Free Speech Week: Celebrating a Crucial First Amendment Right

This year, Free Speech Week falls on the week of October 21-27. Freedom of speech and freedom of the press are some of the important constitutionally-protected rights that citizens hold. Without the protection of these rights, critical thought and the communication of ideas become nearly impossible. In the Western canon, figures such as John Milton, John Locke, and William Blackstone wrote extensively on liberty, speech, and the law. By the time of the American founding, a uniquely American view of freedom of speech and the press had been established.

As early as the 1730s, the American colonists were contradicting British common law in the trial of John Peter Zenger, showing a strong commitment to the protection of truthful speech. Zenger was arrested in 1733 for publishing The New York Weekly Journal, a newspaper that was consistently critical of the colonial governor of New York. Zenger’s counsel argued, contrary to the common law standard of seditious libel, that the truth of his newspaper’s claims should be considered as grounds for his defense. Despite the colonial judge’s firm instructions to the jury that their duty was to decide only whether he had in fact published the essays in question, the jury acquitted Zenger in a bold act of “jury nullification.”

As early as the 1730s, the American colonists were contradicting British common law in the trial of John Peter Zenger, showing a strong commitment to the protection of truthful speech. Zenger was arrested in 1733 for publishing The New York Weekly Journal, a newspaper that was consistently critical of the colonial governor of New York. Zenger’s counsel argued, contrary to the common law standard of seditious libel, that the truth of his newspaper’s claims should be considered as grounds for his defense. Despite the colonial judge’s firm instructions to the jury that their duty was to decide only whether he had in fact published the essays in question, the jury acquitted Zenger in a bold act of “jury nullification.”

The American zeal for freedom of expression influenced the founders’ decision to include freedom of speech and freedom of the press in the first amendment of the Bill of Rights. Since the founding, free speech has remained controversial, particularly during times of war or, more recently, in the context of the college campus. The introduction of the internet and social media have added further complication to how and when citizens express their right to speech.

Free Speech Week is an annual nonpartisan holiday that takes place during the third week of October and celebrates freedom of speech and freedom of the press. Free Speech Week was created in 2005 by the Media Institute and the National Association of Broadcaster’s Education Foundation as “National Freedom of Speech Week.” Since then, Free Speech Week has become independent of any organization, though the Media Institute still maintains the official website. The unofficial designation, though fairly recent and neither state nor federal in origin, is significant nonetheless: Free Speech Week encourages individuals, educators, and organizations to raise awareness of the history and value of free speech.

In recognition of Free Speech Week, the Jack Miller Center offers a wide array of scholarly resources on free speech, its history, its controversies, and its important role in the press and higher education. Please take a moment this week to explore our First Amendment Library and to reflect on some of our most important constitutional rights.

JMC’s First Amendment Library:

The Jack Miller Center’s website has a treasure trove of resources on freedom of speech. The JMC First Amendment Library includes sections on the history, law, and theory behind freedom of speech. Learn about the most fundamental origins of the right to free speech, the American view of it, and controversies that have arisen in the past 232 years.

The Free Speech History section provides a historical timeline of free speech. Browse primary documents and resources that span hundreds of years, from Socratic political philosophy, to the American founding, to controversial U.S. government leaks of recent years.

The Free Speech History section provides a historical timeline of free speech. Browse primary documents and resources that span hundreds of years, from Socratic political philosophy, to the American founding, to controversial U.S. government leaks of recent years.

Explore the History of Free Speech >>

The Free Speech Law section traces the development of American laws pertaining to freedom of speech. Beginning with the original founding documents, this section of the library touches on the legal complications of sedition, offensive speech, and libel and defamation.

The Free Speech Law section traces the development of American laws pertaining to freedom of speech. Beginning with the original founding documents, this section of the library touches on the legal complications of sedition, offensive speech, and libel and defamation.

