Independence Day has only been a federal holiday since 1941, but July 4th has been celebrated as our country’s birthday since the eighteenth century. Fittingly, the first celebration took place in Philadelphia, site of the Declaration of Independence and home of the Jack Miller Center, in 1776, mere days after the Declaration was signed. The celebration continued as an annual event in Philadelphia and soon became widespread in the new nation.

Celebratory activities have not changed much since the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries – like our forefathers, we read the Declaration aloud, hold parades, and shoot off fireworks. Here in Philadelphia, we symbolically tap the Liberty Bell thirteen times each year to remember the hard-won success of the original thirteen colonies.

In recognition of Independence Day, the Jack Miller Center presents the following collection of resources about the Declaration of Independence, its history and its political and theoretical legacy. A number of JMC fellows have written about this document’s importance and the ways in which it has contributed to our nation’s political identity.

Below is a collection of resources exploring the Declaration of Independence, its history, and its political and theoretical legacy. Browse these resources or jump from section to section by clicking the links below:

From JMC’s First Amendment Library:

Declarations of Independence and Rights

Declarations of Independence and Rights

When the tension between the colonists and the British crown came to a head with a violent confrontation between British soldiers and the Massachusetts militia in April of 1775, American leaders from the thirteen colonies convened a Continental Congress to organize an army to fight for their independence. In July of the following year, this Congress issued a declaration of the colonies’ independence from Great Britain. This declaration justified the colonies’ rebellion by stating “self-evident” “truths” about the purpose and foundation of government and by explaining how the British government had consistently failed to meet the standards of those truths. This articulation of a classical liberal conception of government, based on equality and natural rights, would serve as the moral foundation of the United States’ Constitution.

