” (George Washington Law Review 67, 1999)

George Thomas, “Donald Trump, Constitutional Ignoramus.” (The Bulwark, October 16, 2019)

Gregory Weiner, “Continue the Investigation. Begin the Impeachment.” (The Bulwark, October 15, 2019)

Gregory Weiner, “Continue the Investigation. Begin the Impeachment.” (The Bulwark, October 15, 2019)

Gregory Weiner, “Trump Has Overplayed His Hand.” (New York Times, September 26, 2019)

Gregory Weiner, “An Impotent Congress Can’t Impeach Trump.” (Law & Liberty, April 25, 2019)

Gregory Weiner, “How Not to Impeach.” (New York Times, January 1, 2018)

Gregory Weiner, “Impeachment’s Political Heart.” (New York Times, May 18, 2017)

Keith Whittingon, “Must Impeachable Offenses Be Violations of the Criminal Code?” (Lawfare, November 19, 2019)

Keith Whittington, “Trump’s Defiance Is Destroying Congress’s Power.” (The Atlantic, October 14, 2019)

Keith Whittington, “Trump is creating the worst constitutional crisis in 150 years.” (Los Angeles Times, October 10, 2019)

Keith Whittington, “Congress has the legal tools to make the White House cooperate.” (Vox, October 9, 2019)

Keith Whittington, “Must the House Vote to Authorize an Impeachment Inquiry?” (Lawfare, October 9, 2019)

Keith Whittington, “And Then the President Asked to be Impeached.” (The Volokh Conspiracy, October 8, 2019)

Keith Whittingon, “Impeachment isn’t mandatory — even if Trump committed impeachable offenses” (Washington Post, September 26, 2019)

Keith Whittington, “Is a Senate Impeachment Trial Optional?” (Niskanen Center, September 25, 2019)

Keith Whittington, “Resolved, the Presidential Impeachment Process is Basically Sound.” (Debating the Presidency: Conflicting Perspectives on the American Executive, CQ Press, 2006)

Keith Whittington, “Bill Clinton was no Andrew Johnson: Comparing Two Impeachments.” (University of Pennsylvania Journal of Constitutional Law 2.2, Spring 2000)

*If you are a JMC fellow who’s published on the impeachment process, its history, or its contemporary use, and would like your work included here, send it to us at academics@gojmc.org.

![]()

![]() Follow us on Facebook and Twitter for updates about lectures, publications, podcasts, and events related to American political thought, United States history, and the Western tradition!

Follow us on Facebook and Twitter for updates about lectures, publications, podcasts, and events related to American political thought, United States history, and the Western tradition!

Want to help the Jack Miller Center transform higher education? Donate today.

Joseph Story, Commentaries on the Constitution

Joseph Story, Commentaries on the Constitution