Explore U.S. Law on Free Speech >>

The Free Speech Theory section provides an overview of free speech’s role in political theory and scholarly thought. Our library includes the political theory of Aristotle, John Milton, and John Locke, who influenced the American founders, as well as several contemporary theorists, including Stanley Fish and Catherine MacKinnon.

The Free Speech Theory section provides an overview of free speech’s role in political theory and scholarly thought. Our library includes the political theory of Aristotle, John Milton, and John Locke, who influenced the American founders, as well as several contemporary theorists, including Stanley Fish and Catherine MacKinnon.

Explore the Theory of Free Speech >>

Founding Documents

Declarations of Independence and Rights

Declarations of Independence and Rights

When the tension between the colonists and the British crown came to a head with a violent confrontation between British soldiers and the Massachusetts militia in April of 1775, American leaders from the thirteen colonies convened a Continental Congress to organize an army to fight for their independence. In July of the following year, this Congress issued a declaration of the colonies’ independence from Great Britain. This declaration justified the colonies’ rebellion by stating “self-evident” “truths” about the purpose and foundation of government and by explaining how the British government had consistently failed to meet the standards of those truths. This articulation of a classical liberal conception of government, based on equality and natural rights, would serve as the moral foundation of the United States’ Constitution.

The Continental Congress’s Declaration of Independence was not, however, the only public defense of the states’ break with the crown; nor was it the only public statement of their political principles. Individual states issued their own declarations of rights and of independence, both as stand-alone resolutions and as parts of new state constitutions. The most famous of these is the Virginia Declaration of Rights, which preceded the Continental Declaration by nearly a month. The Virginia Declaration departs from earlier documents in its articulation of the purpose of government as a protector of natural rights. Its language is recognizable both in the national Declaration of Independence in subsequent declarations and constitutions of other states.