Read more about the Declaration in our First Amendment Library >>

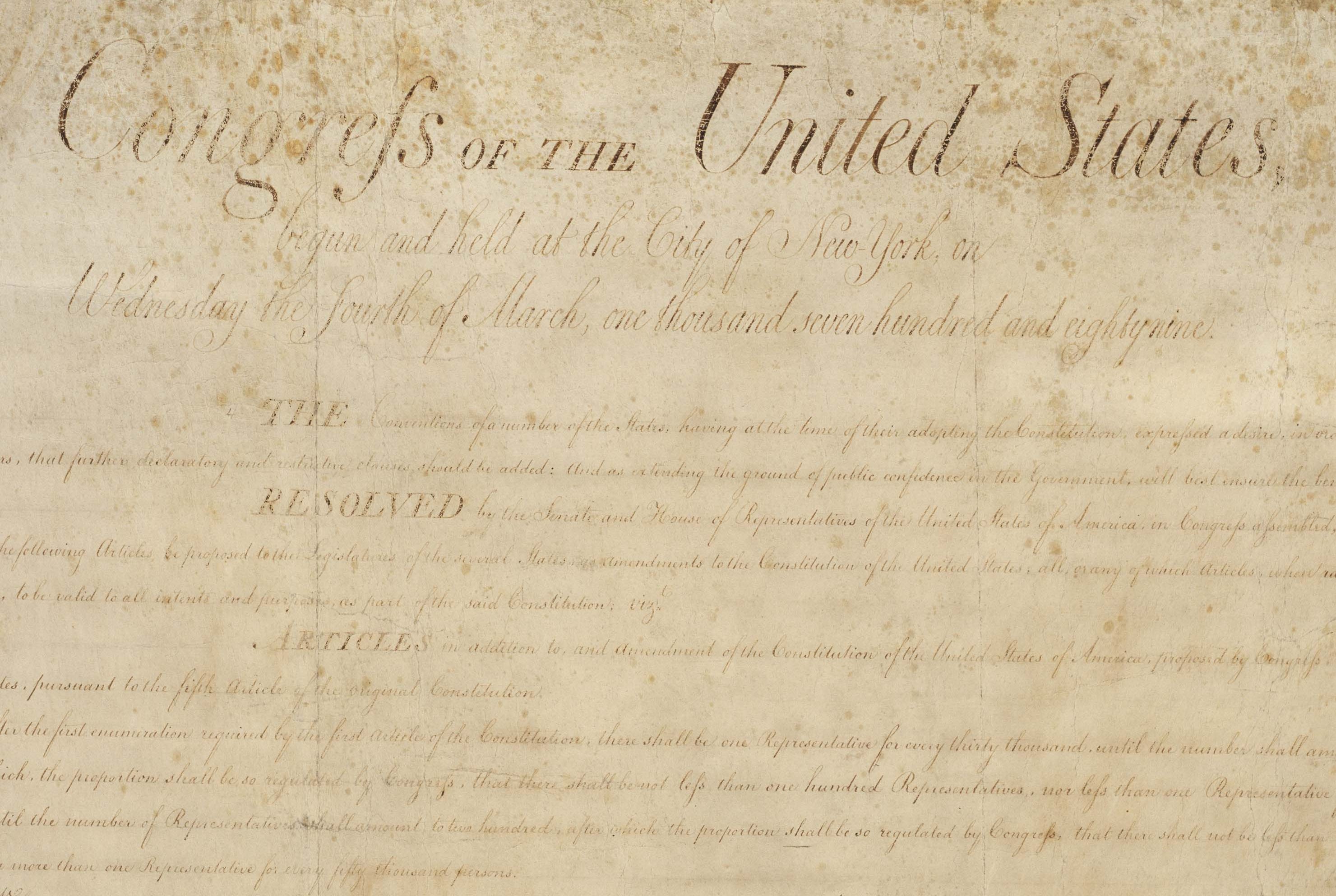

The Original Constitution

The Original Constitution

The original Constitution of the United States proposed for ratification by the Federal Convention of 1787 lacked any explicit reference to freedom of speech or of the press. According to the Federalist Framers of the Constitution, explicit provisions for such freedoms as speech and the press were unnecessary, since the Constitution granted only certain narrow powers to Congress. They argued that by including a Bill of Rights, which seemed to imply such a Bill was necessary, the Constitution might taken as implying that the Congress had more power than it did. Despite this argument, the absence of a Bill of Rights was incredibly unpopular and nearly cost it its ratification.

Read more about the original Constitution in our First Amendment library >>

Passage of the Bill of Rights

Passage of the Bill of Rights

Only a month after the Constitution was printed and distributed, the first ratifying convention took place in Pennsylvania. The ratification process went relatively smoothly for a couple months after that, with five state conventions approving ratification with little difficulty. In January of 1788, however, the ratifying convention in Massachusetts devolved into a bitter and even violent deadlock, largely over the question of a bill of rights. Only by promising to introduce a Bill of Rights as amendments were the Federalist supporters of the Constitution able to break the deadlock and secure ratification in Massachusetts. Without this strategy, which was subsequently adopted in other states with Federalist minorities, the Constitution could not have been ratified. Despite the reservations of many of the Federalists, who had a commanding majority in the first Congress, James Madison recognized the necessity of keeping their promise and adding a Bill of Rights quickly in order to secure the legitimacy of the new government. He submitted a proposal for seventeen amendments based on the Virginia Declaration of rights early in 1789. This proposal went through four stages of rigorous debate and revision in the House and the Senate before being approved by Congress in September of 1789. Of the twelve articles in the approved amendments, ten were ratified as by the states over the course of the next two years, becoming what is now known as our Bill of Rights. The first of these ten included the provision that “Congress shall make no law … abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press.”

Read more about the Bill of Rights in our First Amendment Library >>

Selected online resources on the Declaration of Independence:

JMC Video Series on the Declaration of Independence

JMC Video Series on the Declaration of Independence

What did the Founders mean by equality? Did they understand it differently than we do? Who among history’s great political thinkers influenced those who authored the Declaration? And how might the Founders shed light on our own concerns with equality today? We put these and other questions to the nation’s leading scholars of American political thought.

What So Proudly We Hail

What So Proudly We Hail

The What So Proudly We Hail online curriculum offers an ebook,“The Meaning of Independence Day,” that explores the ideas behind the American Founding and their significance for our present personal freedoms and national flourishing. The ebook contains over 50 selections, from colonial times to the present, chosen and arranged to illuminate a series of themes: declaring, securing, and maintaining independence; the promise of the new republic; seeking a more perfect union (with special attention to securing equal rights for African Americans and women); and celebrating the holiday and remembering its national promise. Each selection includes a brief introduction by the editors with guiding questions for discussion.