Read more about the Declarations in our First Amendment Library >>

The Original Constitution

The Original Constitution

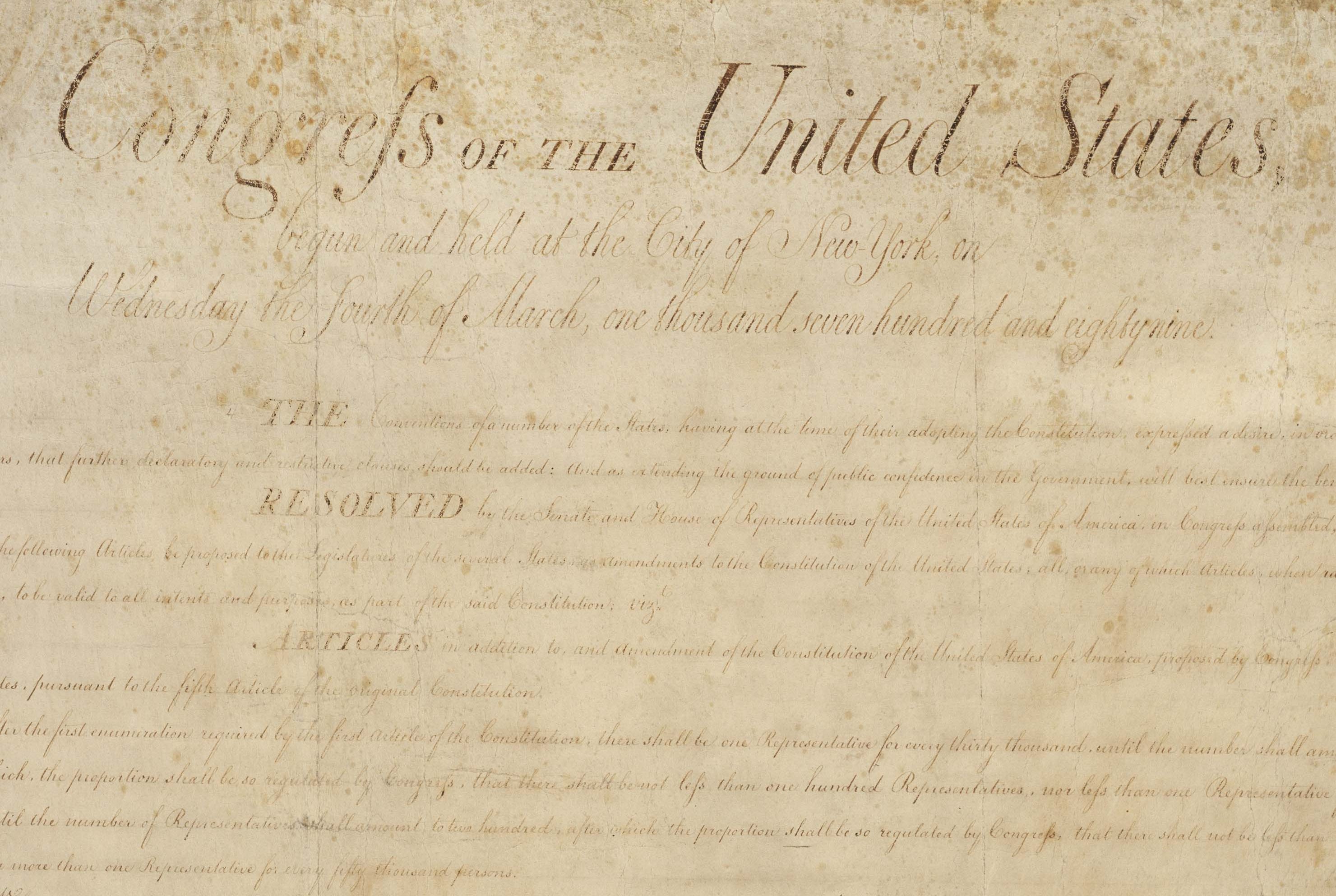

The original Constitution of the United States proposed for ratification by the Federal Convention of 1787 lacked any explicit reference to freedom of speech or of the press. According to the Federalist Framers of the Constitution, explicit provisions for such freedoms as speech and the press were unnecessary, since the Constitution granted only certain narrow powers to Congress. They argued that by including a Bill of Rights, which seemed to imply such a Bill was necessary, the Constitution might taken as implying that the Congress had more power than it did. Despite this argument, the absence of a Bill of Rights was incredibly unpopular and nearly cost it its ratification.

Read more about the original Constitution in our First Amendment library >>

Passage of the Bill of Rights

Passage of the Bill of Rights

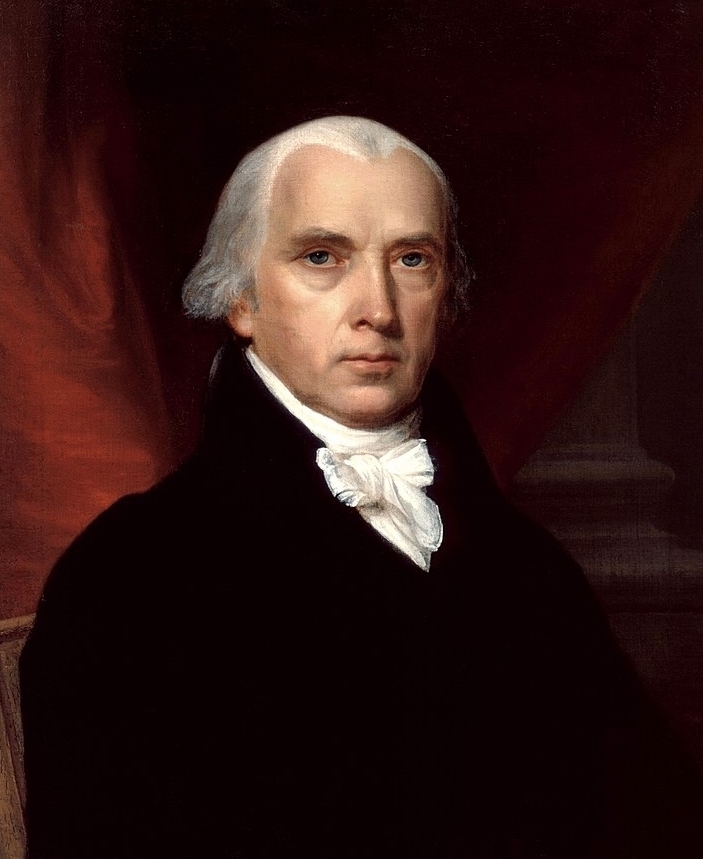

Only a month after the Constitution was printed and distributed, the first ratifying convention took place in Pennsylvania. The ratification process went relatively smoothly for a couple months after that, with five state conventions approving ratification with little difficulty. In January of 1788, however, the ratifying convention in Massachusetts devolved into a bitter and even violent deadlock, largely over the question of a bill of rights. Only by promising to introduce a Bill of Rights as amendments were the Federalist supporters of the Constitution able to break the deadlock and secure ratification in Massachusetts. Without this strategy, which was subsequently adopted in other states with Federalist minorities, the Constitution could not have been ratified. Despite the reservations of many of the Federalists, who had a commanding majority in the first Congress, James Madison recognized the necessity of keeping their promise and adding a Bill of Rights quickly in order to secure the legitimacy of the new government. He submitted a proposal for seventeen amendments based on the Virginia Declaration of rights early in 1789. This proposal went through four stages of rigorous debate and revision in the House and the Senate before being approved by Congress in September of 1789. Of the twelve articles in the approved amendments, ten were ratified as by the states over the course of the next two years, becoming what is now known as our Bill of Rights. The first of these ten included the provision that “Congress shall make no law … abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press.”

Read more about the Bill of Rights in our First Amendment Library >>

Commentary and articles from JMC fellows:

Freedom of Speech: Controversies and Complications

Jonathan Bean, “Abortion and Free Speech.” (FreeU, October 21, 2008)

Jonathan Bean, “Abortion and Free Speech.” (FreeU, October 21, 2008)

Nicholas Capaldi (translator), Clear and Present Danger, The Free Speech Controversy. (Bobbs-Merrill, 1970)

Andrew Lewis, “Freedom of Religion and Freedom of Speech: The Effects of Alternative Rights Frames on Mass Support for Public Exemptions.” (Journal of Church and State 60.1, 2018)

Andrew Lewis, “Learning the Value of Rights: Abortion Politics and the Liberalization of Evangelical Free Speech Advocacy.” (Politics & Religion 9.2, 2016)

Arthur Milikh, “Rethinking the Bill of Rights.” (National Review, December 15, 2016)

Michael Munger, “Locking Up Political Speech: How Electioneering Communications Laws Stifle Free Speech and Civic Engagement.” (Institute for Justice, 2009)

Laura Beth Nielsen, License to Harass: Law, Hierarchy, and Offensive Public Speech. (Princeton University Press, 2004)

Laura Beth Nielsen, “Power in Public: Reactions, Responses, and Resistance to Offensive Public Speech.” (Speech and Harm: Controversies Over Free Speech, Oxford University Press, 2012)

Laura Beth Nielsen, “Power in Public: Reactions, Responses, and Resistance to Offensive Public Speech.” (Speech and Harm: Controversies Over Free Speech, Oxford University Press, 2012)

Stephen Presser, “Between Free Speech and the Flag.” (American Legion Magazine 155, July 2003)

Stephen Presser, “Reasons We Shouldn’t Be Here: Things we Cannot Say.” (Unsettling Sensation: Arts Policy Lessons from the Brooklyn Museum Controversy, Rutgers University Press, 2001)