July 4th at the National Archives

July 4th at the National Archives

Explore the history of Independence Day and “sign” the Declaration yourself at the National Archives, the home of the Declaration of Independence, Constitution, and Bill of Rights.

Visit the National Archives website >>

The Digital Declaration of Independence

The Digital Declaration of Independence

This interactive Declaration of Independence combines a high-resolution scan of the 1823 facsimile with a full-text transcription of the text, an annotated version of John Trumbull’s 1819 painting of the signing of the document, and an interactive map that plots the signers’ hometowns.

Explore the Digital Declaration of Independence >>

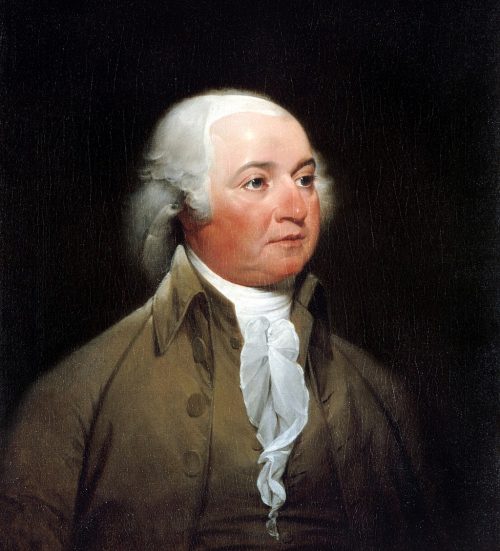

John Adams’s Vision of July 4 was July 2?

John Adams’s Vision of July 4 was July 2?

John Adams believed July 2 would be “the most memorable Epocha, in the History of America.” The National Archives provides insight into Adams’s dreams for our national holiday and why he believed that we would celebrate it on July 2.

Read John Adams’s thoughts on Independence Day at the National Archives >>

*If you are a JMC fellow who’s published on the Declaration of Independence, Independence Day, or their histories and controversies, and would like your work included here, send it to us at academics@gojmc.org.

Commentary and articles from JMC fellows:

Happiness in the Declaration

Carli Conklin, The Pursuit of Happiness in the Founding Era: An Intellectual History. (University of Missouri Press, 2019)

Carli Conklin, The Pursuit of Happiness in the Founding Era: An Intellectual History. (University of Missouri Press, 2019)

Jonathan Culp, “Justice, Happiness, and the Sensible Knave: Hume’s Incomplete Defense of the Just Life.” (Review of Politics 75.2, Spring 2013)

Michael Gillespie, “The Tragedy of the Goods and the Pursuit of Happiness.” (In Search of Goodness, University of Chicago Press, 2011)

Christopher Kelly, “Rousseau on the Pursuit of Happiness.” (Rousseau and Dignity: Art Serving Humanity, Notre Dame University Press, 2017)

Scott Yenor, “Humanity and Happiness: Philosophic Treatment of Happiness in a Non-Teleological World.” (Interpretation: A Journal of Political Philosophy 31.3, Summer 2004)

History of the Declaration and Revolution

Bernard Bailyn, The Ideological Origins of the American Revolution. (Harvard University Press, 1967)

Bernard Bailyn, The Ideological Origins of the American Revolution. (Harvard University Press, 1967)

Seth Cotlar, “Tom Paine’s Readers and the Making of Democratic Citizens in the Age of Revolutions.” (Thomas Paine: Common Sense for the Modern Era, San Diego State University Press, 2007)

Ioannis Evrigenis, “A Founder on Founding: Jefferson’s Advice to Koraes.” (The Historical Review I, 2004)

Robert Faulkner, The Life of George Washington. (Liberty Fund Press, 2000)

Bryan Garsten, “The ‘spirit of independence’ in Benjamin Constant’s thoughts on a free press.” (Censorship Moments: Reading Texts in the History of Censorship and Freedom of Expression, Bloomsbury Academic, 2015)

Eliga Gould, “American Independence and Britain’s Counter-Revolution.” (Past & Present 154.1, February 1997)