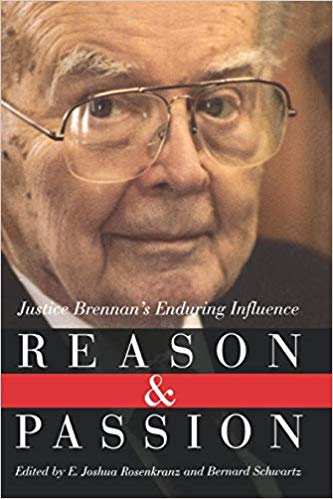

Jeffrey Rosen, “We Hardly Know it When we See it: Obscenity and the Problem of Unprotected Speech.” (Reason and Passion: Justice Brennan’s Enduring Influence, Norton, 1997)

Kevin Wagner, “Adderley v. Florida: Restricting Protests on Public Property.” (The Encyclopedia of Civil Liberties in America, Routledge, 2004)

Thomas West, “Free Speech in the American Founding and in Modern Liberalism.” (Social Philosophy and Policy 21.2, July 15, 2004)

Thomas West, “Free Speech in the American Founding and in Modern Liberalism.” (Social Philosophy and Policy 21.2, July 15, 2004)

Jonathan White, “‘Words Become Things’: Free Speech in Civil War Pennsylvania.” (Pennsylvania Legacies 8, 2008)

Scott Yenor, “Hate Crimes: Protected Prejudice or Punishable Motive?” (Moral Controversies in American Politics, M.E. Sharpe, 2004)

Michael Zuckert, “Constitutionalism in the Age of Terror.” (Social Philosophy and Policy, December 15, 2011)

Freedom of the Press

Bryan Garsten, “The ‘spirit of independence’ in Benjamin Constant’s thoughts on a free press.” (Censorship Moments: Reading Texts in the History of Censorship and Freedom of Expression, Bloomsbury Academic, 2015)

Bryan Garsten, “The ‘spirit of independence’ in Benjamin Constant’s thoughts on a free press.” (Censorship Moments: Reading Texts in the History of Censorship and Freedom of Expression, Bloomsbury Academic, 2015)

Arthur Milikh, “Franklin and the Free Press.” (National Affairs, March 1, 2017)

Jeffrey Pasley, “Popular Constitutionalism in Philadelphia: How Freedom of Expression was Secured by Two Fearless Newspaper Editors.” (Pennsylvania Legacies 8, 2008)

Jeffrey Pasley, “Thomas Greenleaf: Printers and the Struggle for Democratic Politics and Freedom of the Press.” (Revolutionary Founders: Rebels, Radicals, and Reformers in the Making of the Nation, Alfred A. Knopf, 2011)

Freedom of Speech on Campus

Jonathan Bean, “Big Brother and U, Part I: Is Your University Reading Your Email?” (FreeU, January 24, 2009)

Jonathan Bean, “Big Brother and U, Part II: Is Your University Reading Your Email?” (FreeU, January 31, 2009)

Jonathan Bean, “Big Brother and U, Part II: Is Your University Reading Your Email?” (FreeU, January 31, 2009)

Michael Munger, “Free to Hate? Free Speech on American University Campuses.” (Independent Review 24.2, 2019)

Vincent Phillip Muñoz,

Keith Whittington, “Free Speech and Ideological Diversity on American College Campuses.” (The Value and Limits of Academic Free Speech: Philosophical, Political, and Legal Perspectives, Routledge Press, 2018)

Keith Whittington, Speak Freely: Why Universities Must Defend Free Speech. (Princeton University Press, 2018)

Freedom of Speech and the Internet

Jeffrey Rosen, “The Deciders: The Future of Privacy and Free Speech in the Age of Facebook and Google.” (Fordham Law Review 80.4, 2012)

Jeffrey Rosen, “The Deciders: The Future of Privacy and Free Speech in the Age of Facebook and Google.” (Fordham Law Review 80.4, 2012)

Jeffrey Rosen, “Free Speech, Privacy, and the Web that Never Forgets.” (Journal on Telecommunications & High Technology Law 9, 2011)

Kevin Wagner, “Internet Freedom and Social Media Effects: Democracy and Citizen Attitudes in Latin America.” (Online Information Review 40.5, 2016)

Commercial Speech

Stephen Presser, “Commercial Speech and the First Amendment: Cigarette Companies and the Playboy Channel Have Rights Too–Or Do They?” (Chronicles: A Magazine of American Culture, October 2000)

Stephen Presser, “Commercial Speech and the First Amendment: Cigarette Companies and the Playboy Channel Have Rights Too–Or Do They?” (Chronicles: A Magazine of American Culture, October 2000)

Kevin Wagner, “City of Cincinnati v. Discovery Network: Constitutional Protections for Commercial Speech.” (The Encyclopedia of the First Amendment, 2008)

Keith Whittington, “A Note on Commercial Speech in the Era of Late Capitalism.” (The Good Society: A PEGS Journal 14.2, 2005)

*If you are a JMC fellow who’s published on freedom of speech, the First Amendment, or their histories and controversies, and would like your work included here, send it to us at academics@gojmc.org.

Pivotal Free Speech Supreme Court Cases

People v. Croswell (1804)

Despite their complaints over the Federalists’ use of the Alien and Sedition Acts to prosecute the opposition, Republicans did not hesitate to prosecute Federalist opposition for libel at the state level once they won the presidency with the election of Thomas Jefferson in 1800. Croswell published a small paper called The Wasp, which aggressively criticized Thomas Jefferson and other Republican public officials. When he was a arrested and convicted on charges of libel and sedition by the State of New York, Croswell appealed to the Supreme Court of New York, where he was defended by Alexander Hamilton and James Kent. Though the judges were evenly split and the conviction stood, the case gave a high-profile occasional for Hamilton and Kent to make a case for permitting truth as a defense against libel charges.

Despite their complaints over the Federalists’ use of the Alien and Sedition Acts to prosecute the opposition, Republicans did not hesitate to prosecute Federalist opposition for libel at the state level once they won the presidency with the election of Thomas Jefferson in 1800. Croswell published a small paper called The Wasp, which aggressively criticized Thomas Jefferson and other Republican public officials. When he was a arrested and convicted on charges of libel and sedition by the State of New York, Croswell appealed to the Supreme Court of New York, where he was defended by Alexander Hamilton and James Kent. Though the judges were evenly split and the conviction stood, the case gave a high-profile occasional for Hamilton and Kent to make a case for permitting truth as a defense against libel charges.