Eliga Gould, “Independence and Interdependence: The American Revolution and the Problem of Post-Colonial Nationhood, circa 1802.” (William and Mary Quarterly 74.4, October 2017)

Eliga Gould, “Liberty and Modernity: The American Revolution and the Parliamentary History of the British Empire.” (Exclusionary Empire: British Libertarian Traditions in the Construction of the British Settler Empire, Cambridge University Press, 2009)

Eliga Gould, The Persistence of Empire: British Political Culture in the Age of the American Revolution. (University of North Carolina Press, 2000)

Eliga Gould, “A Virtual Nation: Greater Britain and the Imperial Legacy of the American Revolution.” (American Historical Review 104, 1999)

James F. Hrdlicka. “‘The Attachment of the People’: The Massachusetts Charter, the French and Indian War, and the Coming of the American Revolution.” (The New England Quarterly 89.3, 2016)

Mark David Hall (editor), America’s Forgotten Founders. (ISI Books, 2012)

Benjamin Irvin, “Independence before and during the Revolution.” (Oxford Handbook of the American Revolution, Oxford University Press, 2015)

Benjamin Irvin, “The Second Continental Congress.” (Reporting the Revolutionary War, Sourcebooks, 2012)

Benjamin Irvin, “The Second Continental Congress.” (Reporting the Revolutionary War, Sourcebooks, 2012)

Benjamin Irvin, “The Streets of Philadelphia: Crowds, Congress, and the Political Culture of Revolution, 1774-1783.” (Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 129.1, 2005)

Charles Kesler, “A Special Meaning of the Declaration of Independence.” (National Review 31.27, July 6, 1979)

John Gilbert McCurdy, Quarters: The Accommodation of the British Army and the Coming of the American Revolution. (Cornell University Press, 2019)

Eric Nelson, The Royalist Revolution: Monarchy and the American Founding. (Harvard/Belknap, 2014)

Eric Nelson, “What kind of book is The Ideological Origins of the American Revolution?” (The New England Quarterly 91, 2018)

Peter Onuf (editor), Declaring Independence: The Origin and Influence of America’s Founding Document. (University of Virginia Library, 2008)

Lorraine Pangle, “George Washington and the Life of Honor.” (The Noblest Minds: Fame, Honor, and the American Founding, Rowman and Littlefield, 1999)

Benjamin E. Park, American Nationalisms: Imagining Union in the Age of Revolutions, 1783-1833. (Cambridge University Press, 2018)

John A. Ragosta, Wellspring of Liberty: How Virginia’s Religious Dissenters Helped Win the American Revolution & Secured Religious Liberty. (Oxford University Press, 2010)

Mark Somos, American States of Nature: The Origins of Independence, 1761-1775 (Oxford University Press, 2019)

Mark Somos, American States of Nature: The Origins of Independence, 1761-1775 (Oxford University Press, 2019)

Patrick Spero (editor), The American Revolution Reborn. (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2016)

Patrick Spero, “The Other Theater: The War for American Independence beyond the Colonies.” (History Now 34, Winter 2012)

J. Logan Tomlin, “Reluctant Among Revolutionaries: Sectarian Politics and Conscription in Revolutionary Pennsylvania, 1775-1778.” (Phi Alpha Theta Regional Journal, 2011)

Andrew Trees, “Understanding the Story of Benedict Arnold, John Andre, and the Three Yeoman Captors: American Virtue Defined.” (Early American Literature 35.3, 2000)

Thomas West, “The Declaration of Independence, the U.S. Constitution, and the Bill of Rights.” (The Declaration of Independence: Origins and Impact, CQ Press, 2002)

The Declaration and Constitutional Law

Mark David Hall, “The Declaration of Independence in the Supreme Court.” (The Declaration of Independence: Origins and Impact, Congressional Quarterly Press, 2002)

Mark David Hall, “The Declaration of Independence in the Supreme Court.” (The Declaration of Independence: Origins and Impact, Congressional Quarterly Press, 2002)

James Stoner, “The Common Law Spirit of the American Revolution.” (Educating the Prince: Essays in Honor of Harvey Mansfield, Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2000)

Thomas West,

Justin Dyer (editor), American Soul: The Contested Legacy of the Declaration of Independence. (Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2012)

The Political Theory of the Declaration of Independence

Jeremy Bailey, “Nature and Nature’s God in the Notes on the State of Virginia.” (Enlightenment and Secularism: Essays on the Mobilization of Reason, Lexington Books, 2013)

Jeremy Bailey, “Nature and Nature’s God in the Notes on the State of Virginia.” (Enlightenment and Secularism: Essays on the Mobilization of Reason, Lexington Books, 2013)

Justin Dyer, “Thomas Jefferson, Nature’s God, and the Theological Foundations of Natural-Rights Republicanism.” (Politics & Religion 10.3, 2017)

Robert Faulkner, “Jefferson and the Enlightened Science of Liberty.” (Reason and Republicanism: Thomas Jefferson’s Legacy of Liberty, Rowman & Littlefield, 1997)

Thomas Merrill, “The Later Jefferson and the Problem of Natural Rights.” (Perspectives on Political Science 44.2, 2015)

James Ashley Morrison, “Before Hegemony: Adam Smith, American Independence, and the Origins of the First Era of Globalization.” (International Organization 66.3, Summer 2012)

S. Adam Seagrave, “Darwin and the Declaration.” (Politics and the Life Sciences 30.1, Spring 2011)

Rogers Smith, “Lockean Liberalism and American Constitutionalism in the Twenty-First Century: The Declaration of Independence or ‘America First’?” (American Political Thought 8.2, Spring 2019)

Rogers Smith, “The Politics of Rights, Then and Now.” (The Nature of Rights at the American Founding and Beyond, University of Virginia Press, 2007)

James Stoner, “Is There a Political Philosophy in the Declaration of Independence?” (Intercollegiate Review 40.2, Fall/Winter 2005)

Thomas West, “Jaffa versus Mansfield: Does America Have a Constitutional or a ‘Declaration of Independence’ Soul?“ (Perspectives on Political Science 31.4, Fall 2002)

Thomas West, “The Political Theory of the Declaration of Independence.” (The American Founding and the Social Compact, Lexington Books, 2003)

Jean Yarbrough, “Race and the Moral Foundation of the American Republic: Another Look at the Declaration and the Notes on Virginia.” (The Journal of Politics 53.1, 1991)

Michael Zuckert, The Natural Rights Republic: Studies in the Foundation of the American Political Tradition. (University of Notre Dame Press, 1997)

Michael Zuckert, “Self-Evident Truth and the Declaration of Independence.” (The Review of Politics 49.3, Summer 1987)

Michael Zuckert, “Thomas Jefferson and Natural Morality: Classical Moral Theory, Moral Sense, and Rights.” (Thomas Jefferson, the Classical World, and Early America, University of Virginia Press, 2011)

Michael Zuckert, “Thomas Jefferson on Nature and Natural Rights.” (The Framers and Fundamental Rights, AEI Press, 1992)

Thomas Jefferson and the Politics of Nature (essays in response to Michael Zuckert’s Natural Rights Republic). (University of Notre Dame Press, 2000)

Celebrating Independence Day

Shira Lurie, “Why Democrats are wrong about Trump’s politicization of the Fourth of July.” (Washington Post, July 3, 2019)

Shira Lurie, “Why Democrats are wrong about Trump’s politicization of the Fourth of July.” (Washington Post, July 3, 2019)

Benjamin E. Park, “Why do Mormons Love the Fourth of July So Much?” (Religion & Politics, 2012)

Andrew Trees, “Three Cheers for July Second.” (The Washington Post, July 2, 2008)

Kyle Volk, “What if the Fourth of July were dry?” (OUPblog, 2014)

*If you are a JMC fellow who’s published on the Declaration of Independence, Independence Day, or their histories and controversies, and would like your work included here, send it to us at academics@gojmc.org.

![]()

![]() Follow us on Facebook and Twitter for updates about lectures, publications, podcasts, and events related to American political thought, United States history, and the Western tradition!

Follow us on Facebook and Twitter for updates about lectures, publications, podcasts, and events related to American political thought, United States history, and the Western tradition!

Want to help the Jack Miller Center transform higher education? Donate today.