Read more in the First Amendment library >>

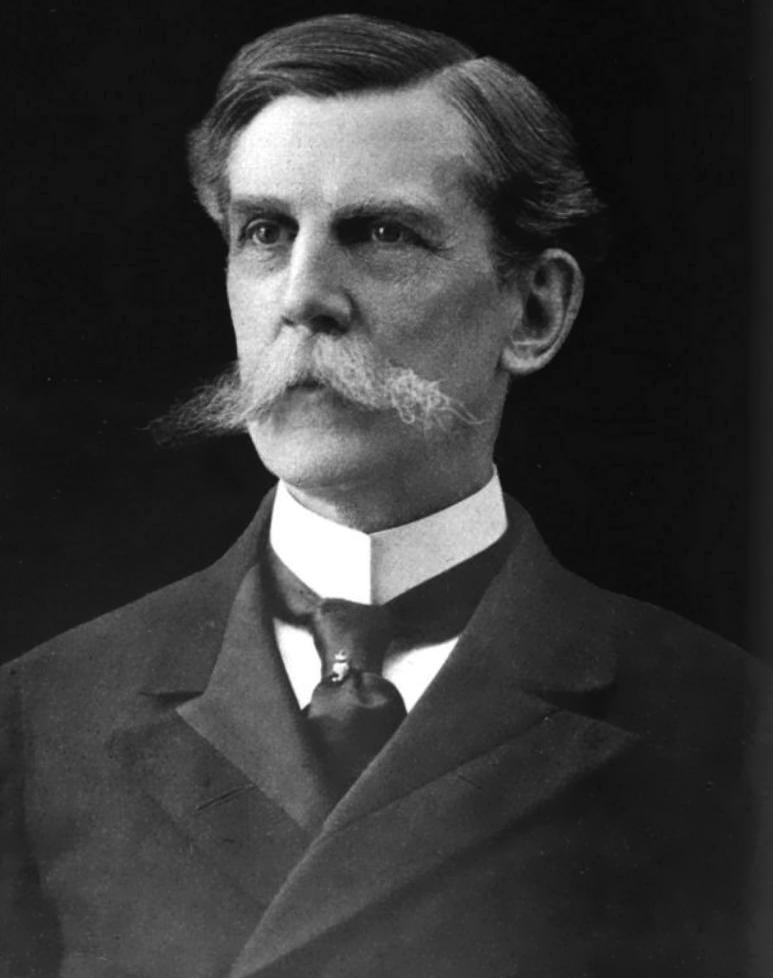

Schenck v. United States (1919)

Schenck v. United States (1919)

More resources for Free Speech Week:

The Origins of Free Speech Week

The Origins of Free Speech Week

The official Free Speech Week website offers numerous resources, lesson plans, free speech quotes, and activity ideas. Its purpose is to raise public awareness of the importance of freedom of speech and of a free press in the United States – and to celebrate that freedom. The non-partisan, non-ideological event is intended to be a unifying celebration.

Visit the official Free Speech Week website >>

The Library of Congress Web Guide to the Bill of Rights

The Library of Congress Web Guide to the Bill of Rights

The Library of Congress offers a a digital collection of primary sources tracking the development and passage of the Bill of Rights. The collection includes selections from the papers of Washington, Jefferson, and Madison, as well as newspapers of the time.

Explore the Library of Congress Web Guide >>

The National Constitution Center’s Interactive Constitution

The National Constitution Center’s Interactive Constitution

The National Constitution Center offers a collection of introductory essays by top liberal and conservative legal scholars that give overviews of each amendment clause as agreed upon by both authors, as well as separate brief statements of these scholars’ disagreements about the meaning of each clause. For the First Amendment, the NCC offers analysis from Geoffrey Stone and Eugene Volokh.

Read the NCC’s free speech essays here >>

The Heritage Guide to the Constitution

The Heritage Guide to the Constitution

The Heritage Foundation’s Guide to the Constitution includes scholarly essays on each component of the First Amendment, including freedom of speech and of the press.

Visit the Heritage Guide to the Constitution >>

Free Speech on College Campuses: Where Should Universities Draw the Line?

Free Speech on College Campuses: Where Should Universities Draw the Line?

In March 2019, the National Constitution Center held a series of panels in which professors, administrators, and student advocates discussed and debated freedom of speech on campus. Panelists included Amy Wax, Anita Bernstein, and Tom Sullivan. The panels were recorded and are available on the NCC website.

Watch the discussions at the National Constitution Center website >>

*If you are a JMC fellow who’s published on freedom of speech, the First Amendment, or their histories and controversies, and would like your work included here, send it to us at academics@gojmc.org.

![]()

![]() Follow us on Facebook and Twitter for updates about lectures, publications, podcasts, and events related to American political thought, United States history, and the Western tradition!

Follow us on Facebook and Twitter for updates about lectures, publications, podcasts, and events related to American political thought, United States history, and the Western tradition!

Want to help the Jack Miller Center transform higher education? Donate today.

Declarations of Independence and Rights

Declarations of Independence and Rights

Schenck v. United States (1919)

Schenck v. United States (1919) Doe v. University of Michigan (1989)

Doe v. University of Michigan (1989)